When it comes to urban infrastructure, big doesn’t have to mean bad

Provision of well-engineered transport, energy and other service infrastructure is essential to good urban functionality. But as Australia undergoes an infrastructure boom, let’s not forget these major works can and should contribute to the social, cultural and human qualities of our cities.

Urban infrastructure can range in scale, from the metropolitan to the human, from highways to bus-stops, dams to drinking fountains. These elements provide the overarching organisational structure that ensures our cities run smoothly.

Discussion of urban infrastructure often revolves around two categories – ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure. ‘Hard infrastructure’ refers to the physical networks that are required to service large metropolitan areas, including sewerage, energy, transport, waste management and telecommunications systems. ‘Soft infrastructure’ refers to the less tangible networks of places, policies or strategies that are designed to support the economic, health, cultural and social needs of cities.

Too often, a purely hard approach results in urban infrastructure that fails to address the social and human dimensions of living in an urban environment. From the regulation-standard fire hydrants that litter our urban streetscape, to the anti-terrorism concrete bollards that fortify our public space, the design of urban infrastructure can often detract from the ideal urban experience.

Multi-functional urban infrastructure

Well-designed infrastructure networks overlap. For instance, in planned cities, systems of hard infrastructure are often designed to share a defined spatial zone. Road easements act as conduits for vehicular and foot traffic, electricity poles delineate a zone overhead, while subterranean infrastructure, such as fibre-optic cabling, sewerage, and other piped services run below. The urban renewal of innovation district 22@ Barcelona involved the implementation of shared infrastructure space for sewerage, pneumatic waste collection, precinct-based climate control systems and subterranean fibre-optic cabling.

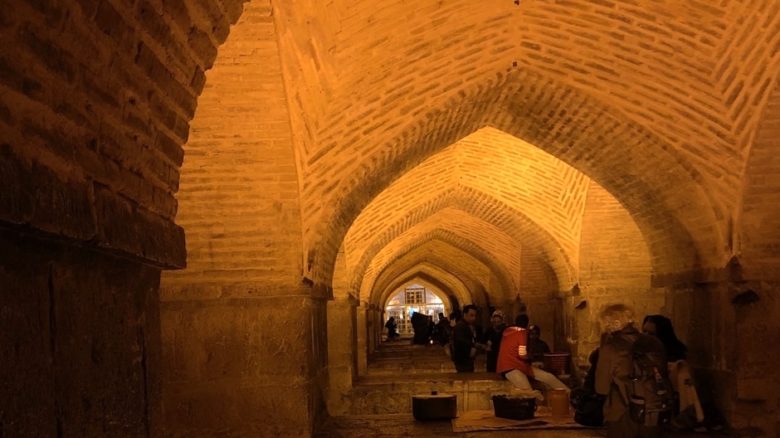

Historically, there has always been a blurring of soft and hard infrastructure. For instance, the daily ritual of communal bathing in Ancient Rome cohesively combined soft and hard infrastructure through the pairing of social activity with necessary hygiene facilities. This relationship between social and physical service infrastructure spans countries, cultures and eras. The city of Isfahan in Iran, the capital of the Safavid Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries, has become known for its impressive Perso-Islamic architecture, notably its mosques, boulevards and bridges. Its network of bridges, implemented and built during the Safavid era, still operate as vital urban transport infrastructure that helps stitch the city together across the Zayanderud River. However, it is their unique coupling as a social infrastructure that has allowed them to become popular urban meeting places. Khaju Bridge operates primarily as a bridge enabling pedestrian connectivity, but it is also a weir, a building and a much-loved public space where people gather and sing under its vaulted arches.

Trees and other urban vegetation may offer the ultimate mix of services as green infrastructure. They provide a range of ecosystem services, cleaning air, reducing city temperatures and the urban heat island (UHI) effect as well as making delightful and welcome places to congregate and recreate. The vegetation species of social spaces such as local parks, streetscapes and plazas can also provide much-loved elements that lend specific character to public places, reflecting local culture and history.

