Can children be free in a city?

Fear and anxiety have come to define contemporary parenting. In this environment, allowing children to move freely about the city can seem irresponsible. But, as Karen Malone writes, if we don’t allow our children some degree of independence, their mental and physical well-being will suffer.

It is 2005 and I am on my first visit Japan. It is Autumn, a brisk afternoon, and I am on my way to a meeting. Walking along the crowded streets of Tokyo, I come on a group of kindergarten-age children. The brightly coloured school bags and hats tell me they are likely on their way home from school. Oblivious to my presence, they busy themselves picking up autumn leaves, straddling low brick curbs, swinging clasped hands, skipping, chasing, chatting and laughing. There are no adults supervising, no walking school bus conductor, no older siblings.

As a parent, I feel a sense of foreboding. I worry about their safety. Eventually, though, I have to head on and leave them to their meanderings. When I arrive at the meeting, I recount my experience to my Japanese colleague, explaining my worry that there were no adults watching out for them. He is a little taken back. “What do you mean, no adults? There were the car drivers, the shopkeepers, the other pedestrians – the city is full of adults who are taking care of them!”

This was not a one-off event. I am told most Japanese children walk to school by the time they are six years old. They also walk together after school to their local playparks to play until dark. In Tokyo alone there are 270 adventure playgrounds and thousands of small green pocket parks for children in their neighbourhood environments. Later that afternoon, I wander into a playpark close to the hotel to find young children busy climbing trees, jumping off shed roofs, stringing nets, building with wood and cooking on fires.

Japanese children playing unsupervised in city adventure play parks

Japanese children playing unsupervised in city adventure play parks

Japanese children playing unsupervised in city adventure play parks

Several years on, I returned to Tokyo to research Japanese landscape architecture with Professor Isami Kinoshita. We held focus groups with parents, who told me that they did worry about issues relating to strangers, traffic and children being lost, just as Australian parents did. To ensure their children are safe and to overcome their own fears, though, they have developed a range of strategies with children, other parents, the business community, the city mayor’s office and school administrators. They tell me that children need to be able to move freely around the streets to grow up properly and that the more they do it, the more competent and resilient they become. For that reason, parents in Tokyo are committed to continuing to find ways to make their city child-friendly.

