More bike paths like these, please

Two recent award-winning projects demonstrate the vital importance of bike paths and other active transport networks within our urban infrastructure matrix.

On the morning of 25th March 2018 a motley crowd of locals, cyclists and campaigners gathered to witness the opening of Darebin Yarra Trail Link, which would finally provide a vital link to more than 600 kilometers of metropolitan off-road trails. For some attending, it was the end of a long torturous journey that started a quarter of a century before. Perhaps that’s why the Bicycle Network described this relatively modest project as, “surely equivalent to Caesar’s fateful crossing of the Rubicon”.

When considered next to a planned 2018-19 $2.2 billion investment in Victorian suburban road upgrades, the Darebin Yarra Trail Link’s $18 million budget is certainly a minnow for VicRoads, whose urban designers and structural engineers undertook the project. Yet the opening of this cluster of bridges and pathways could well be seen as an iconic moment, and a victory for all those who believe that active transport plays a vital role in any city’s infrastructure mix. Despite delays from Boroondara Council, lapsed planning permits, resistance from LaTrobe Golf Club and concerns from some locals, the project opened to fanfare and jubilation.

As one of this year’s winners in the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects Victorian awards, the Darebin Yarra Trail Link is also notable as a project wholly undertaken by VicRoads – that is to say, within the public sector. As a project that includes several land purchases, an important slice of urban forest, local government tensions and some very seasoned and vocal campaigners, it is perhaps not surprising that the project’s design was undertaken ‘in-house’.

For VicRoads Principal Urban Designer and landscape architect, Ann Morgan-Payler, the recent award the project won is not taken lightly. “I think it’s quite important for a government department like VicRoads to have design teams that can take on a project like this and win awards,” says Morgan-Payler. “Many government departments right across Australia have lost design capability. They’ve just become design reviewers. But VicRoads still has an ability to do this sort of stuff.”

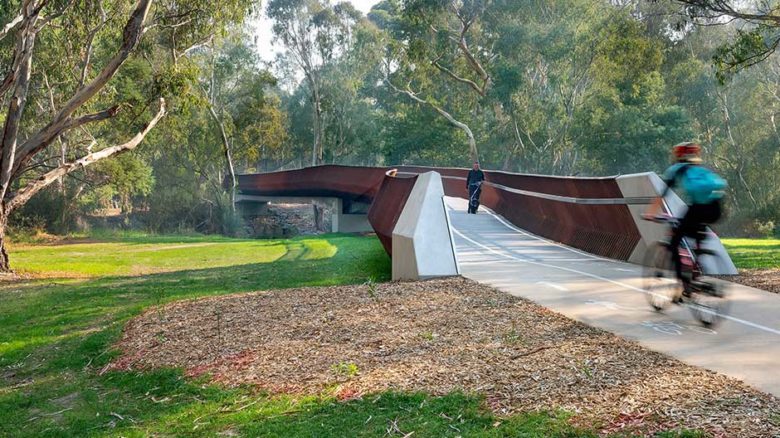

The fact that the project team included designers and engineers working closely together under the one roof perhaps assisted in balancing structural requirements and design aesthetics, particularly in the delivery of the four bridge portions of the project. This resulted in a reduced depth in the bridges’ superstructure, which in turn delivered sinuous curvaceous structures that integrate sensitively into the bush setting. In place of utilitarian steelwork and default materials, the project brings together raw rusted steel, a naturalistic colour palate, unsealed timber and concrete, in a form that celebrates the relationship between users and the natural environment.

Darebin Yarra Trail Link by VicRoads Urban Design Team and VicRoads Structural Design Team. Image: Emma Cross

Darebin Yarra Trail Link by VicRoads Urban Design Team and VicRoads Structural Design Team. Image by Emma Cross

Darebin Yarra Trail is 1.8 kilometres of bike paths linking Melbourne's North-East. Image: Emma Cross

Taken as a whole, its relatively modest scale is nevertheless a significant achievement for VicRoads, Morgan-Payler and her multi-disciplinary team of urban designers, landscape architects and horticulturists. She is also quick to point out the important role played by the VicRoads team of 12 structural engineers.

“As protectors of the public realm, we have the opportunity to be strategic about how individual projects connect to wider plans. This capacity within the public sector needs to be protected” says Morgan-Payler. “If we don’t have the capacity within departments to be properly involved, we risk ending up with a patchwork quilt of every consultant’s or stakeholder’s view of a particular project, and that’s not always strategic.”

