Decolonising agriculture: Bruce Pascoe’s ‘Dark Emu’

Australia’s colonial history has characterised indigenous people almost exclusively as nomadic hunters. This exclusive extract from Bruce Pascoe’s ‘Dark Emu’, reveals a long history of indigenous agriculture, a history that predates the pyramids, but which was omitted from the history books.

Foreground advises that images of deceased Indigenous people are contained within this article.

After my book on the Australian colonial frontier battles, Convincing Ground, was published in 2007, I was inundated with more than 200 letters and emails – many of them from fourth generation farmers and Aboriginal people. Farmers sent me their great grandparents’ letters and documents about the frontier war and Aboriginal people sent new information on many of those same battles.

I already had a pile of information collected from research conducted too late to make it into Convincing Ground and after following the leads from correspondents I discovered much more.

I began to see a consistent thread running through the material; not only that the frontier war had been misrepresented in what we had been taught in school but also that the economy and culture of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people had been grossly undervalued.

I knew that if I were to use all the new material in another book I would have to begin from the sources upon which Australia’s idea of history is based: the journals and diaries of explorers and colonists.

These journals revealed a much more complicated Aboriginal economy than the primitive hunter-gatherer lifestyle we had been told was the simple lot of Australia’s First People. Hunter-gatherer societies forage and hunt for food and do not employ agricultural methods or build permanent dwellings; they are nomadic. But as I read these early journals I came across repeated references to people building dams and wells, planting, irrigating and harvesting seed, preserving the surplus and storing it in houses, sheds or secure vessels, creating elaborate cemeteries and manipulating the landscape – none of which fitted the definition of hunter-gatherer. Could it be that the accepted view of Indigenous Australians simply wandering from plant to plant, kangaroo to kangaroo in hapless opportunism was incorrect?

It is exciting to revisit the words of the first Europeans to ‘witness’ the pre-colonial Aboriginal economy. In Dark Emu my aim is to give rise to the possibility of an alternative view of pre-colonial Aboriginal society. In reviewing the industry and ingenuity applied to food production over millennia, we have a chance to catch a glimpse of Australia as Aboriginals saw it.

Many readers of the explorers’ journals see the hardships they endured and are enthralled by the finds of grassy plains, bountiful rivers and sites where great towns could be built; but by adjusting our perspective by only a few degrees we see a vastly different world from the same window.

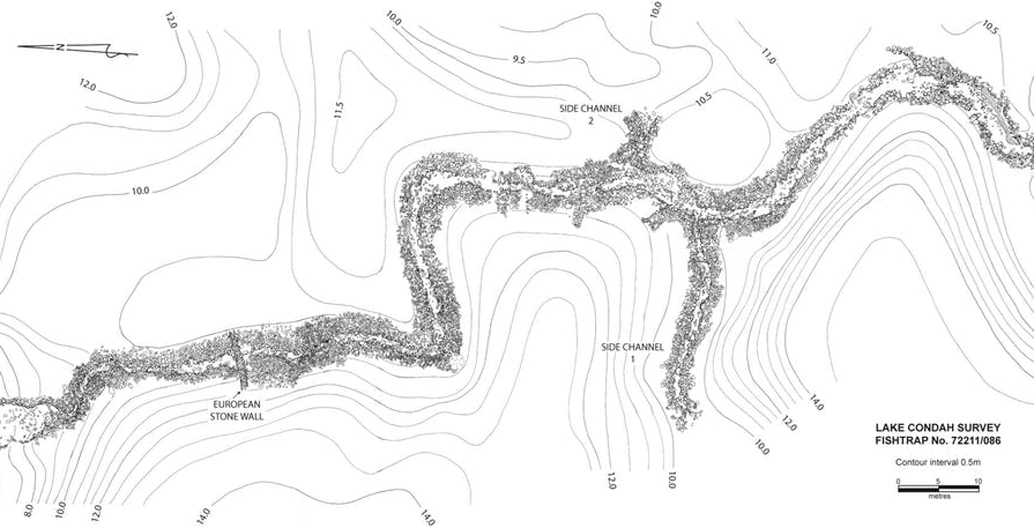

A video from the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation outlining their bid to get the Budj Bim Cultural Landscape listed on the World Heritage Register. Located in Lake Condah in south-western Victoria, this aquaculture network is over 6,000 years old, bucking the myth of Indigenous Australians being nomadic hunter-gatherers.

Remnants of stone houses, Lake Condah. Image: Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation.

A 200-metre-long fish trap channel at Lake Condah mapped by Dr Peter Coutts of the Victorian Archaeological Survey.

