Bravely embracing landscape architecture without borders

Today’s challenges and stressed environmental conditions demand a new way of intervening in the landscape, and of understanding the scales of effective practice.

Recent history has seen repeated attempts to redraw the boundaries between art, architecture, and landscape architecture. The modernists invented what appeared to be an ideal model that synthesised the arts. Then their postmodern progeny countered this, with pluralist fusion. In 1979, reacting against contemporary art’s transformation of modernist medium-specificity into postmodernist medium multiplicity, the art historian Rosalind Krauss published her now seminal essay, Sculpture in the Expanded Field. Krauss presented a precise diagram of the structural parameters of sculpture, architecture, and landscape art. This was later adapted by Elizabeth Meyer in 1997 to landscape architecture. Both Krauss and Meyer sought to clarify what transformative practices are, what they are not, and what they can become, when boundaries are blurred. Such a blurring of boundaries is central to the work of Gabriella Trovato, both in her work in Syrian Refugee Camps, and her role as the chair of Landscape Architects Without Borders.

While being a landscape architect, the importance of Trovato’s work is not, however, restricted to it built outcomes. Rather, it is the techniques and methods employed in working with large scale, displaced communities in need. Twenty-first century challenges, and anthropocenic conditions, demand the expanding of our fields of operation, as well as our understanding of the scales of effective practice.

SueAnne Ware: The theme of this year’s AILA Festival is the Expanding Field, and while the phrase is inspired by Rosalind Krauss’ Sculpture in the Expanded Field (1979), I am interested in how your practice extends, or helps us to conceive of landscape architecture differently. Can you describe the work you are doing in Lebanon, in Syrian refugee camps? How do you feel it is expanding the field of Landscape Architecture and/or that of an academic practitioner in landscape architecture?

Gabriella Trovato: My work in Lebanon, working with displaced Syrians, started as an activist reaction to an emergency situation. I knew I had to act, without knowing how to do it. Everything begun six years ago, while questioning the role of landscape architects in the context of humanitarian crisis. Honestly, I’m not sure I have an answer to that question and I’m still in search of a suitable response. The work I’m doing initiated as hands-on field work and community engagement. But it is supported by a strong theoretical and research component.

The landscape architecture profession is in a state of radical change, responding to the global challenges we are facing. And the work I am conducting, as a practitioner, researcher and academic acknowledges those challenges, focusing on humanitarian design. It fits into the objectives of the Landscape Architects Without Borders – a working group of the International Federation of Landscape Architects, of which I am the chair. LAWB is committed to work with vulnerable and disadvantaged communities, especially those affected by war, conflict and natural disaster, helping them to re-create safe, sustainable and dignified living conditions.

SAW: In 2014, I visited you in Lebanon. Can you describe how the project and your practice has evolved since it was first implemented?

GT: In 2014 I was working with my students at the Landscape Department at the American University of Beirut, identifying paths of intervention, in the case of displaced populations settled in camps. An Informal Tented Settlement (ITS) was chosen in south Lebanon, Sarafand, where field-work included in situ interviews with displaced Syrians and workshops with children. These workshops allowed us to learn from the inhabitant’s way of dealing with everyday needs and problems. This in turn allowed us to seek to upgrade their environment, using our skills and knowledge. Students applied and adapted technical solutions to complex situations, considering the community’s lack of capacity and realistic possibility for maintenance. The projects were site specific and responded to precise requirements. Most aimed to alleviate the impact of the new illegal residential compounds, on the agricultural land, while making people aware of the risk the new structures will have on future environmental and productive assets in the area.

In 2015 I organised an International Landscape Operative Workshop titled ‘e-scape refugee settlement’. 15 students and 10 international professors spent eight days in Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon. During the workshop we physically intervened on the ground, and created public spaces on the open areas of the ITS, using a participatory approach.

A playground, however informal and temporary, is immediately put to good use.

Planting a garden can be a powerful act of place making.