Footscray's traders and locals repurpose the streets' transport and utility infrastructures. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Every Friday, a multi-storey car park in Tehran transforms into the bustling Jomeh Bazaar market. The market hosts stall owners from all across the country and Central Asia. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Isfahan’s Khaju Bridge serves multiple uses as transport infrastructure and vital social infrastructure. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Isfahan’s impressive array of architecture earned it the saying ‘Esfahan is half the world’. Khaju Bridge has become famous as a meeting place for young groups of men to sing in public. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Learning from informal urbanism

In the western world, the reliability, familiarity and formality of our urban infrastructure enables it to recede into the background of our urban environment. Railway tracks and power poles become generic urban elements that are taken for granted, viewed as essential yet unchangeable requirements for the operation of our cities. Robin Boyd’s The Australian Ugliness drew attention to the visual dominance of the infrastructure littering Australian cities from the 1950s, especially the then-new television aerials. These elements found their way onto the covers of various editions of the book and included electricity poles, overhead sewer methane vents and litter bins.

Informal urbanism offers a different perspective of the ways that urban infrastructure can be designed. In informal settlements, elements of urban infrastructure are seen as opportunities to appropriate, generate and order space through individual or collective agency. Existing elements can be adapted and re-purposed with a new meaning, allowing them to serve more than one purpose. A bridge doubles as a social meeting place, a highway becomes a well-traversed commercial strip or a lamp-post becomes a spatial and structural element to display wares for sale. Through this type of appropriation and adaptation, urban infrastructure is able to generate social and cultural value.

This appropriation of urban infrastructure for multiple and local purposes, is already happening in Melbourne, albeit largely under the radar. In Footscray, examples of everyday urbanism and adaptations of infrastructure are prevalent across the suburb. A bus-stop doubles as an extension of a grocer and a footpath becomes a place to sell culturally unique commercial wares. These appropriations of our urban infrastructure help give our cities and neighbourhoods their unique personalities.

Re-thinking transport infrastructure

Globally, transport infrastructure is perhaps the most recognisable and dominant form of urban infrastructure. Road networks, whose major purpose is to service the needs of private vehicles, are the most prolific and visible element. In Australia, a large portion of the federal budget for infrastructure is dedicated to road spending. In Melbourne, despite the evidence of the multiple problems caused by supporting car-dependent cities, and the rejection of the proposal by Victorian voters, the federal government has promised funding for the East-West Link tollway. Even at a local scale, council car parking requirements have enabled vehicular-related infrastructure to overflow and dominate our public spaces. Car-infrastructure often only serves one purpose. Is there an opportunity to inject social or cultural meaning into its otherwise generic urban element?

In Tehran, a multi-storey car park operates as a car park from Sunday to Thursday. But every Friday, it transforms into the bustling Friday market of the Jomeh Bazaar. The scale of car-spaces offer an ordering system that allows for market ‘stalls’ to be demarcated in a temporary manner. An under-utilised urban car park totally transforms into a weekend destination for urban residents, offering an alternative version of public space.

In Victoria, the recent Level Crossing Removal Program (LXRP) has helped to realise the potential of pairing large-scale infrastructure renewal with new forms of public space. The aim of the program is clear; to separate vehicular traffic from railway corridors as a way of decreasing road congestion and simultaneously improving train services. In Melbourne’s suburban context, elevated rail presents many further benefits. Primarily, the removal of what was formerly divisive infrastructure for pedestrians, creates an opportunity for designers to bring people together. Elevated rail provides opportunities for both improving strategic transport and creating new public open spaces. This is particularly valuable in locations where there is little space for neighbourhood amenity. This integrated approach to urban design demonstrates the potential that large infrastructural projects have when engineering requirements are paired with contextual and human-centred design thinking.

The Pasupati overpass in Bandung, Indonesia attracts a wide range of street vendors, activating an otherwise dead space beneath. It holds social and cultural value for surrounding residents. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Table Tennis provided as part of new public plaza spaces by ASpect Studios beneath elevated rail. Photo: Peter Bennetts Photography

The Melbourne Art Tram project is also a great example. A major public art project has used transport infrastructure as a way to imbed cultural value in a mobile urban context. The project is a continuation of the Transporting Art project, which ran from the late 1970’s to the early nineties. While the project has created a new platform for Melbourne’s art community, unfortunately it has been used as a precedent for the commercialisation of public infrastructure through advertisements.