The first colonists had their minds wrought by ideas of race and destiny; by the rumours heard as a child of the great British Empire. They were immersed in these stories as infants and later while marching in to school to ‘Men of Harlech’, standing to attention for ‘God Save the King’, and poring breathlessly over the stories of Horatio Nelson, the Christian Crusaders, King Arthur, Oliver Cromwell, and of course, Captain James Cook.

Europe was convinced that its superiority in science, economy and religion directed its destiny. In particular the British considered their successes in industry accorded their colonial ambition a natural authority, that it was their duty to spread their version of civilisation and the word of God to heathens. In return they would capture the wealth of the colonised lands.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was still to come but the basis of it, the gradual ascent from beast to civilised man, dominated the psychology of Europe at the time. The first British visitors sailed to Australia contemplating what they were about to find, and innate superiority was the prism through which their new world was seen.

When Darwin’s theory was put forward, it gave comfort to those who believed it was their right and duty to occupy the ‘empty’ land. As anthropologist Tony Barta commented:

The basis of that view was historical: it held that the advance of civilisation was a triumphal progress, morally justifiable and probably inevitable. When Darwin lent his great gifts and influence to making the disappearance of peoples ‘natural’ as well as historical, his theory … could serve as an ideological cover for policies abhorrent to his humanitarian and humanist principles. Darwin’s fateful confusion of natural history and human history would be exploited fatally by others.

Under the influence of these cultural certainties how would it have been possible for the colonists not to believe that Englishmen were on the steepest ascent of human endeavour? How would it have been possible for them not to believe that the world was their entitlement and their possession of it ordained by their God?

To understand how the Europeans’ assumptions selectively filtered the information brought to them by the early explorers is to see how we came to have the history of the country we accept today. It is clear from their journals that few were here to marvel at a new civilisation; they were here to replace it. Most were simply describing a landscape from which settlers could profit. Few bothered with the evidence of the existing economy because they knew it was about to be subsumed.

Skewed views and misconceptions

The following story serves as a good example of the power of these assumptions and the need for colonists to legitimise their presence in the colonial field.

The Beveridge family had prospered on the colonial plains around Melbourne to the degree that a district was named after them. Once their wealth was consolidated they decided to send a son, Peter, and his friend, James Kirby, to an area of the Murray River which had never seen European occupation.

The young men drove 1,000 head of cattle from the outskirts of Melbourne to the Murray River in 1843. They came across some natives and Beveridge wrote in his diary that:

many of them had green boughs in their hands, and after ‘yabber yabber’ they began swinging the boughs over and round their heads, and shouting ‘Cum-a-thunga, cum-a-thunga.’ We of course did not know what their meaning was by these antics, but we guessed that by it they meant we were welcome to their land, and we made them understand that we were highly pleased at their antics and quite delighted at the words ‘cum-a-thunga.’ When they saw we were so much pleased at their conduct, three or four of them jumped into the water, and swam across and gave us a lot more ‘cum-a-thunga,’ so much so that they almost made themselves hoarse with shouting ‘cum-a-thunga’.

You have to work hard to convince yourself, or the governor, that Aboriginal people were delighted to give away their land.

In subsequent days the two young colonials observed substantial weirs built all through the river system and speculated on who might have built them. As they were the first Europeans in the area they conceded that they were probably built by the ‘blacks’.

