The spectre of failure haunts Australia’s city-makers. Why do they keep getting it so wrong?

Craig Allchin considers the chequered history of visionary urbanism in Australia, as captured by two recent books.

“In the old cities, renewal should rarely be drastic and comprehensive; it should rather be sparing, sensitive and cheap. Resources should go instead to building entirely new centres and cities.”

– Hugh Stretton

This quote from Hugh Stretton’s Ideas for Australian Cities establishes one of the fundamental questions that has long-plagued those who manage Australia’s urban growth: is it better to renew our existing cities, or build new ones? Stretton’s book, first published in 1971, went on to become that rare thing in Australian publishing history, almost inconceivable now: a bestseller on urban policy. That rarity, of course, has not stopped publishers from trying to repeat the feat.

The question of whether to renew or build anew forms the thematic backbone to two recent books on Australian city making. Hugh Stretton: Selected Writings, edited by historian Graeme Davison, provides an overview of the thinking of one of Australia’s foremost urban theorists. Meanwhile, Julian Bolleter’s The Ghost Cities of Australia: A Survey of New City Proposals and Their Lessons for Australia’s 21st Century Development examines Australia’s largely fruitless history of attempting to shift growth away from established urban centres.

On the whole, Stretton believed that life in the suburbs was good. He wrote that he wanted “a house of my own, where I can sit under a vine in my own backyard; a park somewhere near, where kids can kick a football; a short walk to Tom the Cheap and a local pub; an easy trip to work in the city; half an hour’s drive maybe to the beach or some open country.”

Modernist ideals dominated thinking in architecture and urban planning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Stretton published his bestseller. There were plenty of proposals for tabula rasa-style renewal of old neighbourhoods in Australian cities at this time (perhaps most notoriously The Rocks in Sydney). Many architects considered terrace housing to be slum accommodation; better to bulldoze it and replace it with modern high-rise towers surrounded by green space, ran the thinking. We now know that in most cases this didn’t end well. This historical context is important to understanding much of Stretton’s work and thinking.

Hugh Stretton: “a user of the cities, not an expert”

Stretton studied arts, law and history, and spent time as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford. He came to urban planning through his social policy interests, describing himself as “a user of the cities, not an expert.” In this way, he was similar to Jane Jacobs, another lawyer come urbanist. Jacobs rose to prominence during protests against Robert Moses’ plans for freeways through Greenwich Village in New York. In her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1961, she identified four pre-conditions for vibrant cities: high densities of population and activity; a mixture of primary uses; small-scale, pedestrian friendly blocks and streets; and retaining old buildings and mixing them in with new.

Stretton was strongly in agreement with three of Jacobs pre-conditions for vibrant cities. He advocated for mixed-use of the pre-zoning type, praising the small scale of buildings and streets in established inner city suburbs, such as Melbourne’s Carlton and Sydney’s Paddington. Concomitantly, he also wanted renewal to be sparing. He wasn’t against new additions or high densities, however. He suggested high density should be confined to the main centres, rather than in the suburbs, which is standard urban policy today. This is also sensible, given the contextual shift from Jacob’s high-density Manhattan, to Stretton’s low-density Australian suburbia.

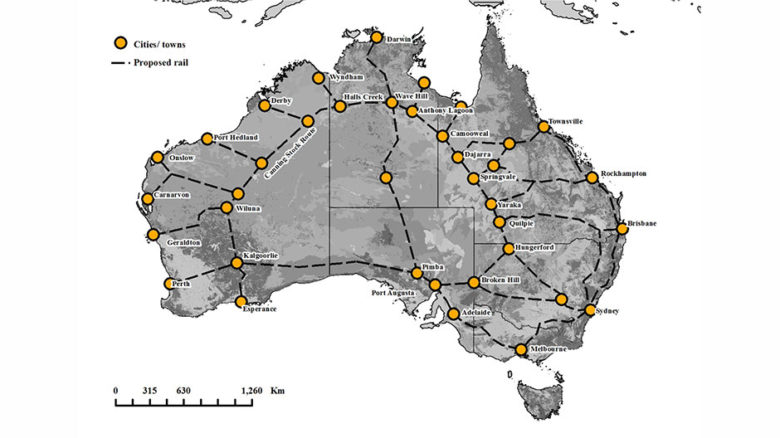

Alfred Griffiths' proposal for a ring of 17 cities inland from Australia’s coast.

Alfred Griffiths' proposed a ring of 17 cities inland from Australia’s coast.

