Legacies of Empire: Control by design

When the British began planning Australia’s cities, located far from the centre of Empire, staving off rebellion was front of mind. Their anxiety can still be read, and felt, in the way Australians shape and inhabit public space today.

British attempts to assert dominance on a far-away colony were achieved through the execution of planning policies in the initial townships. These old imperial concepts of planning still have direct impacts on how Australians interact with public space in the inner city.

The use of public space in cities around the world is an effective way for both governments and citizens to express themselves. These uses include: exercising authority, as well as challenging it; celebrating and mourning; and casual recreational activity. These ways of engaging with public space have never quite translated into the Australian context.

This is because the architecture of public spaces provided the environment for colonial dominance to be achieved. While towns and new suburbs in the young colony were deeply influenced by European urban design, a key feature was excluded – the piazza. Governor Richard Bourke made very clear to surveyors that new towns in New South Wales (which at the time encompassed present-day Victoria) must not include public squares as these could promote rebellion.

Bourke’s deliberate exclusion of a city square may not have stopped democracy from finding its way into the eastern colonies. However, his wish to prevent mass public gatherings in the city was certainly realised.

In Melbourne’s case, this occurred long after the establishment of Victoria as a separate colony with a democratically elected parliament. Colonial controls over how people used public spaces can still be felt today as the city seeks to consolidate suburban and urban living.

Elevated views of the State Library of Victoria's construction work. Image: SLV.

View from the terrace of the State Library of Victoria after the removal of trees on the south lawn. Image: SLV.

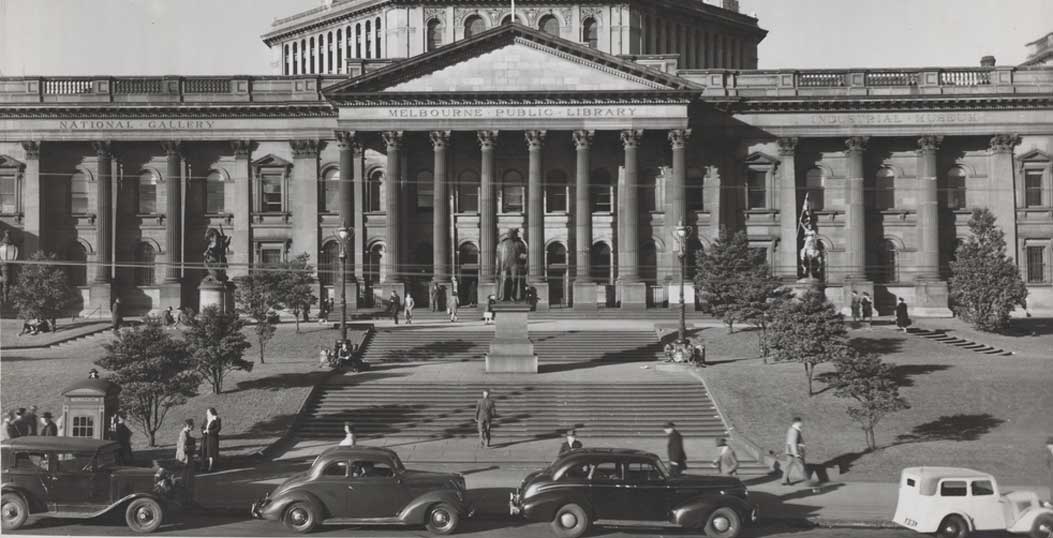

The then Melbourne Public Library pictured between 1930 and 1939 (image courtesy of the SLV).

State Library of Victoria's front lawn today. Photo: Nicholas Corner

Control by design

The placing of ornate, iron, wooden, or stone fences at first glance seemed to serve a purely decorative purpose. It can still be seen in the bluestone footings around the Carlton Gardens and State Library of Victoria where the iron fences once stood.

This form was a disguise of the function so people could not climb over, slide through, dig under, and sometimes see over these barriers. Gates were opened at a particular time of the morning and locked at sunset to deny access to the public under the cover of darkness.

As a result, the implied loitering that comes with public spaces is foreign to inhabitants of Melbourne. We do not know what to do with them.

Even today, the city’s main square (Federation Square) was not designed as a place to be in. It was designed as a place to go and do things in. Hence we find shops and galleries and organised events there. For a city square to be completely successful, it must feel natural to use, to just be there.

A city deprived of life in public space

Bourke’s demand to the early surveyors became part of the way Melburnians lived and experienced the city as Melbourne grew as a “destination city”. People travelled to and from places with no incentive to interact with the urban landscape along the way.

The central business district developed into a “9-to-5” place. People came to shop and work, then retreated back to their suburbs at the end of the day. As a result, an importance was placed on suburban life.

Discussing living on Little Lonsdale Street in the Melbourne CBD in the late 1970s, Marisa Sillitto described it as “being as deserted as war-torn Berlin”. It was not until planning policy shifted in the 1980s, and renewed investment and interest in the inner city accelerated, that the idea of civic spaces and communal environments began to embed themselves in our urban consciousness.

Aerial view of Federation Square.

