From an urban country to urban Country: Confronting the cult of denial in Australian cities

In this lecture from the 2017 State of Australian Cities conference, Libby Porter articulates how denial is embedded in Australian urban scholarship, and why we must acknowledge past wrongs if we are to open up “new possibilities for just and sustainable urban futures for all of us”.

Foreground advises that images of deceased Indigenous people are contained within this article.

The 2017 State of Australian Cities conference takes place on the unceded lands of the Kaurna people, who have practiced their sovereignty and law in this place for countless generations and who continue to care for this place. I pay respects to the Kaurna people, to their ancestors and old people, to their Elders present and future. I pay respects to Kaurna Country, which today and during this conference is going to hold us here and sustain us. I acknowledge the Wurundjeri and Bunurong peoples on whose Country I live and work, and also as my partners in much of the work that I do. To Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and Indigenous people from other parts of the world here today I pay my respects to you.

The words I’ve just said to acknowledge the place where we are and the unceded sovereignty of the people on whose Country we meet are not just words. Just like the welcome we were given this morning from our Kaurna hosts is not merely a hollow ritual – albeit one we experience fairly routinely now at the opening of major events like conferences or sporting matches – done because of some kind of political correctness. To interpret these important statements in this way misses their message. For if you listen carefully to that welcome you will hear what is in fact an invitation to be in a relationship, a right relationship, indeed a sovereign relationship, with Country and its people. The invitation is one of sharing this place, to become people of Country, even if in a different way than the first peoples of this country. I want to explore what this invitation means for thinking and building the city.

To do so requires exposing how our field of urban practice and scholarship in Australia continues to systematically turn its back on that invitation, and continues today to perpetuate not just a deafening silence but a cult of denial about the simple fact that all places in Australia, whether urban or otherwise, are Indigenous places. Always was always will be. And I use the term ‘our’ (in which I include myself) quite deliberately, as there are very few Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander urban scholars and practitioners in this country.

Statues of James Cook dot Australia, some with the incorrect inscription that he “discovered” Australia.

Image: State Archives NSW.

My take home message is, I hope, quite simple. It is this: our responsibility as scholars and practitioners of the urban is to shift our thinking and our practice to enable a consideration of the urban AS Country. And to do so not because this is vitally important for Indigenous justice, though that is of course urgent and important. But to do so because it is vital for ALL our shared urban futures. In other words, my talk today is not an appeal that we be nicer to Indigenous people, or that each of you include more ‘Indigeneity’ in your work. Those things might perhaps be fine (though not always, as this can inculcate a very problematic politics of inclusion, but I don’t have time for that here today)… but that’s not my point. Instead, I’m asking you to imagine how our field of urban scholarship and practice has been held back – is being held back – by an inability to accurately recognise and admit to the foundational story of Australian cities and to consider how seeing the urban-as-Country opens up new possibilities for just and sustainable urban futures for all of us.

Urban scholarship, theory and education in Australia remains mostly blind and deaf to the basic fact that all urban centres large and small are, and have always been, Aboriginal places, are already and are still Country. While we often talk about ourselves as an ‘urban country’ – wherein most of us live in towns and cities, a now global urban population phenomenon, as we know – we have been as yet unwilling and unable to grasp that this urban country is also urban Country.

Instead, what we have in urban practice and scholarship in Australia is what can only be called a structure of denial. This denial is built into the DNA of the contemporary Australian psyche. It is a cult of forgetfulness, as WEH Stanner identified in 1968 and that willing forgetfulness is a deliberate and required feature of the settler-colonial dynamic. Denial is the strategy settler (white, non-Indigenous) Australia mobilises in the face of what Tony Birch has called its “epic secret”: the intolerable injustice that unchecked settler-colonialism continues to wreak on this continent.

