Atlas of memory: Gordon Ford’s natural Australian garden

With a career spanning six decades, Gordon Ford was a grand master of the Australian natural garden. Briony Downes looks at the key elements of his practice and how a new exhibition sheds light on his enduring legacy.

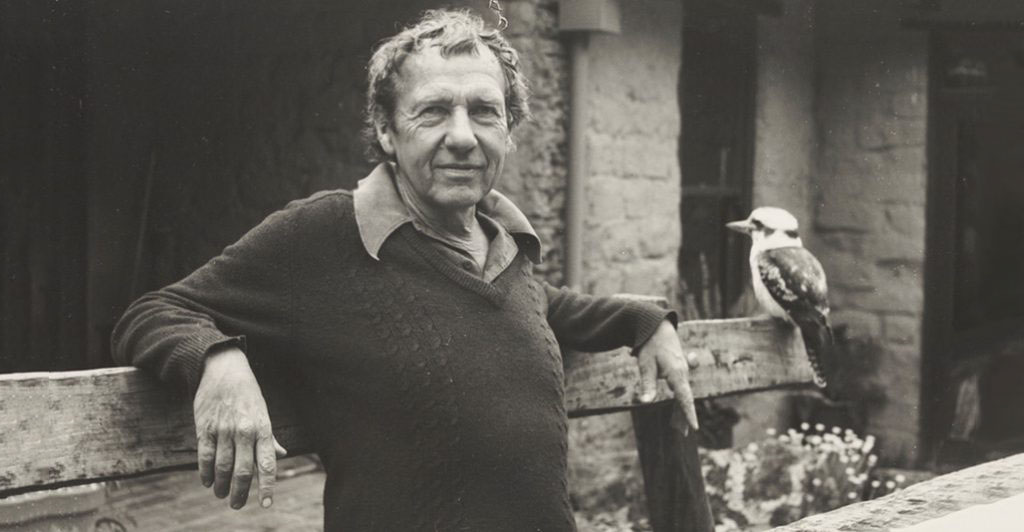

Australian landscape designer Gordon Ford was a practical, hands-on worker who has remained an elusive figure compared to many of his contemporaries. Trained in the early 1940s by Ellis Stones and working in Victoria at the same time as landscape designer Edna Walling and architect Alastair Knox, Ford was at the forefront of Australian bush-style gardening. Together, Stones, Walling and Ford each played a significant role in the Eltham creative movement in Victoria and while Ford remains a well-known figure in the landscaping industry, his dedication to the practical side of landscaping led to his many archival records rarely being seen in public.

To bring the wider context of Ford’s life and career into the spotlight, Annette Warner, a lecturer at the School of Ecosystems and Forest Sciences at the University of Melbourne, has spent five years collecting material relating to Ford’s practice for her PhD. The result is a comprehensive survey of Ford’s oeuvre drawn largely from his personal garden library and a detailed study of his garden, Fülling. Warner’s interviews with Ford’s friends, family and coworkers have revealed new insights into his work and alongside vintage photographs, newspaper clippings and garden journals, they form the basis of a companion exhibition, Atlas of Memory: (re)visualising Gordon Ford’s natural Australian garden, at the McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery.

“Chronologically, Ford’s work may be understood as an extension of the principles developed by Ellis Stones and Edna Walling in the post-World War Two period,” says Warner. “My opportunity to work on the Ford archive came about through a chance meeting with Ford’s last apprentice, landscape designer Sam Cox, just after Gwen Ford had passed away. I realised when I looked at Ford’s library and garden in Eltham, that this material would be important information to landscape and garden history in Australia.”