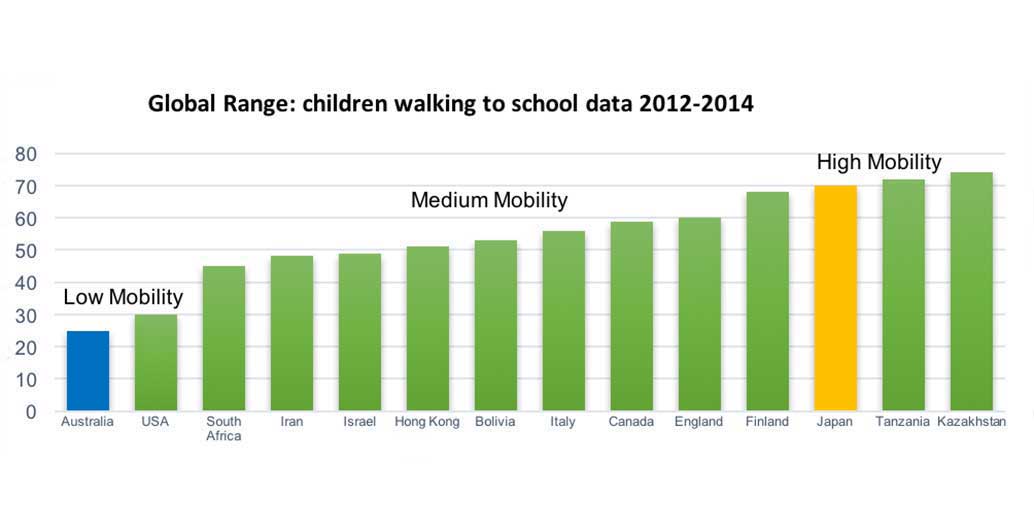

The term studies use to define this opportunity for children to move freely around their neighbourhood without adult accompaniment is Children’s Independent Mobility (CIM). Whether children are walking to school by the age of 10 is a core indicator often used to compare CIM between different city sites. The following graph provides a snapshot of children’s independent mobility in 14 countries around the world — Australia is marked in blue, while Japan is marked in yellow. The graph emerged from a study by myself and Julie Rudner, an urban planner from Latrobe University, where we analysed research evidence available on CIM in the period 2012-2014. As you can see, Japan’s children enjoy more than double the amount of independent mobility than that of Australian children. Australia, in fact, has the lowest rate of CIM of all the countries surveyed. While these comparisons are only a snapshot and do not illustrate the fine-grain differences that are evident across one city or neighbourhood, they do raise important questions. How can children’s freedom to move be so different from one country to the next? What are the key causes of these differences? What can we learn from these differences so we can design cities that support children’s freedom?

Source: Malone and Rudner 2016, http://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789812870346

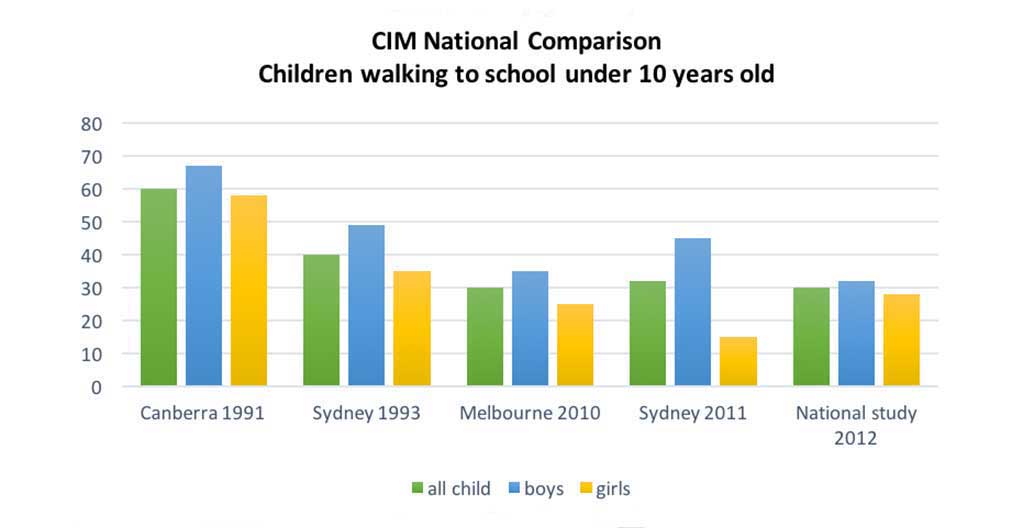

Source: Schoeppe et. al., 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2015.1082083

What we found in the global study was that in low GDP countries, such as Tanzania and Bolivia, it was commonplace to see children, especially from poor communities, actively moving around cities alone or with other children, either walking or using public transport systems. But for most developed nations, it was less common; even when children walked to school, which on average half did, they walked with a parent. There were exceptions to this, with high income nations like Japan, Kazakhstan, Finland boasting high levels of independent mobility. In Australia, where the environment is much less congested and hence seemingly more child-friendly than many countries in the world, children seldom walked alone in their neighbourhoods. On average, less than half of 10-year olds around the country are able to walk to school alone, and even fewer move freely in neighbourhoods or play in public spaces without parents. A mapping of several studies conducted in major Australia cities from 1991-2012 reveals the percentage of children walking to school has rapidly been decreasing over the past 20 years, particularly for girls.

What do Australian parents think about children’s freedom?

Recently, at a seminar in Sydney on children in the city, I asked the adult audience to recount those moments from their childhoods when they were free from adult supervision. The majority recalled playing outdoors with other children: “I had some bushes where I would play and hide with my brothers and sisters and sometimes friends” (Wilma, aged 43); “My friends and I would go to this vacant lot and build our own cubbies” (Richard, aged 36); “There was a playground at the end of our street and I would go there to play” (Catherine, aged 27); “There was a creek near our house and we would go and search for tadpoles, I wouldn’t go home ‘til it was dark” (Mark, aged 31); “We used to get all the neighbourhood kids together and go out on the street and play cricket” (Andrew, aged 39).

