Into the woods: an Easter meditation on trees

Trees connect cultures to landscapes, rooting traditions to place. In an age of unprecedented deforestation, we should remember that trees are more than the sum of their utilitarian value as timber, food, fuel or otherwise.

Whatever investment we may or may not have in the tradition, everybody knows a Christmas tree when they see one. If nothing else, the ghosts of Christmas Retail, who stir abroad these days from Halloween till Twelfth Night (both feasts of benign transgression and slipped identity) ensure that we don’t forget our iconography. But did you know about the Ostereierbaum?

The Easter-egg tree, like the Christmas tree, is a German tradition, its origins lost in dim antiquity, that sees trees adorned on every limb with painted eggs. Both are rich with seasonal symbolism: the evergreen Christmas tree’s lights a reminder that the winter darkness through which they gleam will pass; the Easter egg in tune with spring’s burgeoning renewal of life.

But an Easter-egg tree? Surely the Easter bunny serves as an apt and able dispatcher of those seasonal goodies? But there’s something about the image of the tree that resonates. It requires only brief reflection to notice how deeply embedded in the human imagination the tree stands. Few human cultures have taken hold in wholly treeless environments, and trees have figured prominently both as objects and as players in more mythologies than you can shake a stick at. Not one but two trees stand at the biblical fountainhead of the Western imagination, planted in the very heart of Paradise by God himself. It gets complicated after that, but there they are.

The later literary evidence is ample. Forests fraught with hidden depths and perils loom on every quarter, in stories both antique and modern. Dante begins his pilgrimage through The Divine Comedy in a selva oscura (‘a dark forest’). Broceliande, the faerie-wood of Arthurian myth, stands between the human world and some otherwhere of making and metamorphosis. The Forest of Arden in Shakespeare’s As You Like It is technically the Ardennes Forest in Belgium. In the play it serves as a scene of frolic and restoration, a pastoral hospice removed from the machinations of a corrupt court culture. Was any writer as tree-minded as J.R.R. Tolkien? His Mirkwood, Old Forest, Lorien and Fangorn all ground critical stages in his protagonists’ quests, affording scenes of both comfort and confrontation.

Christmas trees are conifers, like those of northern Europe. Germanic peoples have mythology rich in trees.

The largest recorded Easter Egg tree was a pecan tree containing 82,404 painted hen eggs in Brazil. March 2017

The Christmas tree is relatively modern: a German custom adopted in English-speaking lands during the 19thC.

Forests are places of wonder and horror, from the slaughter of Romans in Teutoberg Forest to WWII in the Ardenne.

In history too the forest can be a place of wonder and horror. The last Nazi counteroffensive on the western front during the Second World War, the so-called Battle of the Bulge, burst from under the eaves of the Ardennes. And miles east and centuries earlier, the Teutoburg Forest in lower Saxony saw the slaughter of three Roman legions and their auxiliaries in 9 CE by a confederation of Germanic tribes. ‘Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!’ moaned Caesar Augustus on hearing the fell tidings, addressing his general whose head by then had been staked to a Germanic tree. Elsewhere in his wide domains, another man was not long after nailed to a tree of sorts, in a provincial crucifixion that was just a bit of business as usual in the imperial justice system.

By a delicious irony, that bit of bureaucratised brutality set changes in motion which, for better and for worse, completely upended the world Rome had just about finished organising to its satisfaction. Among the modern reverberations of that upending stands the Christmas tree, part pagan fertility symbol, part poignant reminder of how the sweetness of Christ’s birth is overshadowed by his fated death on a less happy tree.