Another award winning project that celebrates pedestrian and bike path connectivity is located in the fast growing west Melbourne suburb of Truganina. Here, Skeleton Creek bisects a neat grid of sub-divided blocks, as it winds its way south to the bay. When the landscape architecture practice Site Office was initially commissioned to design a small park on the eastern bank of the creek in 2012, much of the surrounding landscape was little more than bare dirt, awaiting services. By the time housing construction started, it quickly became clear that a bridge was also needed, to connect communities across the creek.

Site Office began discussions with council, to explore what that bridge could be. “Initially council had a strong preference for an off-the-shelf bridge” says Site Office director Christopher Sawyer, “but we encouraged them to think about the value of a piece of infrastructure that fitted, in a more integrated manner, onto that site.” Eventually council agreed, and asked Site Office to explore designs for a bridge that could be competitively priced, yet also respond sensitively to Skeleton Creek.

Site Office designed two elegant bridges to cross Skeleton Creek in Truganina in Melbourne's West. Image by Lisbeth Grosmann.

The Skeleton Creek Bridges are lightweight steel framed bridges with minimal impact on the creek's capacity. Image by Lisbeth Grosmann.

Skeleton Creek Bridges by Site Office, winner of the 2018 Landscape Architecture Award. Image by Lisebeth Grosmann

“A lot of our design intent in this project, was to avoid the visual bulk of bridge infrastructure,” says Sawyer. “With off-the-shelf bridges, the structure is completely exposed, and it’s not particularly pretty. So we worked closely with ARUP to figure out how we could streamline the structure, effectively disguising it, in the cladding of the bridge.”

As with Darebin Yarra Trail Link, the success of Skeleton Creek is the result of close collaboration between design and engineering. What marks this project out as unusual, in the context of bridge delivery, is the fact that it was led by landscape architects, with the engineers as sub-consultants to the project. This fact is not inconsequential in its success.

As Sawyer notes, “there is no doubt that landscape architects tend to take a substantially different approach to a project such as this. Architects and engineers often focus on the structural solution that underpins the bridge, and the result can be overly articulated and heroic. We weren’t interested in this approach. We begin from the reverse position – how to minimise the bridge’s visual and physical impact on a fragile creek.”

While the water quality of the creek is poor, due to polluted run-off from surrounding roads and high nutrient loads in run-off from nearby market gardens, the creek remains an important biodiversity habitat. Like many urban waterways Skeleton Creek is a resilient ecological feature, providing linkages for natural systems and life cycles. So this project is not just about connecting suburban communities, it is also about improving the creek as a habitat and biodiversity corridor.

Two projects, each small in scale, yet significant in impact. Taken together they demonstrate that bike and pedestrian paths should no longer be considered the poor cousin to roads. Cheap, they may be, but thanks to their lighter loads and leaner structure they have the capacity to embrace light-footed design that allows their integration into even the most fragile natural ecosystem. They are a healthy, low energy, low cost alternative means of getting around the city, and we need more of them.

AILA Victoria Landscape Architecture Awards 2018:

Cultural heritage award of excellence: Point Nepean National Park Master Plan by Taylor Cullity Lethlean and Parks Victoria.

Tourism landscape architecture award: Falls to Hotham Alpine Crossing Master Plan by McGregor Coxall.

Play spaces landscape architecture award: Mirambeena Park, Warralily, Armstrong Creek by GbLA.

Parks and open space award of excellence: Alpine Better Places, Porepunkah by MDG Landscape Architects.

Gardens landscape architecture award: Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre by Rush Wright Associates.

Research policy and communications landscape architecture award: Monash University - Civil Engineering Hydraulics 'Living Lab' by Aspect Studios.

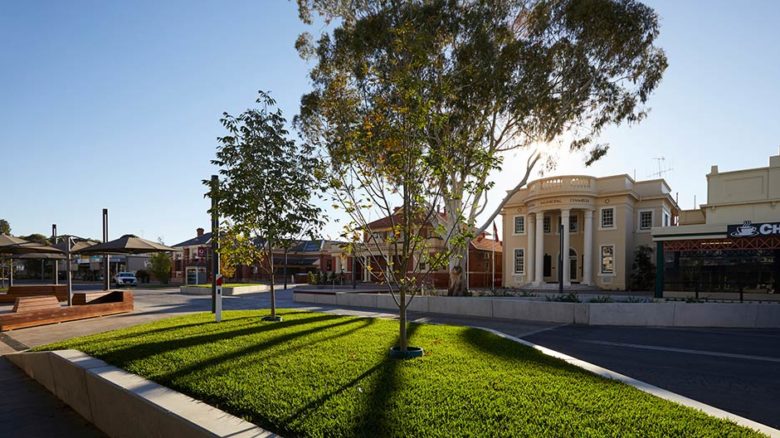

Urban design award of excellence: Victoria Square, Kerang by Hansen Partnership.

