To make better streets, we must first measure them

The English mathematician and biostatistician Karl Pearson once said, “That which is measured improves. That which is measured and reported improves exponentially.” The question is, how do you measure a street?

The following conversation is an edited transcript from Foreground’s ‘The Street: design for people’ held at the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

Andrew Mackenzie: David, in your recent Foreground article you argue that we need to refit footpaths to meet current and future needs. This includes the co-location of pedestrians and robot delivery services. When it comes to the street there is a corresponding debate about when and if autonomous vehicles will ever be a thing. What are your thoughts – will we all be using AVs next year, in 50 years, or not at all?

David Levinson: Between next year and 50 years! My official timeline, and you can bank this, is that AVs will be available in the market in the United States and some other countries by 2020 or 2021. If you’re wealthy and you want to buy one, you will be able to. By 2030 autonomous mode will be standard on new cars. There might still be a steering wheel, but you will be able to push it into autonomous mode. And by 2040 human-driven vehicles would be prohibited.

AM: Presumably regulation for those AVs will need to keep up!

DL: Well, timing and sequencing will be critical, but frankly, until we get close to mostly autonomous vehicles, it doesn’t make a lot of sense changing how we use road space, because we still have to allow human drivers in between them. It then becomes a question of where it be fully autonomous first. Full autonomy will hit freeways, then campuses and parking lots, before it hits complicated environments such as the city streets. But remember, there are autonomous vehicles on the road right now in certain test sites around the US. It’s really a question of when, not if.

Once that happens we’ll see a lot of efficiencies. AVs can follow more closely behind each other, and function in a narrower lane. Most car lanes are currently 3.2 metres wide – much wider than cars, because humans are not very good drivers. Cars driven by robots will take up less space, allowing us to claw back a lot of street space for other uses. Parking spaces will also be smaller because AVs don’t need space for the door to open, so you’ll claw back space there too.

AM: The the reason I wanted to start this panel discussion with AVs, is because in different ways the question of regulation and standardisation was one underlying feature of each presentation today. Arguably automation, whether on the road or the pavement, carries some risks, not least because it represents a net increase in regulation. Yet informality, or the deregulation of the street, also has supporters.

Libby, when you were talking about your tree planting project in Blacktown, you mentioned that residents really took ownership of the project when they could make decisions about tree placement and species. This introduces a degree of informality, where the council has to trust that residents will make the right decisions. Given this dynamic of engagement could be seen as challenging to the strict codification of the street, do you think that this approach is scalable across the metropolitan region of Sydney?

Libby Gallagher: I do. I actually think that we’re addicted to standards. The research that I did really challenged my own preconceived ideas about setting standards. As soon as we started talking to the residents we quickly understood how this little nuance – placing a tree half a metre this way or that, in front of a door or offset from it – was a big deal for them. As far as standards go, it doesn’t matter too much if the trees are laid out on a 7-metre grid or 6-metre grid, as long as the trees are going in. Our desire to regulate everything is one of the biggest issues with street design. Within transport and traffic engineering there’s an attitude towards specialisation of road design that has been taken over by codes. This attitude shuts out opportunities.

My colleagues here that are landscape architects know how hard it is to get a slightly different approach to the street design, because we constantly come up against standards. Standards are often set in stone within councils and can be incredibly difficult to shift. When talking about different approaches to street design, whether we’re talking about trees or about safe spaces for women on the street, we need a nuanced response. One size does not fit all.

AM: Nicole, with your research into safety on the street, is there a correspondence between a person’s sense of feeling safe and the degree to which a place is regulated or not? You mentioned, for instance, that respondents felt safer in well-lit spaces, in places that had a police presence, and where there was less risk from ‘unpredictable’ people. Yet, as David mentioned in his presentation, cities are partly enriched by their unpredictability and serendipity. Can you talk about the correspondence between safety and control?

Nicole Kalms: It’s true that one of the things we love about city streets is that they’re unpredictable. People want to go into the city partly because unexpected things are going to happen. So it’s really a tricky thing to be doing the research we’re doing, and claiming that everyone has a right to feel safe all the time, when in fact part of the attraction of civic and street life, is actually the fact that you’re not. The work that we are doing, however, is about particular types of power relationships, including sexual harassment, that serve to keep women out of cities and out of public life.