Transforming a discarded open space into a vegetable garden, can be a powerful act of place making.

Children play in the new, improvised playground.

Children play in the new, improvised playground.

Children play in the new, improvised playground.

Working in informal settlements, with displaced communities, means hands-on project delivery.

Working in informal settlements, with displaced communities, means hands-on project delivery.

To engage with informal settlements landscape architects need to break down boundaries and embrace the temporary.

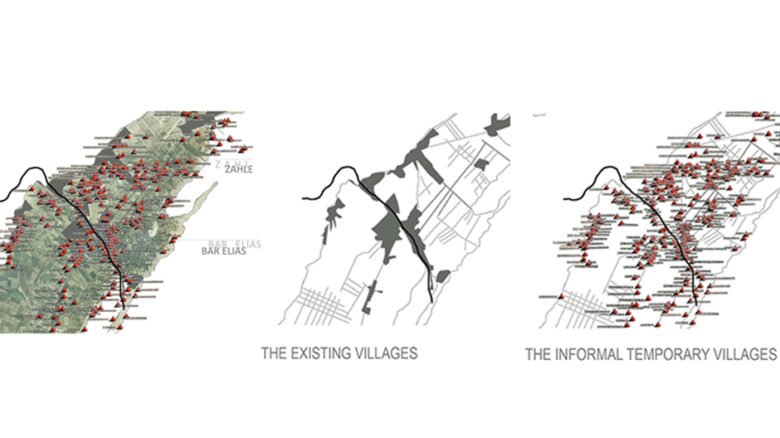

Map of existing villages and informal temporary villages in Bar Elias, Lebanon

We offered the community shaded areas, to gather during the day, with a playground equipped with simple and colourful structures for children to play and enjoy. We provided a technical solution for a pedestrian path among the tents, levelling the ground, creating a drainage channel and planting a rain garden. And we transformed a discarded open space into into a vegetable garden, using a vertical structure, and a game area for children to play with water.

A few weeks after the workshop, the owner of the land on which the ITS was built destroyed and removed all the elements that we built, with and for the community. But the inhabitants of the ITS continued the process, building new and targeted interventions at the scale of single tents and/or communal areas. During a subsequent visit to the settlement, they proudly showed us the new realised interventions and invited us to replicate the experience.

SAW: That must have been very frustrating and disappointing but also inspiring to see that the community reclaimed sites and made their own small projects. What have been the biggest challenges of working in these situations? Equally what has been the biggest rewards?

GT: The non-intervention policy is a major challenge. It is clear that Lebanon doesn’t want to relieve the daily burdens of the Syrians. They are not welcome, and they have to return to their country. Together with the religious implication of the Syrian crisis on the stability of the country, this non-intervention policy has repercussions on the spatial and social organisation and location of the ITSs, and it restricts the type of interventions that are implementable. That’s the reason why, in the past year, my work has focused more on investigating and comparing the different forms of informal settling and land appropriation, in the rural and city context. The mapping tool is used to understand the organisation of the space, and the way new landscapes are shaped under the pressure of multiple actors to respond to an emergency situation.

This helps me to explore these new realities of place, in urban and rural contexts, indicating the path to potential landscape intervention strategies that could be more efficient in the case of migration and borders condition.

We did not expect the community to be as responsive and collaborative as it was. When you are exploited and in despair, when you feel like your life is meaningless, it is possible to become irresponsive and uninterested on the future. Instead, we gained the community’s trust and many ITS residents volunteered and contributed in different ways to the final outcome. The inhabitants continued the process that was initiated by the workshop, building new and targeted interventions at the scale of single tents and communal areas. This was the most important outcome.

SAW: You are describing community resilience and also how landscape architects can invent techniques to ensure resilience. Are your methods transferrable? How might the work you are doing assist others to work with informal settlements elsewhere? Can the techniques you utilise also frame how other landscape architects work with other refugee communities?