The design of our transport infrastructure can be improved at a finer-grain scale. The city of Utrecht in the Netherlands has recently transformed over 300 bus stops into a network of bee sanctuaries. This has been completed through simply converting the roofs of the city’s bus stops into a grassy surface with wildflowers in order to encourage pollination. This adaptation of existing infrastructure has been an effective way of improving urban air quality and encouraging biodiversity.

Cultural values

Well-designed, human-scaled infrastructure can hold deep social and heritage value for a city. We would find it hard to imagine Tokyo without its distinctive pedestrian crossings or Paris without its iconic Art-Nouveau metro stations. Urban infrastructure can be used as an effective place-making tool, able to emit its own unique and distinctive ‘urban’ personality.

The recent announcement of the removal of Melbourne’s city newsstands is an example of planners and policymakers failing to recognise the social value of fine-grain urbanism, even when the original purpose of the urban element has been superseded. The council has declared that they create ‘bottlenecks’ for foot traffic and that their functions have become ‘anachronistic’. While newspapers might not be sold as much today, these newsstands have become a recognisable element of Melbourne’s urban environment. They are easily adaptable to host alternative commercial activities and activate urban streetscapes.

Appropriating urban infrastructure

In some cases, the design of urban infrastructure elements can be used – and reused – to advance political agendas. In Melbourne, the overnight appearance of anti-terrorism traffic bollards throughout the city in 2017 was a response to a series of violent local and international events, reinforced by a devastating vehicular attack in Bourke Street in November 2018. Over 100 concrete-bollards were strategically located near major train station entries and along Bourke Street. While the design of a defensive urban infrastructure might be an effective short-term policy in preventing urban terrorism, these concrete-bollards set a dangerous precedent for the way we think about the design of public spaces.

The restrictions of hostile architecture should be considered a direct threat to the open, vibrant and human qualities of public space Melbourne is renowned for. Despite this, their appropriation and adaptation by Melbourne’s artistic and cultural communities have demonstrated the powerful influence that citizens can have in reclaiming public space and recycling urban infrastructure. In Melbourne, architects and designers have also begun responding to this narrative of public space. Openwork’s design of an “alternative to the concrete bollard impact barrier”, draws attention to the human qualities of infrastructure.

There are many ways that permanent urban infrastructure can be appropriated and localised. Urban Smart Projects is an urban street art initiative which gives local artists opportunities to paint traffic signal boxes across the country. The scheme seeks support from local councils and creates a framework whereby local artists are given a platform to display their work. Other precedents for using art as a method of beautifying and localising urban infrastructure include the painting of Adelaide’s ‘stobie poles’ which is supported by local councils.

An example of visual integration of service cabinets with structure facade in the urban public realm. Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Award-winning City of Melbourne newstands were part of the suite of urban infrastructure designed by Ian Dryden for the city's streets. Photo: Jimi Connor

The phenomenon of poorly integrated service cabinets have demonstrated the destructive potential urban infrastructure can have on the public realm Photo: Tahj Rosmarin

Recognising the human qualities of our cities

Of course, not all elements of urban infrastructure are easily adaptable. But that does not mean they should ignore the human-scale, or local values. The proliferation of badly integrated service cupboards for hydrant and sprinkler boosters in Melbourne are a perfect example of how infrastructure can be damaging to the built environment if it fails to address the human scale. Service cabinets are a necessity in meeting building code regulations where street accessibility and functionality are priorities. But can these elements be designed in a way that is not damaging, and might even contribute to the experience of delight in our urban environments?

The City of Melbourne’s Central Melbourne Design Guide offers examples and is an important tool in improving the quality of development outcomes, including impacts on the human experience of the street. It is a great step towards improved human-scaled infrastructure design, specifically highlighting the need to improve the design outcomes of service cabinets in central Melbourne.

It is common knowledge that Australia is undergoing an infrastructure boom. While state governments are vying for a piece of the multi-billion dollar funding pie, it is imperative that the discussion includes a consideration of design quality and public benefit.

How will our new infrastructure recognise, value and contribute to the social, cultural and human qualities of our cities?

–

Tahj Rosmarin is a Melbourne-based urban designer and architectural graduate of the University of Melbourne. His research is focused on changing urban conditions, “multi-cultural urbanism” and bottom up, participatory based architecture.