Deep in the water

The knowledge of traditional owners is vital when it comes to making development decisions around water, says Sandra Harben, researcher and Whadjuk/Balardong Nyungar woman, in conversation with Rosie Halsmith.

Sandra Harben is a Traditional Owner whose family affiliations are within the Whadjuk Nyungar Boodjar, or Country, which incorporates Perth and its surrounds, and the Balardong Nyungar Boodjar, or Country, which is on the other side of the Darling Escarpment.

Harben has been interested in Nyungar research for over 30 years. Here, she shares knowledge about Nyungar culture, history and language, particularly as it relates to water and water bodies in Perth, with Rosie Halsmith.

Rosie Halsmith: The landscape of Perth is defined by its water bodies – the Swan and Canning rivers and chains of coastal wetlands. What is the significance of these systems, and the forces that have shaped the landscape in which we live?

Sandra Harben: In the Nyungar belief system, the creator of our Boodjar, our Moort and our Katitjin – our people, our family and our knowledge – is the Waagle, the Nyungar rainbow serpent. Water is a huge life force for us, and our belief system tells us that the spirit of the Waagle lives in all the freshwater sources.

All of these freshwater systems are very important, not only because of the belief in the Waagle, but also because they are places rich with sources of food, medicine and plants, and habitat for native species and birdlife.

RH: In the years since colonisation, Perth’s water systems have been significantly altered. Perth’s great lakes have been filled in and a port created at Fremantle, and there has been a gradual and continual reclamation of land around the edges of the Swan River. The ecological impact of these decisions is now being acknowledged. Could you speak to the cultural significance of these alterations?

SH: Our Waagle is the giver of life – without water, you can’t live. The Waagle is a freshwater being – he can’t live in salt water. In the case that salt water replaces fresh water, the spirit of the Waagle will no longer be found, and we’re no longer going to be linked culturally to that place.

For example, before colonisation at Fremantle Port, which the Nyungar call Walyalup, you had the wardan, or the ocean, and then you had the bilya, the fresh water. While those two might at times have come together and met as the tides rose, there was a clear separation of the ocean from the fresh water of the Swan River.

In the area where the ocean and the fresh water met, there was a limestone crossing. When the tides were low, the Nyungar used this area to cross from the south side across to the [north].

Our Dreaming story tells about how the Waagle fought the saltwater crocodile so that the salt didn’t come down into the fresh water. The Waagle talked with the other mythological beings – Urumbuk, the lizard; the Wardan Dwerda, the sea dogs; and the Dwerda, the land dogs. They told the Waagle that the saltwater crocodile was going to come into the Swan River, and they said, “You must stop the salty from coming in.”

So, the Waagle went and fought with the crocodile. The Waagle bit the tail off the crocodile and he floated out to create Carnac Island, and then part of the body of the crocodile formed Garden Island, and the rest of its body formed Rottnest Island.

Now, the Wardan Dwerda and the Dwerda keep guard. They watch that the crocodile, who’s in three parts, doesn’t move, so that he never comes down into the fresh water. That’s our story about that separation of the salt and fresh water.

Since colonisation, there’s an urge for rapid urban development, which includes creating the Fremantle Port for the transport of goods. [Irish engineer] C. Y. O’Connor was engaged to create this new port. Of course, they blew the limestone bar up, which means they blew the crossing up and brought salt water into the Swan River.

This impacted our beliefs, our Dreaming. Although our stories will never change, the landscape will change, but we will continue to tell our stories as they have been told for thousands of years.

RH: What is it important for people to know as they move along freshwater systems on Whadjuk Nyungar Country?

SH: Nyungar people never camped on the edge of the fresh water. They camped further away. There are many laws around the waterways, which kept Nyungar away.

So what does that do? It ensures that you’re protecting the habitat and respecting the belief in the Waagle. Just as importantly, you’re not creating any debris, and you’re not contaminating the water.

The way urban development is today is at odds with the way that Nyungar protected and looked after the waterways.