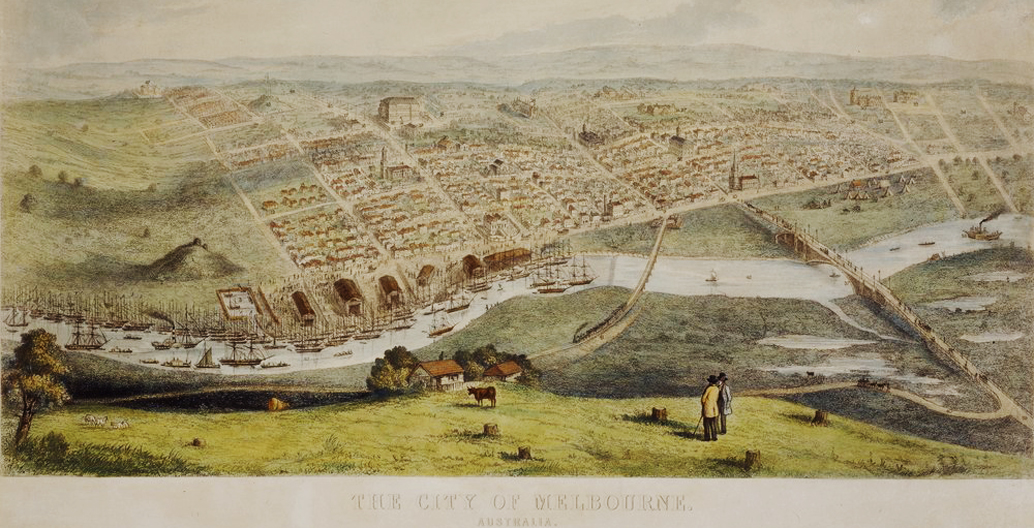

As a consequence we describe the early foundations of Australian cities incorrectly, as if the laying out of towns and cities like Colonel William Light’s grid here in Adelaide or Robert Hoddle’s in Melbourne was a process of heroic achievement rather than of theft and violence.

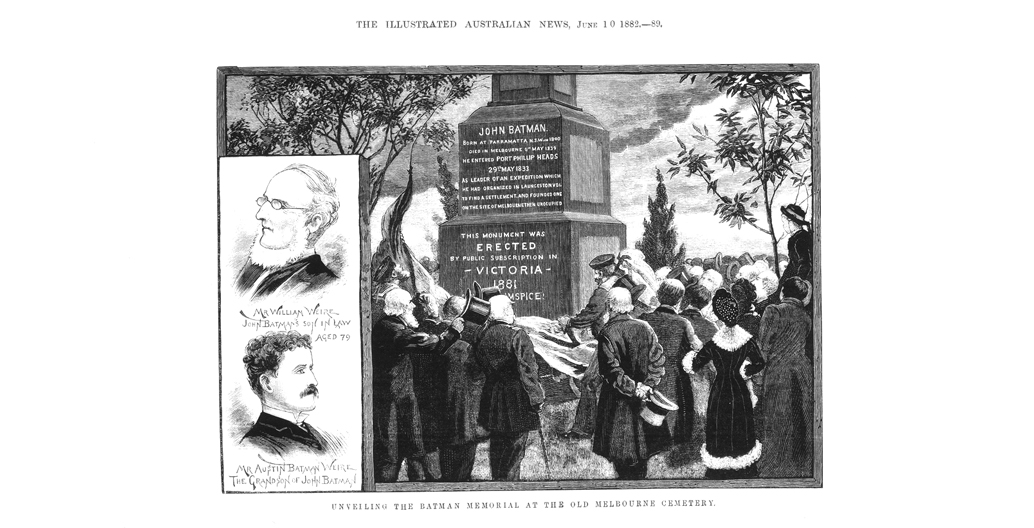

And then we venerate the men who did that work, as if the fact of the theft they supported in achieving was no more relevant than what the weather was like when Colonel Light was sitting at his drawing board creating his survey. And for these reasons it is so profoundly disappointing and concerning to hear that the State of Australian Cities has further participated in that whitewashing of Australian urban history by yesterday marking this statue of Colonel Light with a commemorative plaque marking this very conference. Surely the redress of land justice in this country will have to begin with refusing in future to participate in such wilful denial, or to at least offer a more considered and accurate account.

Melbourne circa 1854. Image: Nathaniel Whittock.

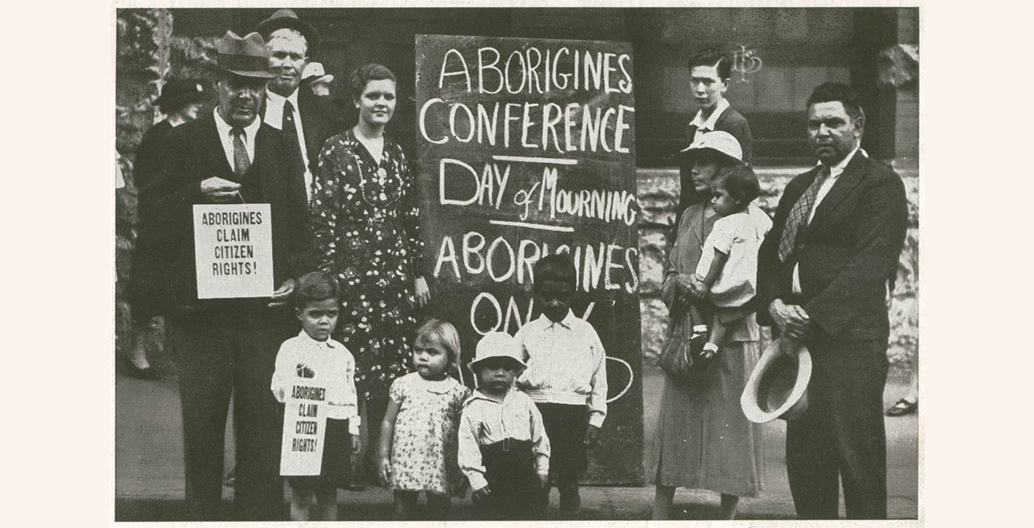

‘Aborigines Day of Mourning, Sydney. 26 January 1938’. Image: State Library of NSW.

