Breaking rivers free: HYDRO/LOGIC

An exhibition by artist and ecologist Aviva Reed hopes to reconnect visitors with the forgotten systems that underpin our cities’ health.

Visual ecologist Aviva Reed wants Melburnians to think differently about the way their city works – most especially in its relationship to water and to soil. Her exhibition HYDRO/LOGIC, held at the City of Melbourne’s Library at the Dock, looks at the interdependent relationships between the capital’s waterways and the rest of the Victorian ecosystem.

“Water is a living organism and an entity in its own right,” says Reed. “”The Woi- wurrung peoples in the Wilip-gin Birrarung murron (Yarra River Protection) Act acknowledge water is a living organism and an entity in its own right – something I, from my ecological perspective also hold true – so I’m really interested in reframing the paradigms around water.” Reed says.

Historically, Melburnians have seen their waterways as a nuisance, with swamps, billabongs, creeks and rivers paved-over or re-routed. But while this might have seemingly positive short term benefits in protecting from flooding, as Reed points out it has some serious consequences for urban and ecological health in the long run.

“When you put in massive stormwater systems that take every single drop of water off a property and then pump it as fast as they can down to a creek running out into the ocean, it means no soil in the region gets any runoff,” says Reed. “But soil is going to be one of the main ways we’re going to keep our city cool and keep our trees healthy. One of the prompts I give in workshops is: does rain make rainforests or do rainforests make rain? It’s not just a coincidence that all the rain goes where the forests are.”

Aviva Reed.

Basic ecological literacy is something Reed is concerned about in her practice. Coming from a science background, the artist thinks this understanding is critically lacking when people conceptualise their city.

“I don’t think people spend much time thinking about the function of ecosystems, and the sheer extent of their connectedness” says Reed. “I’m really trying to break down a ‘vertical hierarchy’ that people seem to have with their city. We need to view the city horizontally, because actually in truth, the health of soil will be the dictators of its future.”

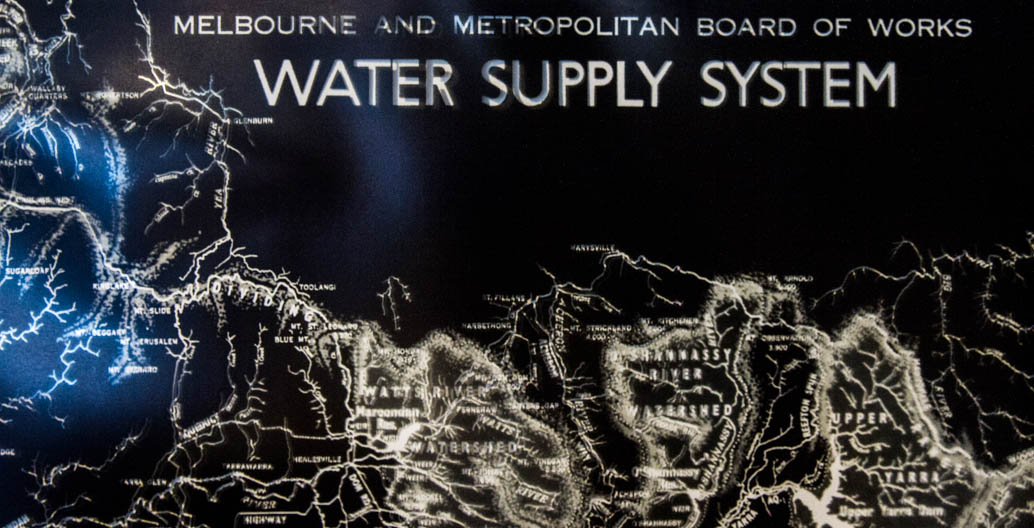

“One of the major conversations I focused on in this exhibition is how Victoria’s old growth forests are actually the city’s main water catchment,” she continues. “Our Eucalyptus Mountain Ash forests are facing ecological collapse… and when you look at a weather map, that’s where most of Melbourne’s rain occurs, meaning those forest systems support the city by providing the city with water.”

The exhibition draws together experts in ecology, mapping the microscopic life of our world.

The detritus of Melbourne's waterways.

Watercolour portraits articulate the relationship between Victoria's forests and Melbourne's rainfall.

Part of the exhibition presents the microscopic life within drops of water.

Reed also utilises writing as an element of her art practice.

Goblets of water from Melbourne's systems sit on plinths around the space.

Melbourne's water supply goes further beyond its reservoirs.

Recent environmental developments in Melbourne, such as the council’s Urban Forest Strategy, point to an emerging ecological awareness, but Reed says some initiatives designed to build a more resilient environment suffer from a lack of understanding of how ecological systems work.

“I teach ecological systems in planning design, but when I step outside of the academic space I find that basic ecology is a big leap for many planners. I think we’ve got to get more ecological literacy into curriculums, starting with the thermodynamics that underpin most systems,” says Reed. “I’m finding that a lot of urban parks are missed opportunities as they’re missing strata. If people understand how forest systems work, you then understand how to build parks with mutually reinforcing connections, because you need to have a canopy, a second-storey, and a ground floor. Right now some parks function as islands of air, with vast lawns and isolated trees.”

The exhibition asks us to reconstitute our relationship to ecological systems. Rather than seeing them as a resource, it tells a story of ecological systems as living beings in their own right, akin to New Zealand’s decision to recognise the Whanganui River as a “living entity”.

“If we’re to reframe our minds toward how we treat the environment, and not see it as something that humans sit above, then you might start to realise that a dammed river is in a prison, or that parched trees are actually screaming for help,” says Reed. “So telling people compelling stories about the environment around them is the best way to give them agency, and in turn, help them see how they might make a positive impact on the future.”

––

Aviva Reed is an interdisciplinary visual ecologist. Her practice explores scientific theories, particularly concepts associated with evolution and the ecological imagination. Her work aims to explore time and scale using storytelling and visual aids to communicate complex scientific ideas. She invites people interested in the research tabled for HYDRO / LOGIC to contact her for more collaboration.