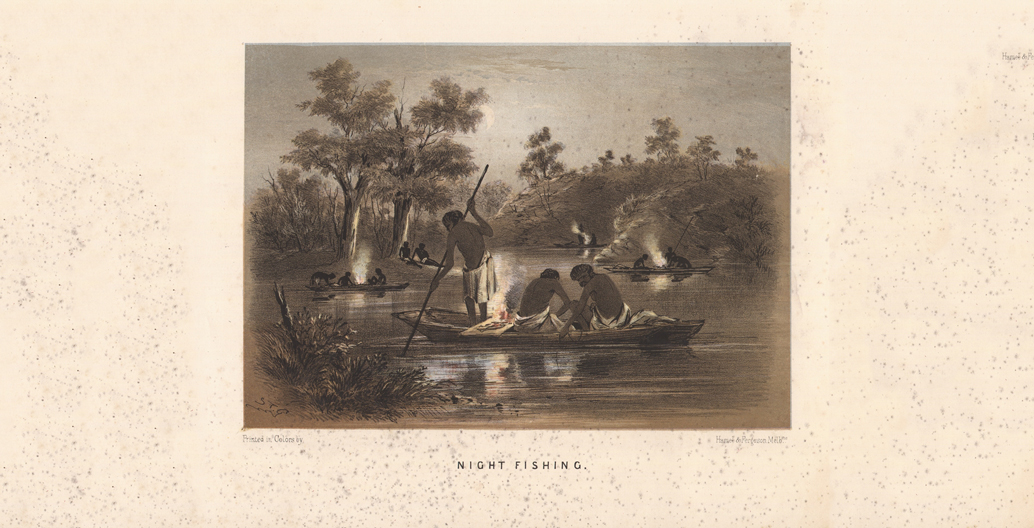

Later they witnessed the people fishing with canoes, lines and nets. The purpose of the weirs gradually became clear. They were made by damming the stream behind large earthen platforms into which channels were let in order to direct fish as required. On one particular day Kirby noticed a man by one of these weirs. He wrote that:

a black would sit near the opening and just behind him a tough stick about ten feet long was stuck in the ground with the thick end down. To the thin end of this rod was attached a line with a noose at the other end; a wooden peg was fixed under the water at the opening in the fence to which this noose was caught, and when the fish made a dart to go through the opening he was caught by the gills, his force undid the loop from the peg, and the spring of the stick threw the fish over the head of the black, who would then in a most lazy manner reach back his hand, undo the fish, and set the loop again around the peg.

How did Kirby interpret this activity? After describing the operation in such detail and appearing to approve of the its efficiency, he wrote, “I have often heard of the indolence of the blacks and soon came to the conclusion after watching a blackfellow catch fish in such a lazy way, that what I had heard was perfectly true.”

Kirby’s preconceptions of what he was going to find on this frontier are so powerful that he skews his detailed observations to that prejudice.

View on the upper Mitta Mitta, Eugéne von Guérard (1863-1864). Image: State Library of Victoria.

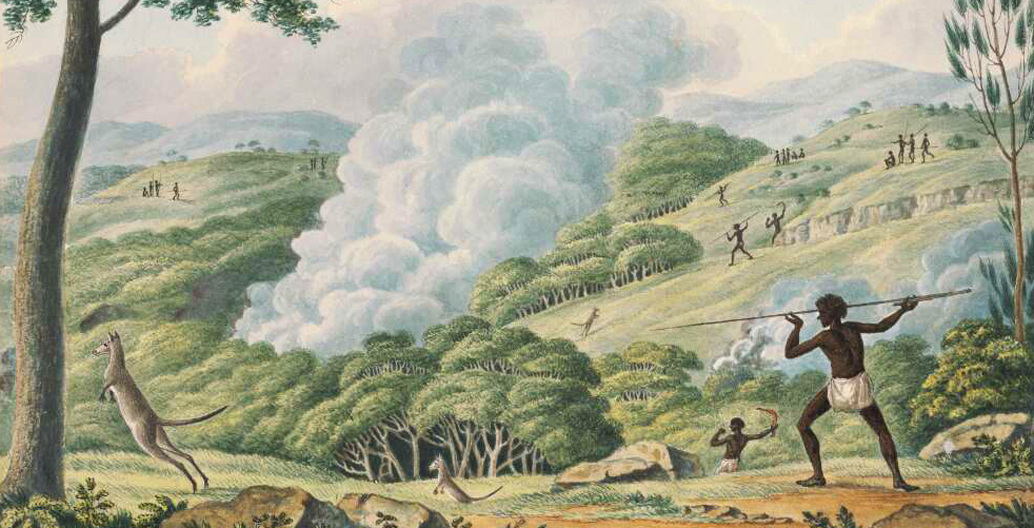

Aborigines using fire to hunt kangaroos. Image: National Library of Australia (NLA).