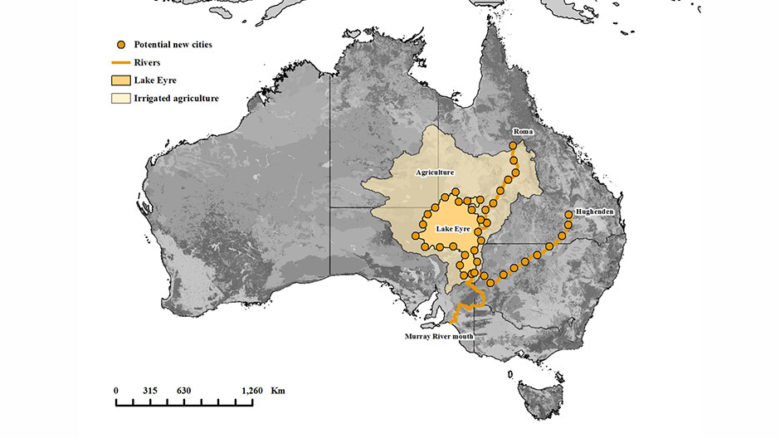

Ion Idriess's proposal to flood Lake Eyre and urbanise Australia's centre.

Stretton would, I suggest, have added a fifth criteria to Jacob’s list: demographic diversity. In the chapter titled “Who is My Neighbour?” in Ideas for Australian Cities, Stretton proposes that “socially mixed neighbourhoods are one of the simplest, cheapest and least oppressive ways of reducing the effects of other inequalities.” He described the social value of mixed suburbs as enabling “important rich-and-poor exchanges of ambition, compassion and the learning and initiative required to use whatever social services are in theory offering. From poorer neighbours, affluent children may pick up better politics, mechanical skills and social capacities than their snobbish schools offer them”.

Stretton understood the need for urban change and was advocating for much more sophisticated solutions than those otherwise on offer at the time. In “Cities as Distributors” (1976), he suggested that one million is an ideal population for a city. For populations above this, he believed cities needed multiple centres to ensure everyone had good access to jobs and services. This is the Greater Sydney Commission’s current plan for Sydney, which aims to create a metropolis of three cities, albeit the population of each will be between one and two million. Melbourne, however, is still struggling with a very dominant single centre.

The Whitlam government embraces Stretton’s ideas for Australian cities

Many of Stretton’s policy ideas directly influenced the Whitlam Government of 1972 to 1974, which proposed a range of new cities for Australia. Had they successfully realised these proposals, Stretton’s ideal cities of one million people might have been viable. As Bolleter’s Ghost Cities details, though, almost none of them ever were, and the forces of globalization and major changes in Australia’s economy have resulted in very different cities.

Australian Bureau of Statistics’ projections see Australia’s population growing to over 40,000,000 by 2060, and over 70,000,000 by 2100. Ghost Cities documents some of the biggest and boldest ideas put forward to populate the Australian continent, and manage its population growth. The title of the book alludes to the spectre of failure that tends to haunt those governments, policy makers and planners who dare to dream big. This is one of the conundrums that Bolleter recognizes, and part of the reason why this book is important.

The challenges we face in our cities are daunting, and the built environment professions need to explore big, bold solutions to solve them. But there is always the risk of failure, the consequences of which, in slow growing and very complicated cities, can be catastrophic. We need to know a lot more about what has been proposed before and why it worked – or, as in most of the cases in this book, why it didn’t.

Here, Bolleter quotes the planner and academic Robert Freestone: “Hard questions have often been avoided, fatally dumbed down or downright ignored. Big Ideas, products of their time, have advanced then retreated or just run out of puff as conditions and circumstances have moved on.”

Australia was seen as a vast and boundless country in the early 20th century. Edward Brady’s book Australia Unlimited, published in 1918, argued the continent could support up to 500 million people. This belief was based in part on the transformations he had witnessed in the USA, where the “wild west” was transformed into fertile farmland. It demonstrates a very limited understanding of the vast centre of the Australian continent and its climate, but Brady was no different from many white Australians in this regard.

Prolific Australian author Ion Idriess believed that “[w]e have in our continent an inexhaustible storehouse of all the needs of man for a million years to some. There is no lack of anything in Australia for us, and future generations. All that we and our descendants can ever need, no matter what unknown materials future advancement and inventions will call for, is all here in the raw state.”