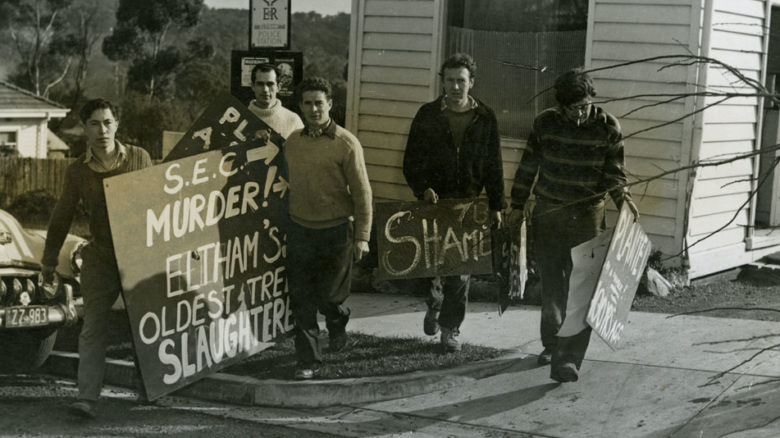

The legacy Ford left behind is enduring. Early in his career, Ford worked closely with Alastair Knox, a self-taught architect and landscape designer and together they worked alongside the artistic community of Montsalvat in the mid-1900s. Situated in Eltham, Montsalvat was originally developed by Justus Jörgensen and possessed a small cluster of houses made of mud brick – mud brick being used out of necessity when building materials became scarce after World War Two.

Since its inception, Montsalvat has attracted artists, musicians and writers, including painter Albert Tucker and artist Helen Lempriere, who carved many of the wooden and stone decorations. Montsalvat still retains a significant artistic community and continues to be an Australian landscape design landmark. Currently, both Montsalvat and Eltham are locations where new developments and subdivisions are restricted, maintaining the area’s status as a ‘green wedge’ suburb.

The pond at Gordon Ford's Fulling. Image: Annette Warner

Garden detail from Fulling. Image: Annette Warner

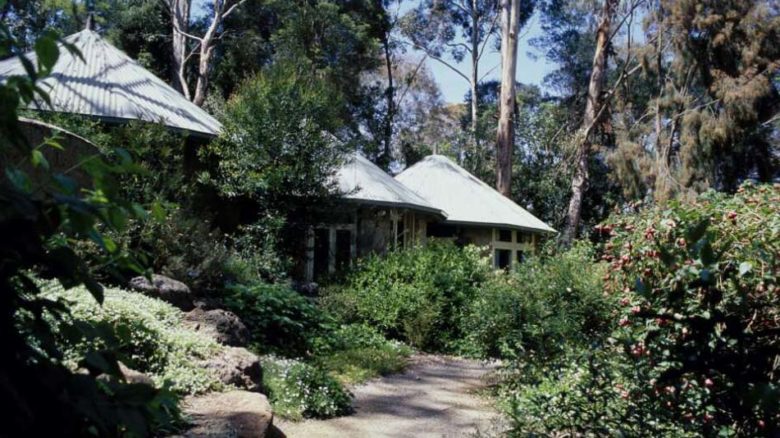

Fulling, Gwen and Gordon Ford's Eltham home. Image: Trisha Dixon, courtesy NLA

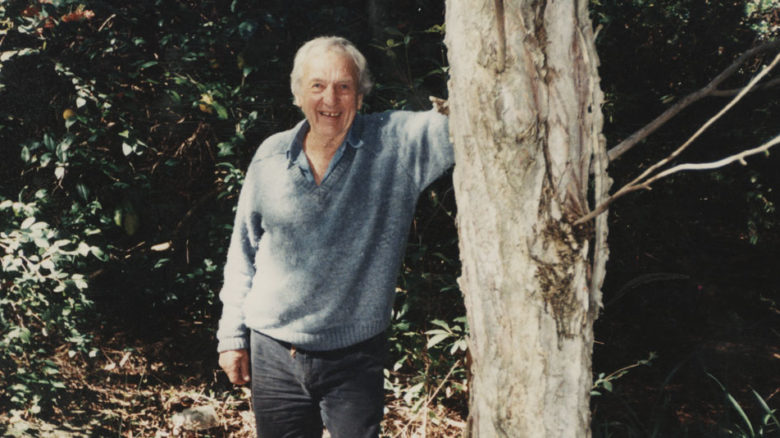

Encouraged by Knox and the community of Montsalvat, Ford built his own mud brick home in Eltham during the 1940s and over the succeeding decades, proceeded to grow and develop his extensive bush garden, Fülling. The mud brick house and its surrounding garden remained Ford’s home until his death in 1999 and serves as a living example of his natural garden style, with dense plantings of native ground cover giving way to towering eucalypts.

