Disruptive design: placemaking in times of crisis

When recession strikes, what does it mean for design and the arts to have a meaningful role in community development? Jason Schupbach, outgoing director of Design and Creative Placemaking at the National Endowment for the Arts in the US, reflects on a near-decade spent answering just that question.

In the wake of the 2008 US recession, President Obama tasked 18 federal agencies with rebuilding local economies – the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) was one of them. That presented Jason Schupbach, the director of Design and Creative Placemaking at the NEA, with a question: what does it mean for design and the arts to have a meaningful role in community development? The answer came in the form of Our Town, a program designed to “support projects that help to transform communities into lively, beautiful, and resilient places”.

Described as a “champion” of urban design, Jason was in Australia for the City of Melbourne’s Knowledge Week. He spoke to Foreground about the lessons learned from the program, and more broadly about how discussions over “placemaking” don’t have to end in arguments over gentrification.

FG: Your job title includes the term “creative placemaking”. How would you define that term?

JS: When I started at the NEA it was the 2008 recession and the US was in a lot of trouble, the housing market and people’s mortgages were all upside down. People went underwater on their mortgage, where their house was worth less than what they owed on it. Traditionally in the US, if there was a recession people moved to where the jobs were. That couldn’t happen this time, because they couldn’t sell their house.

So the federal government responded with “place-based initiatives” across 18 different agencies, and we were one of them. That raised a question: what does it mean for the arts and design to have a meaningful role in community development? From that came the term “creative placemaking”. It was a made up federal term, but it simply defines role of artists, arts organisations and designers in making a “good” place. So, if you have a transit strategy, a housing strategy, a safety strategy, then what’s your arts strategy for making a place better? That’s what creative placemaking means to me.

Affordable living units for artists in Hamilton, Ohio.

Jason Schupbach pictured at the NEA. Image: Arizona State University

Rolling Rez Arts is a mobile arts space, business training centre, and mobile bank.

Juxtaposition – a Minneapolis youth arts centre – pictured with its renovated Community Design Studio.

Community mural project, Sioux Falls Arts Council. Image: NEA: Exploring Our Town

FG: What would an arts discipline bring to the development equation that’s unique?

JS: I think a lot of community development is very linear. Say if you’re asked to create affordable housing, you don’t often find people really thinking about an appropriate location or how it might mesh with the culture of the people using it. If it’s being designed for immigrant communities: how are their family lives structured, how is their culture expressed? That’s something an artist might be able to see and help the designers of a project design with these questions in mind.

FG: Would a designer also see that?

JS: Yeah absolutely, I put artists and designers in the same bucket as creative thinkers. But not all designers – with respect to affordable housing – think with that creative lens, at least in the US. So we have institutes where we’re trying to help improve the design of affordable housing, that we fund through an organisation called Enterprise Community Partners. They bring in affordable housing developers and help them think through how to design better affordable housing.

FG: I hesitate to use this word, but you might look to an artist for a disruptive outcome?

JS: I think that’s a fine word to use. There’s a project down in Charlottesville Virginia, which is an expensive college town because of the University of Virginia. Right now a designer has been using an arts-based community practice to engage the local community on the planning part for the redevelopment of an affordable housing project. So they’ve been doing arts-based events as part of the planning process to bring people out, to open them up, and to really hear what the concerns of the people living in housing are. So it wasn’t just like we had a community meeting and asked them why they didn’t show up – instead we showed up and listened.

FG: From that perspective, we’re not talking about conventional “plonk art” here, are we?