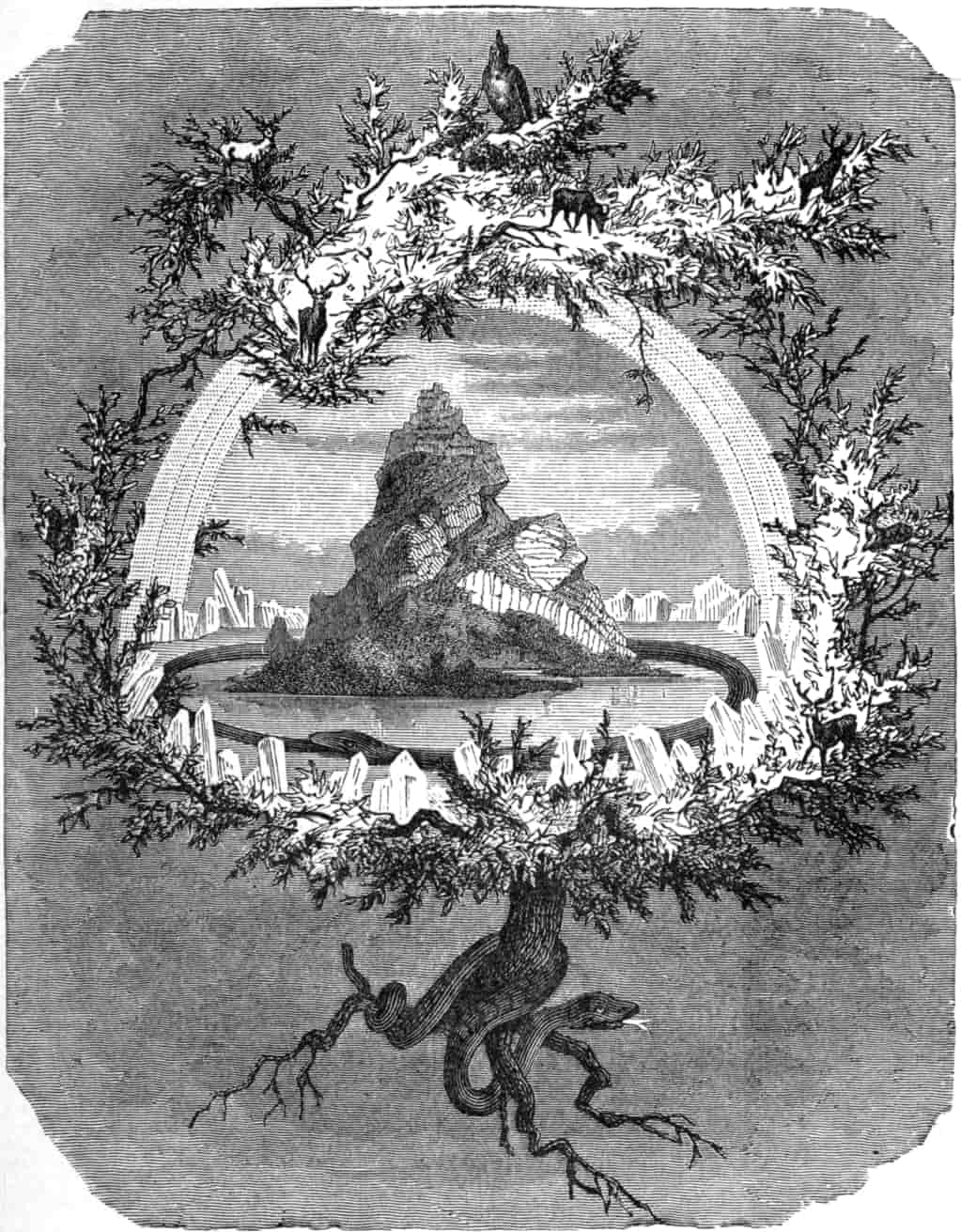

The Christmas tree itself is a relatively modern arrival, however: a German custom adopted in English-speaking lands only during the nineteenth century. It is typically a conifer of the kinds that dominate the Teutoburg forest. In one of life’s little ironies, the descendants of the peoples who slaughtered Varus’ legions composed ‘O, Tannenbaum’. All the Germanic peoples seem a bit tree-struck. Their old deity Óðinn/Woden/Wotan was said to have endured a quasi-shamanistic ordeal, hung on a tree for nine days, pierced by his own spear, as a sacrifice to himself. His sacred groves at Uppsala occasionally bore up the bodies of other sacrificial victims. Nothing by half-measures, and a far cry from more traditional tree-adornments.

The Christmas tree, however, is something else yet again. Break it down to its structural components: the tapering cone-shape, sheathed with light; star or angel above; gifts strewn in a circle around its base. The light of every star that reaches us forms a cone that takes the earth as its base and the point-source we see in the night sky as its apex. A cone stretched to the fineness of a needle, but geometrically a cone nonetheless. Poignantly distant and bright at its tip, abundant at its base. The visit of the magi to Bethlehem begins with a star and ends with the bestowing of gifts. The most banal shopping-mall displays, thrown up in early November and comprising no more than petroleum derivatives confected into glittering abstract cones and triangles, still bear the imprint of this elemental vision.

The visit of the magi to Bethlehem begins with a star and ends with the bestowing of gifts.

Tapering cone-shape, sheathed with light; star above; gifts in a circle around its base. Taiwan shopping Mall tree.

Few human cultures have taken hold in wholly treeless environments. Are cultures weakened when they lose trees?

An extraordinary dream-vision narrated by an anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet of the eighth or ninth century CE records an analogous spectacle:

It seemed to me I saw a glorious tree,

thrust into the sky, intensely bright,

wound about with light. All of that sign

was covered with gold and gems whose light flashed forth

to the world’s end, five upon the crossbeam.

