Trains have always catalysed new towns and column inches. Australia’s HSR is no exception

A $200-billion development proposal to build eight new cities as part of a high speed rail network may have fired up op-ed writers, but is likely to be “politically boycotted”.

Every federal government since 1984 has considered different versions of a high speed rail (HSR) network along the eastern seaboard. The most recent comprehensive study, undertaken by a consortium led by AECOM in 2011, projected a total cost of $114 billion. Inevitably, the talkback radio burned for a few weeks, before the idea was consigned, yet again, to the archives. Until now that is.

A recent plan published by the Consolidated Land and Rail Australia (CLARA) proposes a HSR line connecting Sydney and Melbourne via Canberra. As a private investment group, CLARA’s plan differs radically from previous proposals, in that it proposes to fund the rail link through the development of eight inland “smart cities” alongside the rail line. It’s the largest “value capture” initiative ever proposed by a commercial developer, and once again has stirred columnists and commentators into action. CLARA’s plan, however, has one big problem. It directly contradicts prevailing political assumptions as to where the rail line should run. Failing to rejuvenate existing regional towns, instead CLARA’s investment lies primarily in entirely new cities. This is not what government wants.

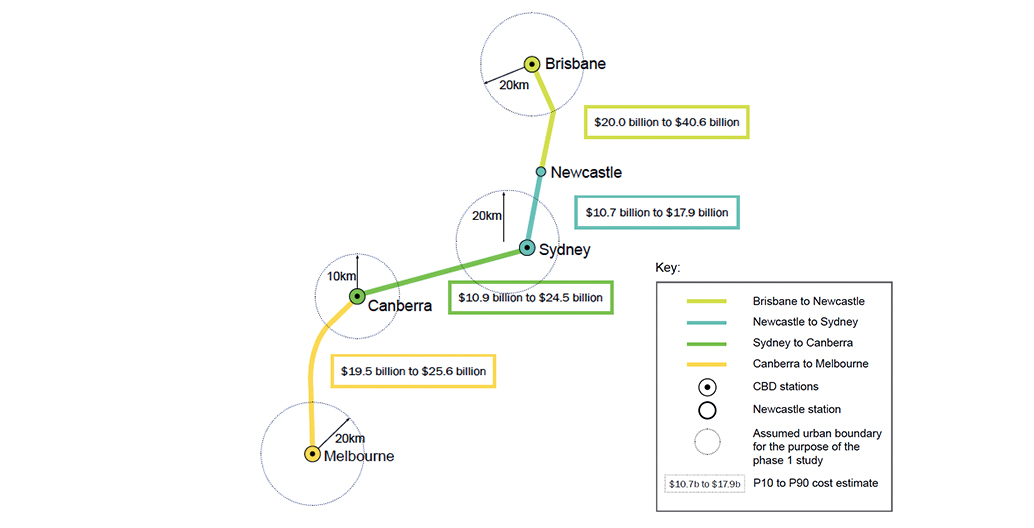

AECOM’s 2011 HSR Phase 1 Report, which identified corridors and station locations, outlined the route as “four capital city stations, four city-peripheral stations, and stations at the Gold Coast, Casino, Grafton, Coffs Harbour, Port Macquarie, Taree, Newcastle, the Central Coast, Southern Highlands, Wagga Wagga, Albury-Wodonga and Shepparton.” That’s approximately 1,748 kilometres of dedicated route between Brisbane-Sydney-Canberra-Melbourne, and is significantly different to CLARA’s proposed route.

When asked by Foreground to comment on the CLARA proposal, the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development said that, “The Australian Government is aware of some media coverage of a concept for a HSR line and regional cities proposed by the Consolidated Land and Rail Australia organisation, but has not been provided with detailed information or a proposal by CLARA.” That is to say, no comment.

Peter Newman, Professor of Sustainability at Curtin University and a former member of Infrastructure Australia, is unconvinced that CLARA’s proposal is a desirable vision for a new HSR network. “You can make these new towns, which will likely attract quite a bit of financial sector interest, but it would be more desirable to regenerate existing regional towns that are in need of investment,” Newman told Foreground. “It’s just not politically attractive. If a HSR avoids existing regional towns, it is likely to be politically boycotted.”

Newman is a keen advocate for the use of trains to centralise development as he notes that urban densities typically evolve near train stations. This is among a number of benefits that a HSR network can provide to communities and the economy.

“Cars and roads scatter development whereas trains focus it, which is what we need. All these trains will be electric and powered by solar because solar energy at stations will be recharging the system and that’s clearly the way of the future,” he said. “This is a nation building exercise that will bring a lot of employment benefits and economic advantages. But in terms of urban planning outcomes alone, trains deliver what most planners are trying to achieve.”

