Sound in the City: Translating Ambiance

A group exhibition at Yarra Sculpture Gallery curated by Dr Jordan Lacey asked artists to respond to ‘translating ambiance’. Tracey Clement spoke to Lacey about the power of sound, using galleries as research laboratories and the value of bringing the sounds of nature into the city.

Tracey Clement: You are a musician and sound artist who taught for many years in high schools. What made you first consider that sound had something to contribute to urban planning?

Jordan Lacey: It’s really me joining a conversation that has been taking place for about 40 years, but has only just started to gather steam. I went back to university in 2008, at RMIT, and while I was there I came across soundscape studies in the School of Architecture and Design. Soundscape studies has a history stretching back to the mid-1970s in which artists, primarily composers, became concerned about the growing noises of the city and proposed this idea of soundscape design. So the discussion I’ve joined is very much about how can we as musicians, composers and artists step into the question of how our cities sound. And how should they sound?

Noise is an issue for many people in the urban context. Traditionally we have tended to talk about noise attenuation, but it is not always possible to attenuate or remove noise. So what are other creative ways that we can think about designing or transforming, or in the case of this project translating, the sounds of the city so that we can create rich and varied experiences and encounters? And for me that is where the artist steps in as potentially an integral and important part of that conversation.

Tracey Clement: So why do you think artists might have something to contribute to this field?

Jordan Lacey: Artists are masters of transforming or reworking materials thereby creating new experiences, that is what they do. I see sound as a material, so it is very natural to me that artists could contribute. Designers and planners, obviously they do an amazing job, but their results are determined by codes, whether they be building codes or policy codes. Artists have a unique ability to think outside of codes, or to challenge codes, and maybe that is what we need if we are going to diversify the experience of inhabiting the city. But certainly I am not an advocate of plonk-art. I’m not interested in bronze statues of old conquerors. Public art that is done really well, and that is really interesting, I see it as potentially a great entry point to how urban design and artistic practices can fuse. It seems to be the meeting point.

Tracey Clement: That makes me think of Linda Tegg’s Grasslands piece outside the State Library of Victoria in which she planted hundreds of native grasses. It is a public artwork that is very much a landscape intervention…

Jordan Lacey: That’s an excellent example because it goes right into the heart of what this research is trying to do: it is investigating the area of biophilic design. (That’s bio for life and philic means love.) It was put forward by a biologist in the mid-1980s who claimed that we had a genetic predisposition towards a love of nature. That has all but been dismissed in that so far no such gene has been found. Remember the 80s? It was all about the genes? But what has continued or grown out of that is this area called biophilic design, and it is very much an area inhabited by landscape architects and architects and what they are arguing is that if we can introduce nature into cities then we can create happiness, health and well-being. So I stepped into this discussion and I’m saying I agree with this, but maybe there is another way to think about biophilic design rather than just trying to recreate nature in the city. Maybe there is a way that we can try and understand its ambiance via the body; and then we can somehow translate that feeling or atmosphere into an urban context.

Hydrophone recording in preparation for COLD Photo: Jordan Lacey

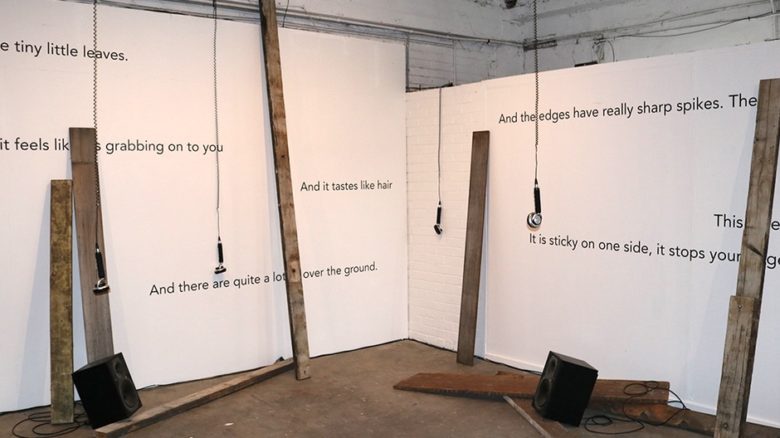

Exhibition. Lisa Hall + Salome Voegelin - And it Tastes Like Hair Photo: Jordan Lacey

Exhibition. Jordan Lacey - COLD Photo: Jordan Lacey

Tracey Clement: Both your current group show and your broader DECRA (Discovery Early Career Researcher Award) project are called Translating Ambiance. Tell me about your use of the phrase ambiance…

Jordan Lacey: Well there are obviously two spellings of the word. So there is ambience which I probably associate most with Brian Eno’s ambient music. And ambient music, Eno tells us, can be encountered in two simultaneous ways: it can be something that we push to the background of our attention and hardly notice, while in the same instance we can actually draw it in and it becomes very present. But ambiance, the French spelling, is a growing field of research that developed at CRESSON, a French institute that roughly translates to ‘centre for research on sound space and urban environment’, which has parallels with atmosphere theory developed in Germany by the philosopher Gernot Böhme. It developed at the Grenoble School of Architecture and Design in the 1970s; a really fascinating place.