All God’s angels, created forever fair,

gazed on it there. That was no gallows

for a felon, for holy spirits and men

across the earth were contemplating it there,

the whole of this majestic universe.The Dream of the Rood, ll. 4-12 (here and below, my translation)

The ‘rood’ of the poem’s modern title is the cross (Old English rōd) of the crucifixion, which, after the poet’s visionary preamble, tells in its own voice how hostile men had seized it from its forest roots and compelled it to serve as an instrument of judicial torment. In its first appearance to the dreamer, however, it shines like the mother of all Christmas trees, a cosmic axletree oddly reminiscent of the Old Norse world-ash Yggdrasil, whose roots reach down into hel, the region of the dead, while its topmost branches touch the realms of the gods. The rood’s splendour overlays its grisly career as a torture-engine. The dreamer must untangle the fearsome parallax of his double vision, which weighs on his own spirit:

But underneath the gold I could perceive

the long-ago torments of miserable men.

First it began to bleed from its right side,

and I was utterly racked by many griefs

and fear, in front of that beautiful sight. I saw

that blazing symbol change its raiment and hue:

sometimes it was soaked with flowing blood,

completely drenched; sometimes adorned with treasure.(The Dream of the Rood, ll. 18-23)

In an almost incomprehensibly extreme polarity, the tree of the poet’s vision embodies the loftiest exaltation and the most abject oppression that incarnate existence can bestow on human or tree. The genius of the poem is to fuse the two and, for once, in a stunning reversal of agency, to let the tree speak on behalf of the human. William Langland, in his fourteenth-century Vision of Piers Plowman, allows another dreamer a gentler vision of the same dynamic:

And also the plant of peace, of virtues most precious,

for heaven could not hold it, it was of itself so heavy

till it had eaten its fill of earth,

and when it had drawn flesh and blood from this ground,

there was never thereafter a lighter leaf on the linden-tree

as nimble and piercing as the point of a needle,

that neither armour nor high walls could hinder its passage.(Piers Plowman, I.152-158)

This wholly allegorical ‘plant of peace’ descends from heaven, drawn earthward by its weight like a self-seeding tree. From the earth it takes ‘flesh and blood’, an allusion to Christ’s incarnation and its subsequent restoration of the fallen human constitution. Langland realises this in vegetal imagery that evokes the paradoxical lightness the plant takes from its commingling with earth’s own weight and substance. This celestial plant of peace falls to earth only to spring heavenward again, light as a feather yet utterly irresistible, bearing our earthly nature with it.

These are only a few examples, drawn from readings in medieval literature, of how the image of the tree has wound its limbs around our collective imagination. Can such imagery afford us moderns any clearer sense of our intimate entanglement with the realms of growth and fruition now imperilled by anthropogenic climate change? Perhaps. Perhaps they can help us take fuller measure of our peril. Tolkien dramatizes how raw power, wielded for its own sake, violates the living world in its industrial-scale poisoning of air, water and earth in the wastes of Mordor and elsewhere in his fictions. Is the ethical, rhetorical and environmental wastage of late capitalism any less confronting?

How do literature and the so-called ‘real’ world intersect? Which are more real, the trees of botany, horticulture or carpentry, or trees such as those considered here? Depends on who’s asking and from what perch, but at our present historical moment we need to maintain the widest and deepest perspectives we can. When Jakelin Troy observes, in another context, ‘[w]hen we destroy trees, we destroy ourselves. We cannot survive in a treeless world’, she speaks of much more than simple physical necessity. Yes, we need the green world to act as a carbon sink, to feed us and to provide amenity for otherwise barren urban landscapes, but such instrumental logic is the symptom of an underlying pathology. The ideals of stewardship maintained in many of the world’s indigenous cultures, which western modernity has largely abandoned, call to us more urgently than ever. The literary record sustains and emphasises Troy’s quiet assertion that trees are our fellow beings and deserve respect as such.

Think big. As physical presences, trees (and all vegetation, really) brace heaven and earth. They call down light and use its energy to stir dead matter into living forms that serve and nourish all other life on this planet. Yet their limbs and leaves crowd our interiors as well.

Entering a dark wood as Dante and many of Arthur’s knights did, most of us will sense dimly that something’s in there, just as our waking consciousness itself can overhear a presence somewhere behind our breasts and faces that we speak as ‘I’, whose depths are vaster than we will ever know as a matter of mere fact. Those depths may prove full of terrifying spectres, or of howling Alemanni charging to thrust our imperial pretensions from their demesnes. But like all trees, we are called to stand between the high and the low (conceive them as you will) and in our thoughts and imaginations to allow those polar extremes to fructify each other in our centre. To diminish those avatars of our inmost ecology as so much stuff to be cleared or processed for profit is to flay our own souls and sell their pelts as fashion accessories.

–

Robert DiNapoli is a scholar of English language and literature, a translator and essayist. He has lectured on English-language poetry of all periods at universities in North America, England and Australia with a focus on Old and Middle English poetry. His forthcoming book of poems Engelboc, explores frontiers between language, history, memory and the evolution of spiritual sensibilities across time.