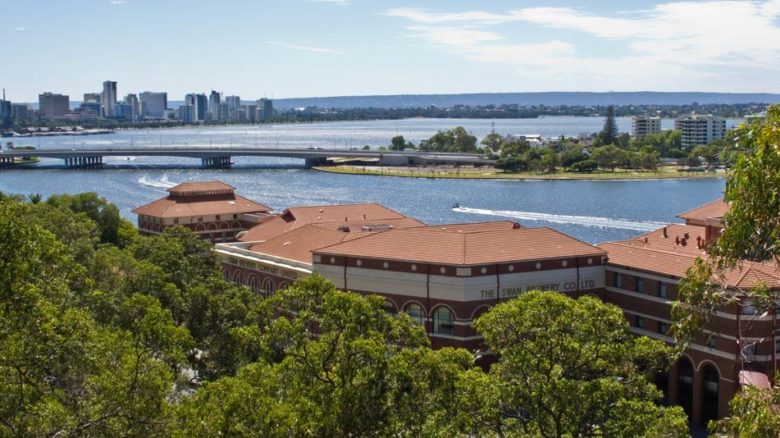

Built on contested grounds: the Old Swan Brewery site. Image: Graeme Churchard CC by 2.0

The Fremantle coastline separates the river and the ocean. Image: Tourism WA

Bibra Lake in Beeliar regional park, Perth. Image: Brettanomyces, Flickr CC2.0

Community protests against the Roe 8 highway link saved Beeliar wetlands. Image: GreensMP, Flickr CC2.0

RH: Whadjuk Nyungar people have been caring for Country for millennia – and with this, are the custodians of tens of thousands of years of knowledge about this place. What processes need to be in place so that planners, designers and policy makers can understand, respond to and, if appropriate, integrate traditional ecological knowledge into projects and strategies?

SH: Engagement is fundamental to any project. Engaging with Nyungar people about anything to do with the Boodjar absolutely needs to happen. Whether it’s planners, architects, landscape architects, designers – they all need to have a cultural knowledge. Aboriginal cultures are the oldest living cultures in the world, and with that comes the stories.

Any design consultant who is engaged to do a project must have written into that tender process to engage with the local Aboriginal people on whose Country they are going to be working. That should be the number one, primary criterion for any architect, any landscape architect, any planner, any designer.

It’s a tangible demonstration of the respect that people have for Nyungar and other Aboriginal people. It’s a way of showing and demonstrating that we have a voice – we have a story that’s associated with our Boodjar.

RH: In recent years, community awareness around the value of Perth’s water systems has come to the forefront. Opposition to the proposed Roe 8 road connection, and the subsequent protection of the Beeliar Wetlands, became a key state election issue in 2017. Most recently, the proposal to develop a marina at Point Peron was scrapped in response to community protests. Do you think there’s a shift in general social awareness regarding the importance of our water systems?

SH: Absolutely. In the 1980s, during the protest against the development of the Swan Brewery on the banks of the Swan River, how many non-Nyungar people joined in the protest for over 100 days to say, “Yes, we must protect this?” I could probably count them on one hand.

In the case of the protest for Beeliar Wetlands, places like the City of Cockburn and the City of Fremantle are very forward-thinking in Aboriginal affairs, and particularly in Nyungar affairs. When you’ve got people in positions of power who are aware, respectful and do a lot of work in the Aboriginal space, it makes a huge difference.

RH: When you move across Perth, how can you tell that you’re in a successfully designed space?

SH: It tells you a little bit about the place or where you are. When you talk to the Traditional Owners about a space and how it can be interpreted, and how it can be designed to give you that sense of connection to what’s there, it puts you in good stead for when the project is finished, so that it is something that is respectful, and tells a story.

This article was originally published in Future West (Australian Urbanism).

Rosie Halsmith is co-director of To & Fro Studio. She previously worked as a landscape architect at UDLA Fremantle. Sandra Harben is a Whadjuk/Balardong Nyungar woman and a research associate at Curtin University, Western Australia.