Tim Gill, author and play commentator from the UK, would describe the parenting styles reflected in these memories as “benign neglect”. For many growing up in baby boomer suburbia in high income cities around the world, benign neglect was the quintessential parenting experience. Being left to roam and move freely with other children, these children were self-reliant, independent, confident, physically active, competent, good risk assessors and came to know how the city ticked, its positives and negatives. The people, animals and plants they shared the city-scapes with all became part of how they came to view themselves as living in the world.

Many who are now parents themselves were surprised by their own parent’s laissez-faire attitude – “Actually, sometimes I think back and I can’t believe my parents let me do the things we used to do” (Richard, aged 36) – although they acknowledged being free mean they learnt a lot about themselves and their cities. Building on this, I then asked them to consider if they would give the same freedoms to their own children. They all said no. Typically, they answered with some variation of: “I would love to let my kids play outside, but I just can’t trust other people, there are just too many dangers these days” (Sara, aged 38).

What were the greatest concerns parents had about giving children freedom in the city? Fear of strangers and children being abducted; lack of community connectedness with a subsequent loss of social trust; and finally, a shortage of vibrant, child-friendly neighbourhood spaces.

Fear of strangers

Many parents today believe eternal vigilance is their only defence in keeping children safe. Even though crime rates reveal it is highly unlikely a child will be taken by a stranger in public, anxious parents produce bubble-wrapped children and immerse the family in a tense war of fear with city environments. Children’s play spaces in a fearful city become largely internalised or highly regulated playgrounds, where parents can vigilantly monitor potential dangers and risks. Children are seldom allowed to explore these environments on their own. Andrew (parent, aged 39) provides a typical response of a vigilant parent: “I want to let my children play freely outside and I wish we could. I know the chances are slim that something will happen but I just couldn’t forgive myself if something did happen. I have no choice to only let them play outside if I am watching them, so that only happens on weekends, when we have some spare time.” These fears are amplified by media hype, policing regimes and in recent times by risk averse government policies based on unfounded research about children’s risk assessment capabilities. A parenting model of eternal vigilance places parents directly responsible for children’s vulnerabilities and freedom.

Lack of social trust

Research shows that the most significant social determinant for increasing children’s independent mobility in cities is building local community ties and social trust. If there is a shared view of childhood and parents are confident other adults in the community will look out for their children should they need help, then they are more likely to let children outside to play. Unfortunately, social trust in many Australian cities can be thin on the ground. A heightened fear of strangers, more diverse communities and families not spending much time getting to know other families in the community, because their children go to schools or leisure activities outside their neighbourhood, all contribute to this problem. In poor communities in low income nations, support from other adults outside of the immediate family is critical to the functioning of children’s everyday lives. Parents seek support from neighbours, extended family, local shop owners, even bus drivers to watch out and care for children. Absent in my view of children in Tokyo were the invisible threads of social trust reaching out and supporting the children in the streets. If that social trust isn’t embedded in the culture of a society, a community norm, then families need to build those connections themselves. With busy lives and families often living away from extended family and friends, a lack of social connections becomes a significant factor impeding children’s freedom.

Child-friendly neighbourhood spaces

To get children out into the streets, do you start with great places and hope that children and their parents come, or do you work on getting communities outside first? Throughout the 1990s in Australian cities, city councils started dismantling neighbourhood pocket parks, especially as play safety guidelines became stricter and they opted to use limited resources on large regional parks and leisure facilities (waterparks, skateboard parks, sports arenas…). Without suitable parks within walking distance of their homes, children now needed to persuade busy parents to take them to parks for a special event, usually by car. Recently, due in part to lobbying by landscape architects, urban designers, parent groups and play researchers, the trend in play park development is moving back to investing in neighbourhood parks. The question is: can parents now be persuaded to loosen the reigns?

_

Karen Malone is Professor of Sustainability and director of the Centre for Educational Research at Western Sydney University. She will be speaking at Foreground’s Cities for Children forum in Sydney, Friday 28 July – click here for more information or to secure tickets.