Risk-adjusted cost estimate ranges for study area segments image: AECOM 2011

Boundary of short-listed corridors Image: AECOM 2011

CLARA's preferred HSR route 2017

While the CLARA proposal has political challenges, in choosing a route that is significantly inland, it also has the very big geographic problem of lacking water accessibility. Professor Edward Blakely, founder of the Cities Leadership Institute at the University of Sydney, believes the proposal is on the right track in its approach to creating better peripheral cities, but access to water could be a deal-breaker.

“The farther you get away from water the less likely people are going to choose to live there. The CLARA proposal is really dependent on making interesting cities but it has to overcome Australia’s preoccupation with water. Creating new cities is problematic when we don’t have enough water available for city operations. We are not like Europe and the US where there are rivers running everywhere,” Blakely said.

If politics and geography are both a problem for CLARA’s plan, it appears that the financing is not. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s commitment to building a fast train network between Melbourne and Sydney was recently boosted by a bipartisan committee which recommended that the government should invite proposals for a HSR line and examine value capture as a way to raise private capital. This kind of cost-recovery of public investment in infrastructure, through proceeds from an increase in land value, is high on the government’s radar following a paper on alternative financing by Infrastructure Australia in 2012 – 2013.

As a co-author to that report Newman says, “Governments everywhere are shrinking in their ability to fund these incredibly expensive projects but they all need them. They have to develop partnership projects with private financiers as there is plenty of capital around while government capital is restricted.”

Even if government had the money to go it alone, Newman doesn’t believe that would necessarily be ideal. “Governments funding rail infrastructure entirely does not lead to optimal solutions. You don’t get the best land developments around stations. More often the results are ‘A to B’ projects surrounded by parking, which is not very attractive. But if you get land developers to help pay for the rail infrastructure then the property developments have to be as close as possible to the station, which means you also get really good town centres out of it.”

Value capture, conceived as clipping the ticket on land value uplift, represents a one-off gain for governments and is only one part of the HSR puzzle. Governments also need a sustainable long term investment model to help fund the rail network’s operations. This can be achieved, claims Blakely, by leasing the train operations to consortia who can then build commercial and residential units from which value capture can be harnessed over the long term. Australia, says Blakely, should be taking notes from the Japanese model.

“The train stations in Japan are as big as 10 percent of one of our CBDs. The stations have apartment housing, hotels and universities. When you get off the train, the taxi that pulls up has the same name as the railroad company. The hotel you go to is one of three or four that the railroad company owns. They even own the Starbucks,” says Blakely.

“The value capture comes from operating facilities associated with the line. This is the model that formed the basis of the US railroad. Railroad companies were given land, then built towns around them, and that’s how they made their money.” As Blakely observes, “They didn’t make their money on the railroad. They made their money on the towns.”

The question remains to what extent such large-scale, potentially transformative urban initiatives should be driven by investment models. Architect, urban designer and City of Sydney councillor Philip Thalis is cautious.

“HSR should be considered as more than an engineering or property investment challenge driven by the limits of a reasonable commute to Sydney or Melbourne. It must be a fundamental part of the national population strategy,” says Thalis. “Conceived as a value capture speculation then building an urban plan around that is the wrong way around. We should plan broadly in the nation’s long-term interest, then use value capture to help realise that vision.”

For Thalis the problem with value capture and conventional cost-benefit analyses is that the timeframes are too short. “Much of today’s urban development is on the back of railway lines dating back to the 1860s,” says Thalis. “Yet this extended payback of fixed assets is instead yoked to short-term private investment models that are entirely inappropriate for long-term city building.”

Long-term planning is certainly needed if Australia is to accommodate significant population growth, which is estimated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics to rise to nearly 50 million by 2061. As Thalis asks, “Why don’t we have a national population strategy with a positive agenda for new towns? It’s a question well argued by Richard Weller and Julian Bolleter in their book Made in Australia: The Future of Australian Cities. Yet the last time we attempted to bring together new town development and population growth was probably when the Whitlam Government established the National Growth Centre at Albury-Wodonga in 1973.”

Whatever its drawbacks, the current political focus on HSR may be inching closer to a viable plan thanks to the government’s appetite for investment partnerships. Newman believes that once the government shows that it can be done once, then everybody will feel more optimistic about tackling such projects in the future.

“The actual financial contracting process in the end is quite easy but how do you bring together planning, transport, finance and environment into one kind of group that can do the negotiation and help the procurement process to happen? They need a properly trained executive group,” he said. “Something that cuts across governmental agencies. These are partnership projects and they don’t work well if you have siloed approaches. That’s the biggest issue and one that needs to be trialled and demonstrated and then everybody will say, “This is pretty easy, we can do this.””