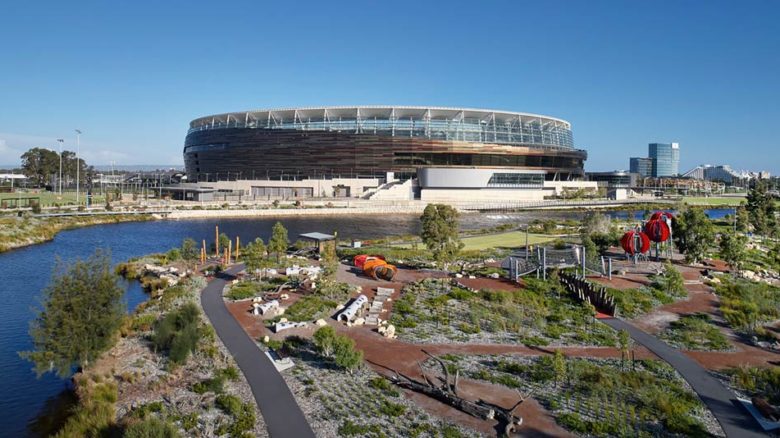

Stadium as urban catalyst: can Optus Stadium Park revitalise Perth’s Burswood Peninsula?

Perth’s new massive sports and entertainment precinct is a 60,000 capacity stadium on an isolated peninsula, with limited car parking. But this last fact is an intentional effort to change the way Perth locals use public transport and think about their city.

Across the Swan River from Perth’s CBD, the Burswood Peninsula has long been primed for renewal, despite containing plenty of challenges: contamination, unstable ground conditions, and relative isolation. Combine this with a raft of big ambitions, in particular for the precinct to function as a transit oriented major sports and entertainment hub, and you have the bones for a major city-shaping project with a lot at stake.

According to Anthony Brookfield, principal at Hassell Studios, the peninsula and nearby Riverside in East Perth are strategic development areas. With Hassell working closely with the Westadium consortium, there was a collective understanding of how this important site would develop into the future, seeing the potential for this to become a true city-shaping project.

“It was a great opportunity – because of its siting, and also because of its spaciousness,” says Brookfield. The 41-hectare site shuns the mono-functional sport precinct model in favour of a many-layered parkland positioned to act as both significant sports and entertainment destination and every-day community hub. It also sought to achieve critical benchmarks in brokering cultural change away from car-reliance towards alternative transport systems, which was a critical aspect of the brief.

“From an innate city-making, sustainable design perspective, it makes sense to get 60,000 people to a stadium via public transport systems, rather than clog up a gigantic area around the stadium with car-parking. It’s a mature way for people to move around,” says Brookfield. The site offers limited on-site car-parking, with no concessions even for event parking, a move that has been somewhat controversial. But that move, says Brookfield, created opportunities not often seen with these kinds of projects – the ability to fully integrate the stadium into extensive public open spaces and community facilities to accommodate a growing population. There is a new dedicated train station, bus hub, ferry terminal and pedestrian and cycling links, including the Matagarup Bridge, which allows pedestrians to cross the Swan River from East Perth and the CBD.

Optus Stadium Park. Image: Peter Bennetts

The Community Arbour links the stadium and park to public transport services. Image: Peter Bennetts

New train stations aim to encourage people away from their cars.

Works involved extensive landscape rehabilitation. Image: Robert Frith

Boardwalks along the Swan River provide renewed connections to the waterway. Image: Robert Frith

Newly established play spaces at Optus Stadium Park. Image: Peter Bennetts

Along with its progressive transport plan, the design team sought to carry out a process of “ecological and cultural healing”. They established key working relationships with the Whadjuk Working Group, Form public art consultants, and the Royal Life Saving Society among others in order to develop key ideas, with the ultimate goal of creating a new place that solidly connected with its location, history and community.

“The project offered a significant opportunity for us to push the brief forward in establishing a stadium park in Perth, Western Australia, on Whadjuk land” says Brookfield. While the stadium building – produced by the joint venture collaboration between Hassell, Cox and HKS, takes its architecture cues from Pilbara geology, the landscape precinct (lead by Hassell) provides a multi-layered interpretation of “WA-ness”.

Reduced car parking provisions enabled the team to explore the landscape’s potential, with its connections to the river and the lake, as well as the rehabilitation of the northern and western zones. The result is a nuanced design response, that balances tricky technical challenges, such as delivering a venue that can handle 60,000 capacity audiences, while also creating a public open space for every day community use.

A key feature in this regard is the 400-metre long Community Arbour and landscape corral system between the stadium and the train station.

“We wanted to establish an experience for people arriving and making their way to the stadium,” says Brookfield. Perhaps more importantly, this long approach mitigates a crush when people leave en-masse. Essentially it is a waiting system borne from extensive pedestrian modelling undertaken by Arup. “Twenty-eight thousand people will depart via train stations, when there’s a game on, and we didn’t want people to feel sheep penned.” Along with the arbour, which tells the Noongar creation story, the design features include bioswales, trees and strategic path diversions to help humanise the scale.

The Community Arbour tells the Noongar creation story. Image: Peter Bennetts

Design around the stadium building followed extensive pedestrian modelling. Image: Peter Bennetts

Small details are key to the parkland's appeal. Image: Robert Firth

Chevron parklands provides a sensory nature play experience. Image: Robert Frith

The fruits of the collaboration with the Whadjuk Working Party and Form are especially present in Chevron Parkland. The 2.6 hectare parkland is a nature play space thematically built around the six Noongar seasons: Djeran, Makuru, Djilba, Kambarang, Birak and Bunuru. Other elements that express this relationship can be found in the extensive use of public art, materiality and planting design.