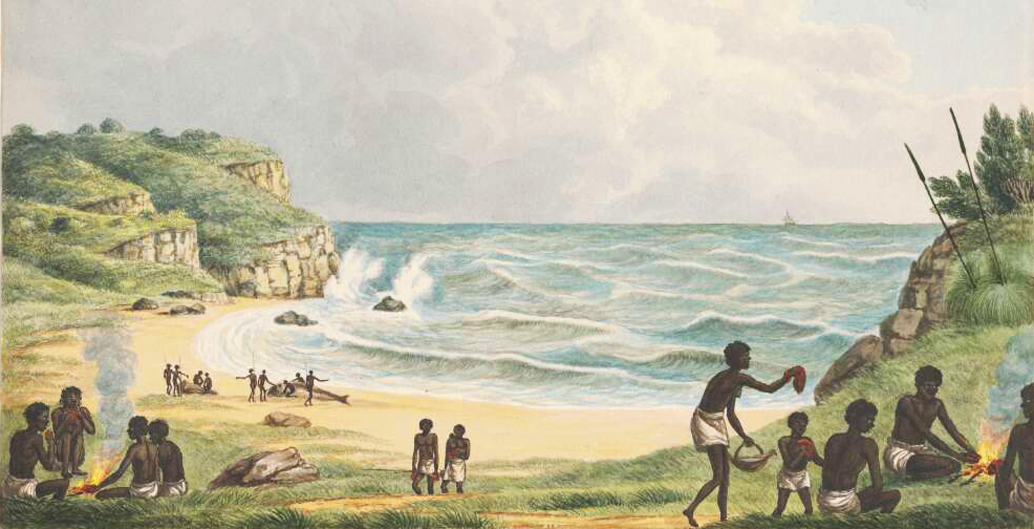

Aborigines cooking and eating beached whales, Newcastle, NSW (1817). Image: NLA.

Night fishing / S. T. Gill (1864). Image: State Library of Victoria.

Peter Beveridge wrote a book about his experiences with Aboriginal people and displayed all his and Kirby’s prejudices. Despite the fact that his work is crucial to what we know of the Wati Wati clan, and his list of words is one of the most significant, he can’t disguise his contempt. He refers to the old women as hags, continually refers to the Wati Wati as savages, and appears to have completely ignored the moiety and totemic system of their society.

Modern histories of the area claim Peter’s brother Andrew was killed by the Wati Wati after a dispute about blacks killing Beveridge’s sheep, but Kirby’s description of the event offers a startling insight into the real motivation.

Heavily armed warriors advanced on the station and ignored all other Europeans until they found Andrew Beveridge, the man who they claimed had been violating women. He was isolated and speared and his body symbolically daubed with ochre.

The problems at the Beveridge property, Tyntynder, followed a very familiar colonial pattern: initial acceptance followed by increasing suspicion and anger as the Europeans refused to allow the people to make use of their ancestral lands.

Kirby relates incidents of the war with relish but always cloaks the killings in euphemism:

The blacks ran into the lake, but the shore shelved in so far that it was not deep enough for them to swim or dive, they thus became very good targets for us. A lot of these fellows never came near the hut again, nor did they attempt to kill a man or beast, no! they were very peaceable after this … Sir Robert [a Wati Wati man], for instance, never killed anyone after this, he also may have died.

Kirby’s emphatic words hint at ghoulish glee.

His narrative continues: “It was open war now. If they caught us unguarded they would kill us, and we in return would (if we caught them) help ourselves.” The language Kirby uses may be euphemistic but the meaning is unequivocal. Tyntynder was at war with the Wati Wati despite the fact that at this stage of the settlement only one European had been killed by Aboriginals and that was for molesting women.

When Kirby and Beveridge chose to interpret the Wati Wati shouts of ‘cum-a-thunga’ as an invitation to take their land it set in train all the violence, bitterness and hardship typical of the colonial frontier. It was a land contest and neither side would withdraw from the battle.

In the dictionary he wrote in his retirement at French Island, Peter Beveridge does not give a definition of the first Aboriginal words he heard, but examination of other studies and discussions with linguists of the Wati Wati and the neighbouring Wemba Wemba language reveal a phrase ‘cum.mar.ca.ta.ca’, recorded by the Aboriginal Protector, George Augustus Robinson, one of the few who recorded language and cultural information. Its probable meaning is ‘get up and go away’. It’s an exclamation given great force, as Beveridge admits, and it is improbable that it represents an invitation to take the land.

There is also a strong possibility that within the phrase heard by Beveridge is the word, ‘karmer’, meaning a long reed spear, combined and added to the strongly intensive verb affix, ‘ungga’, and further combined with the plural first person pronoun we, ‘angurr’, thus ‘karmer ungga’ translates as ‘we will spear you’.

In any case Beveridge chose not to include in his dictionary the first phrase of Wati Wati addressed to him. Perhaps with greater knowledge he was not keen to remember it, having since learned the true meaning.

Kirby and Beveridge weren’t just pulling their own legs, they were pulling ours in an effort to disguise the means by which they took possession of a land. Their determination to seize the land had blinded them to the use the Wati Wati were making of it. In denying the existence of the economy they were denying the right of the people to their land and fabricating the excuse that is at the heart of Australia’s claim to legitimacy today.

Eric Rolls, in his epic A Million Wild Acres, described the desecration by sheep of the grasslands in the Hunter-Pillaga region. Rolls was a passionate man of the land who documented the misuse of soils and water by Australian farmers. He noticed that dispossession of Aboriginal people and destruction of their villages was followed by an equally rapid deterioration in the soil, the foundation of the pre-contact economy.