If we really thought carefully about who is using the city, and how to divide all of the resources in a way that acknowledged women, of different ethnicities and abilities, we would intervene in cities in much different ways. There’s a place for regulation, in that sense. We need to pay attention to how we are ‘cutting up the pie”.

Nicole Kalms presents 'Free To Be', a crowd sourced research project on safety and gender

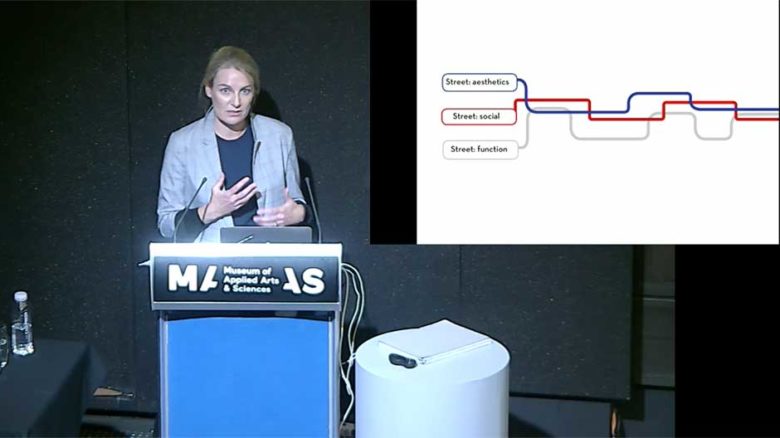

Libby Gallagher describes the social, aesthetic and functional role of the street

David Levinson explores the future of the footpath

David Levinson, Libby Gallagher and Nicole Kalms in conversation with Andrew Mackenzie

AM. Leading on from the question of how streets are controlled or regulated, we have seen in recent years a marked increase in community engagement, when it comes to planning decisions that will impact our streets and cities. Libby’s work is a good example. But this becomes much more challenging when dealing with billions of dollars, or major street infrastructure. David, are there opportunities to improve how people might participate in city-making at the large scale.

DL Definitely. My impression here in NSW, is that there is an amazing lack of transparency in decision-making, when it comes to major infrastructure. The government spends billions of dollars on a project, whether the project is good or not, and they don’t release the business case until after they’ve already made the decision. It’s considered cabinet-in-confidence, even though someone’s clearly going to either leak it, or the Freedom of Information Act will cause it to be revealed. Why wasn’t it revealed along the way?

That said, the advantage of this system is that Australia is actually building things now in a way that the United States can no longer do, because Americans have grid-locked themselves with public participation processes and legal challenges to infrastructure. I’ll give you an example from my first job out of college. I worked for the Montgomery County Planning Department, which was in a very high income suburb in Washington D.C. where a lot of government bureaucrats lived, and understood how government worked. There was a proposal to put a light rail line there, between two suburbs, on an existing freight line and right of way. They stopped running the freight in 1984 and in 1989 they said, “maybe you should make this into a light rail”. In the interim, they turned it into a trail, while the proposal was studied. They finally started construction in 2017, because it was tied up in the courts for 28 years, while the legal challenges ran their course.

I believe that there is a happy medium somewhere between no public participation in large billion dollar projects, and the grid-locking of project development. We should probably try to find out what that happy medium is. We are too far to one extreme of opacity here in New South Wales, and too far to the other extreme in the United States. The response to the freeway revolts in the 1960s, and the environmental impact regulations of the 1970s has greatly slowed down America’s ability to accomplish infrastructure there now.