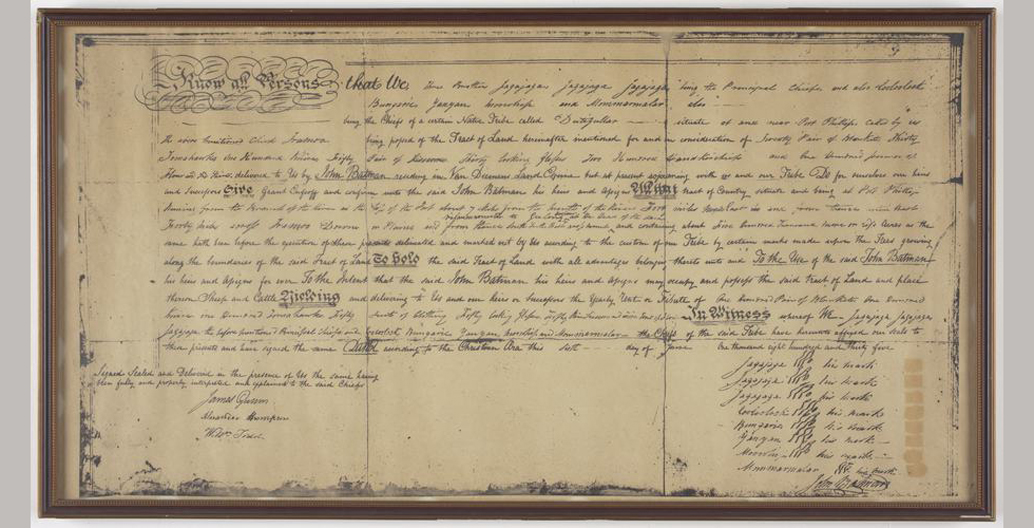

A framed print copy of the Batman deed, a disputed document establishing Melbourne's settlement. Image: SLV.

Melbourne settlers unveiling the John Batman memorial at the old Melbourne Cemetery, now the Queen Victoria Market in 1882. Image: SLV.

We have to work harder in the face of this denial and it is for that reason that in this lecture I’m inviting us to consider together a way of thinking about the public city, the just city, the future city as urban Country. Of course the city is a place undeniably difficult to make connections to Country, as Timmah Ball so well observed in Meanjin recently: “Finding the dreamtime hidden among skyscrapers, heavy traffic and boutique retail” is not straightforward. But thinking the urban as already Country means we can find new ways to consider the responsibility that settlers bear for coming into a rightful sovereign relationship with Country, to become more properly people that can share Country. If we are to think more coherently and honestly about the Australian urban context, then we must be willing to allow our categories and theories, our practices and systems, to be complicated and troubled by the underlying structure of settler-colonial relations.

What, then, is the task ahead for urban scholarship and practice in Australia? Perhaps the most obvious of our responsibilities is to reflect on the history and legacy of city-building in Australia, and accept that spatial systems, practices and technologies have been central to the dispossession and marginalisation of Indigenous peoples for more than two centuries.

‘Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyhee‘ (2016) commemorates Melbourne's overlooked Indigenous history. Image: Canley

Melbourne Festival brings together elders from the five clans of the Eastern Kulin nations to open the festival.

A mural of Reko Rennie's on Greville St in Prahran, Melbourne. Image: Fernando de Sousa.

But this is not a matter of abstract scholarship or theory, nor is it a matter of uniformity of practice or standardisation of procedure. It is about us, who we are. For that invitation asks us to consider unlearning ourselves, unpicking what we know and why we know it, what we don’t know and why we don’t know it. These are questions for all of us living and working in and on urban Country. For how can we as urban scholars speak of ourselves as a field of practice and scholarship that is all about space and place, all about people-place relationships and futures when we haven’t done the basic work of coming to terms with where and who we are? We can lay no claim to intellectual maturity or intelligence, no claim to fully understanding our cities and the way we occupy our spaces and live our lives, until we begin to acknowledge and recognise the work needed to come into a meaningful, right relationship with the invitation of Indigenous sovereignties.

Urban Australia is always already Country and this matters for all of our sustainable urban futures.

––

Professor Libby Porter is the RMIT Vice Chancellor’s Principal Research Fellow. Her research is about how urban development causes dispossession and displacement and what we should do about it. Her work has looked at these questions in a number of different ways including: Indigenous rights in urban planning and natural resource management; cities and diversity; gentrification and displacement; the impact of mega-events on cities; sustainability and urban governance.