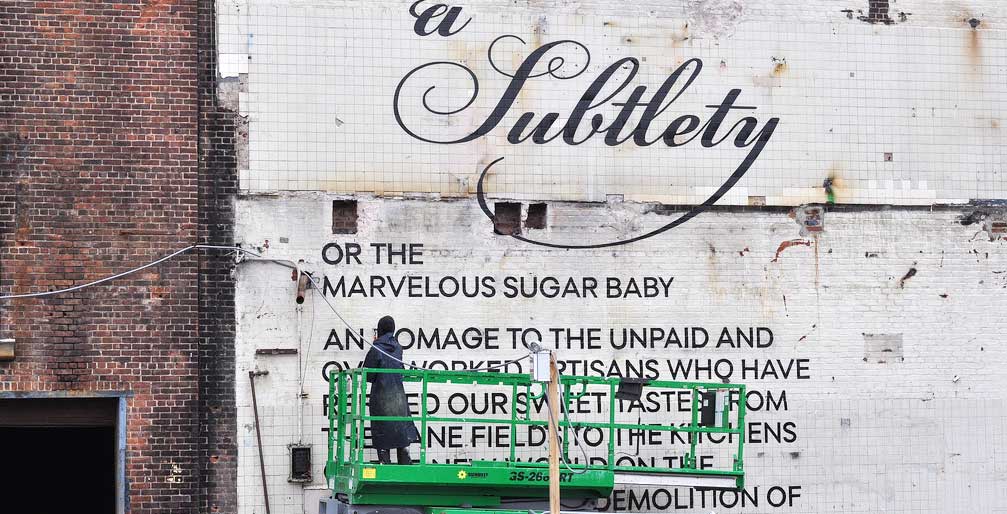

JS: We call it “plop art”. “Plonk” – I like that better. But I believe that that kind of public art really does have important things to say. I think temporary public art has a big role, too – like Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, or the Marvellous Sugar Baby in Brooklyn’s old Domino Sugar Factory. This changed the game on temporary public art in the US. It created a conversation about the history of sugar, created a conversation about redevelopment in New York City. I also really believe strongly that in some cases the process of creating a piece of public art can be more important than the final product itself.

FG: Have there been any failures from your perspective?

JS: We need to equip more artists and designers with community development skill sets. I’m not sure we’ve focused enough on preparing artists and designers to step into these conversations. They’re not learning community organizing in school, especially not in art school! There’s so much focus on just the object.

FG: And your favourite projects?

JS: I love when someone blows me away with something next level. We funded a project called Datagrove in association with Silicon Valley’s ZERO1 Technology and Art Festival. It was a big steel structure with little bot faces on it that when you walked up, would pull the number of hashtags people were hashtagging in San Jose. In that moment, it would tell you what people were talking about in that place. If people were talking about Oprah, it would ask: what do you think about Oprah?

Keep in mind these were the early days of Twitter, circa 2012, so I was amazed – now everybody’s phone could probably do it. What was cool about that project was it wasn’t just about creating the piece, but it was also about creating places in downtown where people normally wouldn’t go. This piece was put in a plaza that had previously been locked for safety reasons. They were re-opening the plaza permanently, and this was the piece to invite people into this new space. It was public art, it was tech, it was temporary, but it was also about re-engaging citizens in this new place downtown. I love these multifaceted projects.

A reflection of 'A Subtlety, or the Marvellous Sugar Baby'.

Future Cities Lab's 'Murmur Wall'. Peter Prato Photography

Exterior of Brooklyn's Domino Sugar Factory during 'A Subtlety''s run.

An inhuman scale: Punters take a close up look at 'A Subtlety'.

There’s an interesting project in Natchez, Mississippi which is just starting, which is going to draw together Kentucky or Natchez-born artists and the area’s health insurance companies. The African-American community has not felt engaged by the health insurance companies in a way where they feel comfortable getting insurance from them – there are a lot of issues there around our racist history to pick apart. So, an artist organisation is going to start working with the health insurance companies to do artist residencies in these communities, to help educate the population about their ability to get access to health insurance, which is important for their long-term health.

So it’s a really beautiful, careful project that is going to culturally engage people and meet them where they’re at. Rather than pushing insurance product on people, this project is taking the time to really understand what the issues are. That kind of beautiful stuff is happening all across America, but it never gets reported. I’ve always said to folks if you want to feel good about what’s happening in the US, you should come and be a grant reviewer. Because when you read what communities are trying to do and the people that are out there trying to make a difference in our country, it’s really heartening.

FG: I want to talk the idea that once artists move in, the neighbourhood will be gentrified.

JS: I don’t like that word because I don’t think it’s specific enough and I think we have a very immature conversation about gentrification. People make a lot of assumptions about what gentrification is and what they mean by it. One of the primary concerns in gentrification is displacement, right? Displacement of humans and people who used to be in a neighbourhood, the displacement of the culture of a place, and displacement of businesses. So all three of those things need different kinds of attention.

Just because artists move into a neighbourhood doesn’t mean that it’s going to be gentrified. It’s also not true that artists are rich people that are bringing money with them. Most artists are low income in our country, and in need of affordable housing as much as anyone else. I feel like if you’re focusing on displacement in a neighbourhood, blaming the artist for that is not the right strategy. Sit on your neighbourhood association boards, step up and start helping preserve the community that’s there. I think that’s the responsibility of all of us.

FG: And the argument that city beautification through the arts is likely to increase property values?

JS: That’s so classist, to say that lower income people don’t deserve a beautiful place, right? That is BS to me, everybody deserves a beautiful place, and there’s no reason why a beautiful place can’t be affordable.

–

Jason Schupbach is the outgoing director of Design and Creative Placemaking at the US’ National Endowment for the Arts. You can revisit his Melbourne Knowledge Week keynote below.