The project had always been envisioned as a community place, open all-year-round, which meant finding ways to activate the precinct in as many ways as could be conceived, says Brookfield. “Sporting events and concerts take place up to 50 or 60 days of year, at the most. Many stadium precincts are dead when they’re not in event mode,” he says.

The stadium park is designed in three thematic bands running east – west across the site: the “landed” band to the east around the train station which acts as the gateway, the “parkland” band through the centre which includes the stadium and community ovals, and finally the “water side” band. The themes help create a varying and endlessly interesting range of experiences for visitors. “As a landscape architect, one of the top five things you’re always thinking about is the experience of people arriving and then moving through space. You’re always asking: what’s the amenity, what are the aesthetics and the environmental conditions that the design creates, effectively,” says Brookfield.

As he reflects on the project, Brookfield is particularly pleased with the finer layer of design detailing enabled by the project budget. “We’ve talked about a lot the big stuff, but when I go back down there now, I’m really happy with the micro level of design, particularly in the Chevron playground, like the little bronze turtles positioned on rocks. There was a lot of thought at that level, and it’s those details that we’ve managed to fashion through working with the artists, or through our own design and material selection across the site that offer all these surprising moments” he says.

Hassell’s achievements in Optus Stadium Park were recognised at AILA Western Australia’s Awards over the weekend, winning the overall WA Medal, excellence awards for Parks and Open Space and Play Spaces, and a Landscape Architecture Award for Urban Design.

See the galleries below for our coverage of all of WA’s winners for 2018.

AILA Western Australia Landscape Architecture Awards 2018:

The WA Medal and Excellence Award winners:

WA Medal: Optus Stadium park by Hassell. Image Peter Bennetts

Play spaces excellence award: Optus Stadium Park by Hassell. Image: Peter Bennetts

Parks & open space excellence award: Optus Stadium Park by Hassell. Image: Robert Frith

Civic landscape excellence award: Railway Square by Place Laboratory. Image: Dion Robeson

Cultural heritage excellence award: Railway Square by Place laboratory. Image: Dion Robeson

Community contribution excellence award: 'Place of Healing' plan by UDLA. Image: SKHAC

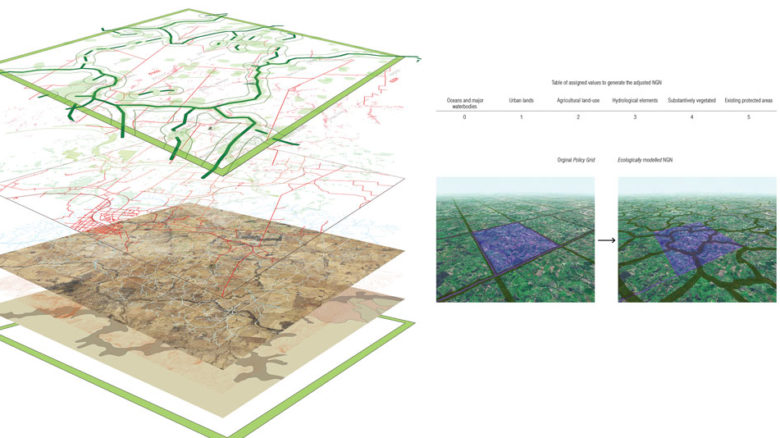

Landscape planning excellence award: Living Knowledge Stream design guide by Syrinx Environmental. Image: Syrinx

Excellence award for Research, policy & communication: Green Infrastructure plan by Simon Kilbane. Image: Simon Kilbane

People’s choice award and Landscape Architecture award winners:

People's Choice: Scarborough Beach Pool by Plan E

Infrastructure landscape award: Mills Park by Cardno. Image: Alana Blowfield

Civic landscape award: Newman Town Centre by UDLA. Image: Greg Hocking

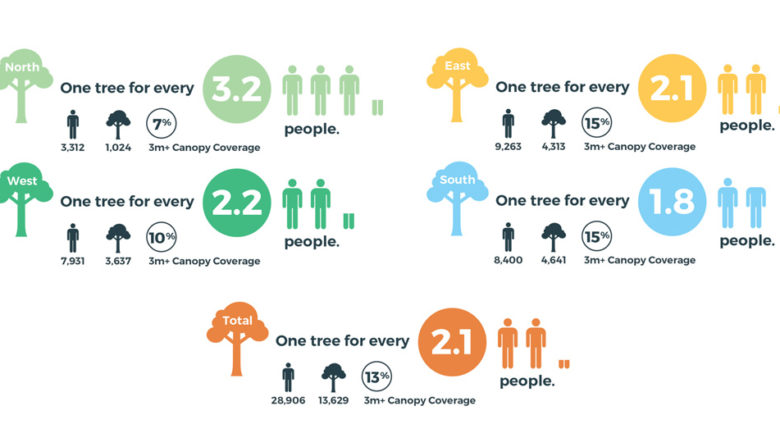

Planning landscape award: Urban Forest Plan by Ecoscape Australia. Image: Ecoscape

Play spaces landscape award: Rio Tinto Naturescape Kings Park by Plan E. Image: Jason Thomas

Urban design LA award: Optus Stadium Park by Hassell. Image: Hassell

View the full list of award-winning landscape architecture projects from this year’s Western Australia Landscape Architecture Awards above.