Idriess wrote this at a time when the Garden City movement was in vogue, when it was thought that new, self-contained cities could be created almost anywhere. This thinking likely lay behind some of the bolder ideas for populating the country. One of the most ambitious of these was the post-World War Two proposal by businessman Alfred Griffiths. Griffiths wanted to open up central Australia for development by building a ring of 17 cities a few hundred kilometres inland from Australia’s coast, connected by an 11,000-kilometre long rail line.

Idriess’ proposal, however, was even more wildly ambitious. He wanted to divert water from east of Australia’s largest mountain range, the Great Dividing Range, and alter the flows of two of its most important rivers, the Darling and Murray, to vastly expand Lake Eyre and irrigate the areas around it. He believed this would allow a Garden City to grow “on the fertile plains around Lake Eyre”. Lake Eyre, a complex of normally dry salt pans, sits at the lowest point in Australia and is surrounded by desert.

Other big visions from around this time include a Garden City proposal at Mallacoota, near Victoria’s western border with New South Wales, and a Jewish colony proposed for the Kimberley, Western Australia’s vast and sparsely settled north, in 1939. These and other proposals failed for many now seemingly obvious reasons, but Bolleter also suggests that their failure was at least partly due to an underestimation of the “continuing livability of the capital cities, and coastal areas in general.”

From urban crisis to more ghost cities

As Bolleter describes, in the late 1960s a perception began to develop that “Australia’s ‘sordid’ cities were in a crisis that encompassed ‘urban ugliness, overcrowding, pathology, congestion, pollution, societal stratification, and even potential vulnerability in war.’” In response, the progressive Whitlam Government, elected to power in 1972, created the Department of Urban and Rural Development (DURD). Stretton’s ideas influenced the department’s agenda, as did the proponents of decentralization in the USA, renowned geophysicist and oceanographer Athelstan Spilhaus among them.

As Spilhaus had written, “if half the present 200,000,000 people in the US were living in 800 cities with a population of 250,000 each, and if these cities were scattered evenly across the United States, we would not have the pollution, the traffic congestion, the riots and many of the other ills that develop when cities become too large.”

The DURD developed policies to decentralize the population from Australia’s capitals into cities of two types: regional cities and satellite cities. Satellite cities were to be “developed within the influence of an existing metropolitan area but as a self-contained entity, rather than a metropolitan dormitory area.” Examples included Geelong, roughly 60 kilometres south west of Melbourne, and Gosford-Wyong, some 50 kilometres north of Sydney. It was thought regional cities, such as Albury-Wodonga on the border between Victoria and New South Wales, could reach ideal populations of 100,000 to 500,000, which would supposedly provide the benefits, but not the problems, of a big city.

In the brief life of the Whitlam Government, Albury-Wodonga was the initial focus for city building. It received 60 percent of all growth centre funding between 1973 and 1977, reflecting the fact that such projects had “overly concentrated on physical planning to the relative exclusion of economic considerations.”

Albury-Wodonga didn’t grow as expected. With a population today of around 90,000, it isn’t quite a “ghost” city, but as an attempt to grow a major regional city it is hardly a success. Bolleter describes the “centralizing economic forces” of globalization as part of the reason why the regional cities program failed. The satellite cities proposal, however, was seemingly right on the money. Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Perth are extending into 100- to 200-kilometre-long linear cities, stretched along the coast. Bolleter concludes that “without establishing new or boosted (regional) cities, population will continue to be concentrated in our state capitals, which in time will become megacities and as such their livability will be diminished.”

Perhaps he’s right in that livability as defined by Stretton will be diminished. But I would argue that life on a suburban quarter-acre block may not necessarily be what the diverse and mixed demographic of today’s cities want, nor what they can afford. The single biggest challenge for this generation is housing affordability. The young digital natives, who are hyper-connected to their friends and the world, want a more urban lifestyle. They are staying in ever smaller and more expensive rental housing in big cities; they are not flocking to Albury-Wodonga. For many, apartment living with high amenity and excellent services is preferable to a suburban block in a regional city. Or perhaps we need to explore completely new models which can capture the benefits of a quiet, suburban home in a new urban typology.

Instead of re-building our existing city models in new places, we might need to deliver new models of living in existing places – urban spaces of our own, perhaps with room to sit under a vine, a park somewhere near, where kids can kick a ball.

–

Craig Allchin is an architect and urban designer. He consults on various projects to governments and the private sector, focusing on strategies at both the macro and micro scales of the city.