Farmers noticed the alarming drop in productivity over a mere handful of years as sheep ate out the croplands and compacted the light soils. “In Australia thousands of years of grass and soil changed in a few years. The spongy soil grew hard, the run-off accelerated and different grasses dominated.”

The fertility encouraged by careful husbandry of the soil was destroyed in just a few seasons. The lush yam pastures of Victoria disappeared as soon as sheep grazed upon them as the dentition of sheep allowed them to eat growth right to the ground, destroying the basal leaves.

The English pastoralists weren’t to know that the fertility they extolled on first entering the country was the result of careful management, and cultural myopia ensured that even as the nature of the country changed they would never blame their own form of agriculture for that devastation.

At the height of its productivity Australia supported large populations and, even after plagues of introduced smallpox and warfare had devastated the Aboriginal population, 500 people attended the last ceremonies at Brewarrina in 1885. Similar reports of large gatherings were described in most parts of Australia around this time despite the calamitous fall in population.

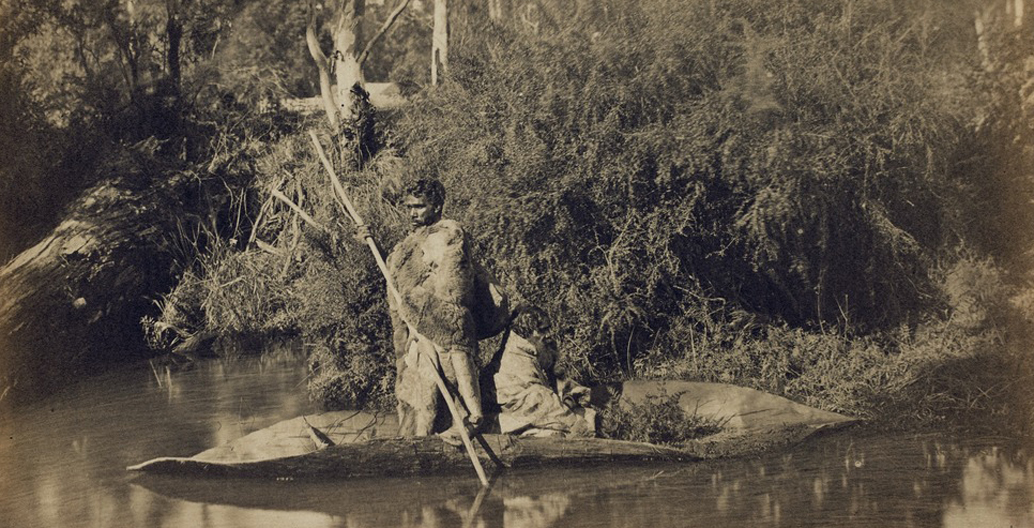

Two men in possum skin cloaks paddle a red gum bark canoe on the Yarra River, Fred Kruger (1870). Image via Culture Victoria.

Smith’s Crossing, Yea River, Toolangi, John Henry Harvey (c. 1875-1938). Image via Culture Victoria.

Aboriginal camp, Richard Daintree (1858). Image via Culture Victoria.

Aboriginals' farm near Mount Franklin, Richard Daintree (1858). Image via Culture Victoria.

Colonial Australia sought to forget the advanced nature of the Aboriginal society and economy, and this amnesia was entrenched when settlers who arrived after the depopulation of whole districts found no structure more substantial than a windbreak and no population that was not humiliated, debased and diseased. This is understandable because, as is evidenced by the earlier first-hand reports, villages were burnt, the foundations stolen for other buildings, the occupants killed by warfare, murder and disease, and the country usurped. It is no wonder that after 1860 most people saw no evidence of any prior complex civilisation.

Moreover, the perishable nature of materials used in Aboriginal storage devices ensured they would not be seen by archaeologists and the ferocity of the war meant such large stores of food could never be compiled again. The attacks by settlers on Aboriginals engaged in harvesting are much under-rated as one of the tools of war. Nutrition and morale plummeted as the croplands were mown down by sheep and cattle and people were prevented from protecting and utilising their crops. No better device, short of murder, could ensure the weakening of the enemy.

The archaeologist, Peter White, in his Agriculture: was Australia a Bystander? argues that de-population by disease and the arrival of sheep, which walked ahead of their shepherds, helped eliminate evidence of agriculture and its domesticates. This makes the evidence recorded by the earliest explorers and settlers so critical to our understanding of the pre-contact Aboriginal economy.

––

This is an edited extract from Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu (2014), published by Magabala Books.