Tourism award of excellence: Parks and open spaces landscape architecture award: Williams Reserve, Richmond by Hansen Partnership by Urban Initiatives.

Parks and open spaces landscape architecture award: Williams Reserve, Richmond by Hansen Partnership.

Play spaces landscape architecture award: Booran Reserve Playspace by ACLA Consultants.

Community contribution landscape architecture award: Livvi's Place Craigieburn by Aspect Studios.

Gardens award of excellence: Earth Sciences Garden, Monash University by Rush Wright Associates.

Small projects award of excellence: Immigration Museum Activation Project by Rush Wright Associates.

Land management landscape architecture award: The System Garden Masterplan by Glas Landscape Architects.

Small projects landscape architecture award: Valley Lake Lookout by McGregor Coxall.

Play Spaces landscape architecture award: Ballam Bumps Regional Playspace by Playce.

Urban design landscape architecture award: Geelong Laneways Precinct by Outlines Landscape Architecture.

Civic landscape, landscape architecture award: Dawson Street Precinct Sunshine by Fitzgerald Frisby Landscape Architecture.

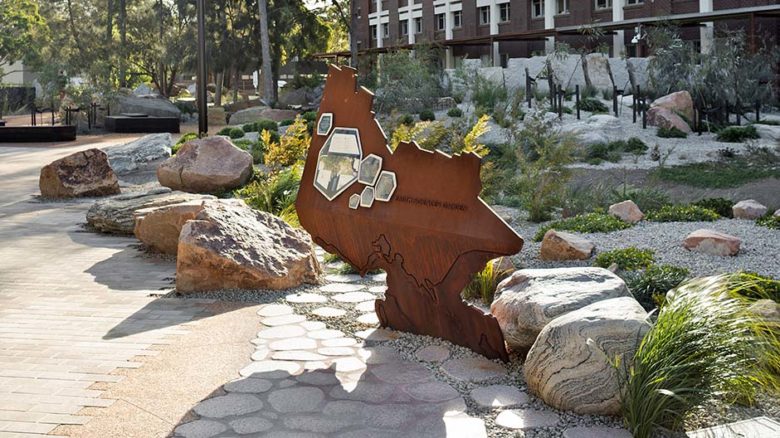

Civic landscape, landscape architecture award: MADA West Courtyard by Glas Landscape Architects.

Small projects landscape architecture award: Tarrawarra Abbey by Aspect Studios.

Gardens landscape architecture award: MPavilion 2017 by Tract Consultants.

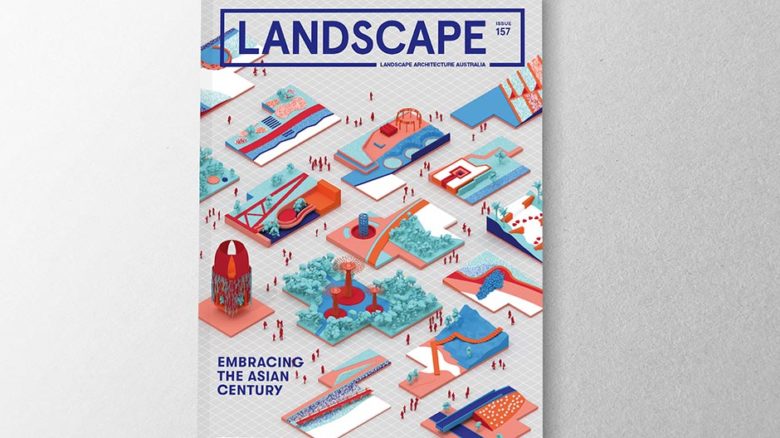

Research policy and communications landscape architecture award: 'Embracing the Asian Century', Landscape Architecture Australia by Jillian Walliss, Heike Rahmann, Ricky Ray Ricardo.