GT: The work I’m conducting in Lebanon is based on an extensive reading and interpretation of the situation in place. A series of mapping exercises, supported by an extensive photographic campaign informs the body of the research. It allows us to delve into ordinary everyday life and the subjective experience of the space, in different typologies of informal-scapes and settlement conditions in Lebanon. The mapping exercise was farther corroborated by fieldwork, informal interviews, analysis of land-use change, landscape visual assessment, landscape exploitation and use, determined through guided walkthroughs, landscape readings and evaluations of the traces founded on site, as well as implementation of site-specific interventions, on the open spaces of one Syrian Informal Settlement on the Bekaa Valley, in Lebanon.

The latter was the result of a workshop that had two primary goals. First, to formulate a definition of community, attuned to the reality of refugee settlements in Lebanon. Second, while conducting fieldwork and learning from the informal settlement, we also sought to make a more direct contribution through the design and implementation of public space projects, aimed at enriching collective imaginary and memory.

The final product was the result of collaboration between the expertise of the landscape professionals and academics, and the deep knowledge of the inhabitant of the ITS. Realised projects were not cosmetic, or based on received prior knowledge. Rather, the design methodology was based on the inherent character of the landscape, applying that local knowledge directly in the creative design process. With these small projects we demonstrate that we can intervene on existing conditions, in an attempt to mitigate the transformation these settlements make on the land. Importantly, the inhabitants are involved in the decision-making process, from the beginning, in an attempt to encourage them to take ownership of the public milieu. Workshops, meetings and day-by-day discussions, help visiting designers and camp residents to better understand each other and to work together.

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

One year after... the International Operative Landscape Workshop, in the Al Tyliani Informal Settlement, Lebanon

SAW: You’ve been reflecting on, publishing and presenting your work for a number of years. What is your advice for landscape architects who want to work in the non-profit sector? And finally, what are the ethical and social challenging issues that this work seeks to engage with, and how do those challenges play out in the physical realm?

GT: One of the main challenges we have to deal with, while designing for displaced people, refugees or deprived communities, is related to the issue of temporality and sense of belonging. Place is an important aspect of human existence and an important source of security and identity. Places shape our memories, feelings and thoughts, and in turn people shape landscape around them, through their experiences and actions. In this way, place is also tied to culture, history and identity. Cultures are imbedded in places and lands become the storehouses of ideas.

This understanding of existing cultural elements, and their nascent meaning, should influence and inform strategies of intervention at multiple levels. Hence it is a must to focus on the interaction and communication between design experts and community members in envisioning scenarios of intervention, to address the adversity created by displacement and temporary settlement. Besides this, I advise to think small and pursue intentionally modest, considered and localised interventions that are easy to be maintained, and with a low budget and using adequate technologies. Where possible, I also advise the participation of the impacted community.

Working with displaced people entails several ethical and social issues that are common across different disciplines. As designers we are committed to work to ensure that some forms of livelihoods are re-established, that dignity and self-respect are promoted and that possible dependency culture is reduced. All of this goes hand-in-hand with the understanding and respect for different cultural roles, as a basis for every type of design intervention in a deprived community.

The most important lesson we have learned is that being sensitive to culture doesn’t necessarily mean we can avoid unintended consequences of good intentions. While we do our best not to interfere, or modify the internal stability of the settlement, involving inhabitant from the beginning, in the decision-making process, others political forces often escape our control. As mentioned, we have seen places that we have worked on, be destroyed by the local owner of the land. This left us feeling frustrated and I believe our intervention was ethically incorrect. We promised changes that we were not able to maintain, and the inhabitants were threaten by the land owner.

–

Dr Gabriella Trovato will present her work at this year’s International Festival of Landscape Architecture 11–14 October 2018, Gold Coast, QLD. Her presentation will explore how landscape architects can evolve their practices to include work in humanitarian crisis situations. She is interviewed here by Professor SueAnne Ware, Head of School of Architecture and Built Environment, University of Newcastle.