The most recent leader of that group has been Jean-Paul Thibaud, and he’s the one who has really pushed ambiance theory. Ambiance theory is essentially trying to rethink the way that we encounter the city, or design the city, or do research in the city, from the perspective of our perceptions. So the question of design and intervention becomes how can we open up perceptibility? How can we engage with our bodily senses?

Tracey Clement: But we have five senses. In addition to hearing there is sight, touch, taste and smell. So do you think sound has something unique to offer in evoking ambiance? Is it more powerful than the other senses?

Jordan Lacey: I think that they are all equally powerful; I think that they work in tandem or in relationship with each other. But what I think is particularly powerful about sound is that it always surrounds us. It is always present and we can never switch it off. Even profoundly deaf people can feel sound, as it is also haptic. However, there is growing awareness that listening practices can forget the needs of the deaf, and this needs to be attended to. But without question, for most of us, sound is always affecting our mood and our sense of being in the environment. So it is quite capricious. But that also makes it a powerful design medium, or a powerful tool for creative play, because it can be so easily shaped and transformed.

Tracey Clement: Let’s talk about how you do that in your work. One of your stated aims is to translate the ambiance of a wilderness environment into an urban environment…

Jordan Lacey: I think when we are in the wilderness there is a sense of being alone, and falling deeply into that experience in an embodied way, that, certainly for me, can be quite restorative or uplifting. Of course it would be unrealistically optimistic to say that we would be able to exactly recreate that in an urban context, but I guess the mode of experimentation is that if we can find a way to understand how those bodily experiences are occurring through an understanding of the ambience or the atmosphere that exists at that moment, maybe that becomes the beginning of a language or a toolkit that we can start to apply in small scenarios in the urban environment.

In Translating Ambiance I’ve installed my work, Cold, in the laneway outside the gallery. I took field recordings in the Bogong high plains, Taungurung country. I used an ambisonic microphone to capture a three-dimensional recording of the environment, and hydrophones dropped into eddies in a little river to get sounds of gurgling water. In the laneway I’ve placed four air conditioning units in the exact same position as the eddies I discovered, and I am playing back the recordings through them. But obviously the recordings take on the metallic resonance of the air-con shells. And I have collaborated with a young artist called remi freer who works with lighting. So we have used lighting and synchronised it to the sound of the hydrophones to try to recreate the light and the sound ambience that captured my attention in the hills, but in the urban context of the laneway. What affects it will produce in audiences, obviously I can’t determine. It’s my first step in a number of experiments to come.

Tracey Clement: So are you trying to breakdown the wilderness versus urban dichotomy?

Jordan Lacey: Definitely. I mean traditionally soundscape studies can be connected with acoustic ecology. And acoustic ecology was very much of the older environmental position that the urban was noisy and bad for our health, and nature was silent and good for us. And I do challenge that dichotomy because, obviously, nature is often full of parks, toilets, roads, boundaries and borders like the urban. And the urban is full of trees, birds and humans. And both spaces have weather and sunlight and sound. So they have more in common than there are differences. And what we are calling wilderness areas were (and in cases still are) home to indigenous people for millennia. We tend to think of wilderness as wild, uninhabited and untouched, which is, in itself, untrue. But at the same time, I do think that those spaces can produce bodily effects that are difficult to find in the city.

For me it’s more a question of diversity versus homogeneity. I talk about this in my book, Sonic Rupture (Bloomsbury 2016). What nature, or the nonhuman if you like, is very gifted at is creating diversity. And I think, primarily because of building codes and planning codes and so forth, our urban spaces globally are becoming increasingly homogenous. And there is a danger in that because humans need diversity. And maybe it’s possible through translating the ambiance of the wilderness, to create diversity; create new types of encounters in the city that speak to other ways of being human that is not just as functional economic units. How to achieve this is the type of knowledge I’m hoping to gather through this research and group show; knowledge that I hope other artists, landscape architects, designers and so on will be able to apply. Because there is something about the ambiance of wilderness, that for me at least, can evoke really needed restorative experiences.

Tracey Clement: And is that what you are hoping that people will experience within your work?

Jordan Lacey: Well, I don’t know what they will experience. It’s like the art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud says, for him translation is an important artistic tool, but he also says something always gets left behind in the translation. And we always have to remember that when we translate we are creating something new and unknown. But the point is that we are creating something new and unknown.

–

Translating Ambiance features sound works by Polly Stanton/Byron Dean, Bruce Mowson, Martin Kay, Camilla Hannan, Jordan Lacey/remi freer, Salomé Voegelin/Lisa Hall, Michael Graeve, Andrew Goodman and Catherine Clover. Yarra Sculpture Gallery 117 Vere St, Abbotsford, 5-22 September.

Dr Jordan Lacey is a research fellow at RMIT University. He has curated the group show, Translating Ambiance, as part of his broader research project which seeks to find ways that artists, especially sound artists, can bring the positive effects of the wilderness into urban space.

Tracey Clement is an artist and writer based in Sydney, Australia.