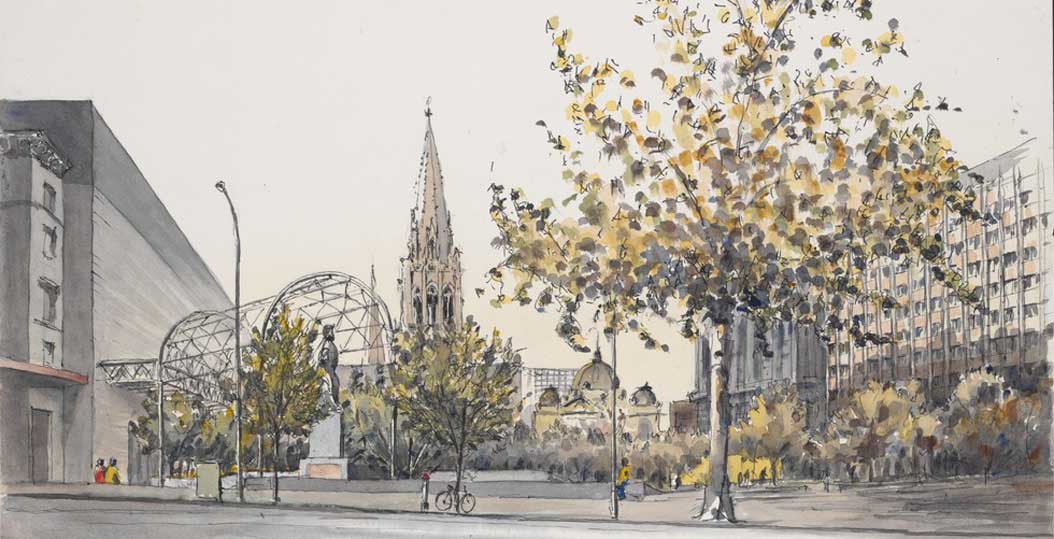

Brian Lewis' 'Flinders Street, 8 am. rush', looking south to City Square. Image courtesy of SLV.

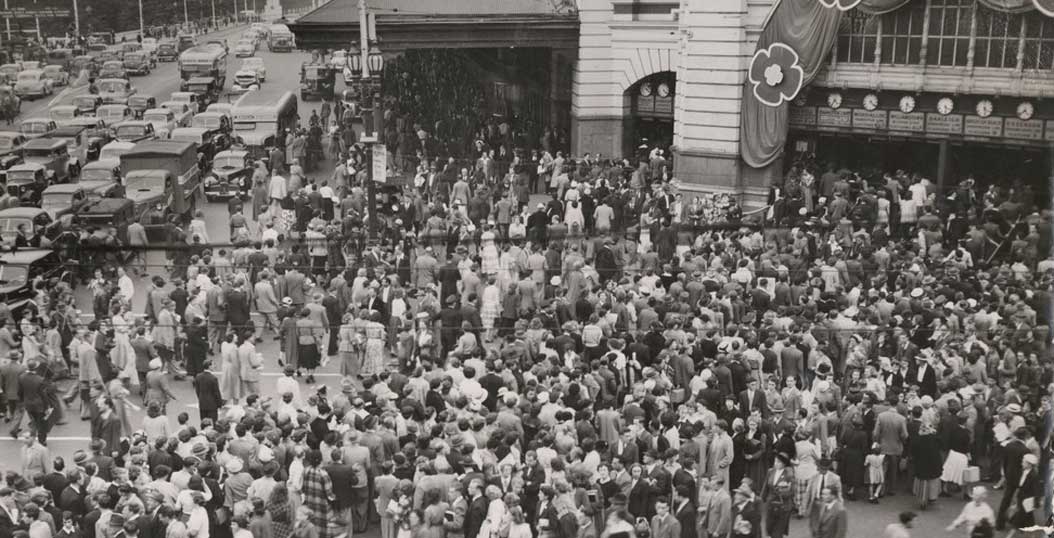

Large crowd of people at Flinders Street Railway Station, Melbourne, during tram strike (1954).

Aerial views of Carlton and the Royal Exhibition Buildings. Image: SLV & Francis Hodgson.

Finding alternatives to controlled spaces

Without a city square and with clear boundaries set around parks and gardens, Melburnians responded by finding other places to gather. Some groups responded by acquiring impressive private buildings, such as the Trades Hall. The general public gathered “under the clocks” of Flinders Street Station, or on the steps of Parliament House.

These are still gathering places today, even after City Square (1980) and Federation Square (2000) opened. Public spaces were not built into the fabric of the city and as a result they feel artificially imposed on the urban landscape and awkward to use. The city was designed as a place where interacting with public space was discouraged.

Melburnians seem to meet in places such as cafes, bars and pubs, with little reason to stop along the way. People organically found ways to interact with what little space they had, and we have seen the rise of laneway culture and street art as a response.

But, as we have seen through colonial design principles and the construction of spaces like Federation Square, looking to the past for context is vital to planning successful public spaces as functional, open and communal places for people to express themselves.

![]()