Initially inspired by rambling English gardens of the 18th century, Ford was known for his love of naturalism – the combination of stone, water and vegetation. Like Walling, Ford championed the use of native plants within naturalistic layers of rock and water. Through overlapping decades, Walling and Ford each worked in and around Eltham, slowly adding to a creatively enriched environment where many landscape elements still bear evidence of their craft.

The key elements of Ford’s favoured naturalistic style visually defined his gardens and there is a natural flow and continuity to his designs, with soft edges and undefined borders gently marked out by rambling pathways of loosely placed stepping stones. Native plants like Correa, Banksia and the bottlebrush dominated Ford’s Australian bush garden aesthetic, adding texture and colour while water features lent breathing space and a place to rest the eye. When Ford was alive, Fülling was one of the most popular locations in Eltham’s Open Garden Scheme weekends.

Montsalvat in Eltham has long been an important artist's hub. Image: Stephen Ridgway, Flickr cc

Franklin St Oaks protest 1952 (Ford second from right). Image: supplied

Gordon Ford in his garden at Fulling. Image: supplied by Annette Warner

To guide her research, Warner has used her own background as a horticulturist and landscape architect to couple archival objects from Ford’s collection with elements of text explaining their place within his practice. Like the title of the exhibition, she describes her PhD as an atlas of sorts, with the far-reaching research methods linking the trajectory of Ford’s practice together like points on a map. Influenced by the collecting methods of artist Gerhard Richter and art historian Aby Warburg, in Atlas of Memory Warner maps Ford’s career across the gallery space via a series of garden archives, each featuring items relating to a specific aspect of Ford’s gardens. Samples of plants from Fülling form the central pieces of these archives, along with black and white photographs and garden journals kept by Ford during the landscaping process.

Drawing from a career spanning six decades, in Ford’s library Warner inevitably discovered a rich array of material, including newspaper clippings from the 1950s onwards. One of these clippings features a quote by 18th century English poet Alexander Pope, favoured by Ford as a way to explain his creative mission to clients. Clearly relatable to Ford’s penchant for undefined borders in his garden designs, the quote reads, “He gains all ends/Who pleasingly confounds/Surprises, varies, and conceals/the bounds.” As Warner states, many of Ford’s clippings were undated and without reference to the publication, adding extra difficulty to the documentation process yet still offering a valuable insight into his style and career as a whole.

Throughout the research process, Warner also spent time with Ford’s friends and family, gathering personal stories and memories of his life and work. These associated recordings and filmed interviews have formed the collection of oral histories Warner has included in Atlas of Memory. “The acquisition of material was a long process that involved making contact and building relationships with key people who knew Ford. This resulted in an astonishingly diverse archive in its material media,” Warner explains. “This kind of research comes at a critical time when primary knowledge on the subject is at risk due to the age of those who were intimately involved in the milieu of which Ford was an active part.”

Warner extends the enduring scope of Ford’s legacy into the present day by also including the work of contemporary designers and artists in the exhibition. The video piece, ‘Voices Past and Present’ features a filmed interview with Cox, where he speaks of Ford’s influence on his own landscape design practice as well as the solid friendship they formed while working together. In addition to this video piece, garden design drawings by landscape architect Peter Glass and vintage photographs by filmmaker and artist, Sue Ford, further reveal how Ford’s distinctly Australian style still fits within contemporary design.

“To work on a collection such as this is something special because it points to the ideas behind Ford’s work and shows more of it by bringing the material forward to the present in what I hope is an interesting way,” Warner says.

As a dedicated landscape designer, Ford’s contribution to the development of the Australian bush garden is significant. With her research near completion, the value of research like Warner’s PhD project lies in its ability to chronologically document the path of Ford’s practice and add broader context to his diverse and varied career. Through Atlas of Memory, the scope of Ford’s legacy is presented to a wide audience via Warner’s evocative curation of archival records and the insights of those who knew him – from his friends, family and coworkers, right through to the contemporary designers still influenced by his methods and style today.

Atlas of Memory: (re)visualizing Gordon Ford’s Natural Australian Garden is on show at McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, 29 July – 11 November 2018

Briony Downes is an arts and design writer based in Hobart. She has worked in the arts industry for over 20 years as a writer, actor, gallery assistant, art theory tutor and fine art framer. Briony is currently a regular contributor to Art Guide Australia, Art Collector and Art Edit.