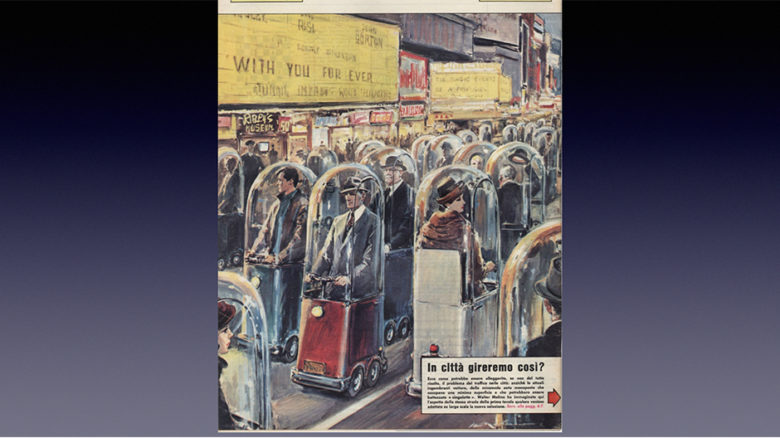

David Levinson considers early futuristic visions of the street

Libby Gallagher considers the street without cars

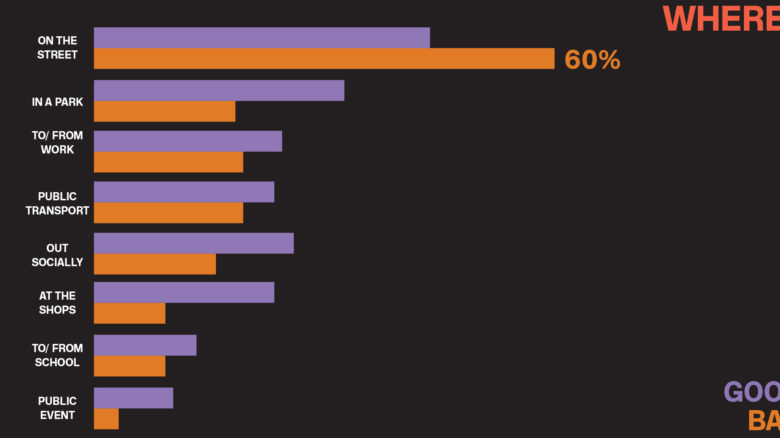

Nicole Kalms: the street is the place were good and bad experiences are heightened.

AM The work you have done Libby has won awards and been reported widely, and meanwhile there is some reason for optimism that NSW’s Green Grid draft policy will have an impact. Are you optimistic that there is actually a shift in the mood towards street design, and a better attitude towards tree canopy and dealing with the growing problem of the heat island effect?

LG Some days I am. Some days I am not. Obviously the fact that there is a strategic focus on the reasons for urban heat is good. I remember being told not to mention climate change when I was first undertaking public engagement. I was told that the counselors did not want to talk about climate change. All that is very much part of public consciousness now. We’ve hit a point when people are really feeling it, and really observing it in their own lives. Meanwhile everybody knows that when you stand under a tree on a hot day, it’s better. I do think though that it has to be an integrated approach, which means that what we value is really critical. We’re never going to get more trees if we’re constantly coming up against service providers who won’t allow them, because there’s some standard related to a garbage truck dimension, which disallows it.

Right now, we repeatedly have to have ludicrous arguments at the detail scale, which have the capacity to completely derail the big picture of having more green infrastructure. I very much welcome the Green Grid draft policy. I think it’s a fantastic initiative that could really improve the quality of our streets. But it has to filter down from big picture, to the obstacles at the detail level, to address that standardised approach.

We also have to put a dollar value on it. I have spent so many years trying to figure out the actual dollar value of trees. Nothing is valued until it is understood within an economic rationalist framework.

NK That is something we share, Libby. Part of our current research is trying to put an economic value on the cost of having women sexually harassed on the street. One of those economic costs is that those who are harassed often don’t want to use public transport spaces. So they may not use public transport for their whole entire life, as a result of being harassed on public transport spaces. When we understand that, we can then start to give it economic value, because that’s the only thing that politicians and policy makers care about.

You can play powerful videos, and have women and girls in the same room, describing their experiences, and they act like they want to do the right thing, but nothing cuts through better than economic cost.

LG There are also health implications, with the fact that women and young girls are not walking as much as they might, because they’re terrified to walk. That’s a huge economic cost across society

AM Nicole, your presentation has clearly detailed a problem with gender and safety on the street. You mentioned that the full report associated with the Free to Be research project will be coming out in October. Without preempting the outcomes of that report, are there specific policy recommendations that you can point to, as a result of the project? What next?

NK One positive policy change would be the removal of all sexualised advertising in public spaces. It happened some time ago in France and in parts of northern Europe. That’s just got to happen too. But so far we’re incredibly lax about that.

I’m really advocating for bringing back clear gendered strategies in public policy documents, and that’s what we’re going to be working on with the XYX Lab and following up with our stakeholders.

As a final anecdote, there’s one transport provider in Sydney that has made comment about LGBTQ people traveling on public transport, saying that they should “cover up” when they go out, so that they don’t get beaten up. That’s the only gendered language we can find within public transport advice to citizens. That has to change.