The flood: Designing cities for deluge

With the 10-year anniversary of the 2011 Brisbane floods approaching, Amalie Wright takes stock of what the city has learnt about the challenge of living with increasingly unpredictable and extreme levels of rainfall.

By the middle of January 2011, after nearly a decade of drought, Queensland was inundated with a record-breaking wet period of prolonged intense rain. The subsequent flooding affected nearly 80 percent of the state, claiming the lives of 33 people, and damaging or destroying 29,000 homes and businesses at a cost of more than $5 billion.

Nearly 10 years on, south-east Queensland dam operators still face intense ongoing scrutiny and a multimillion-dollar payout after a class-action lawsuit found four engineers failed to release enough water before ‘biblical’ rainfall, exacerbating downstream flooding.

Not far from the dam, one flood-affected town has voluntarily relocated to higher ground.

Legislative changes mean that the responsibility for identifying and mapping flood risk lies with local councils, which are now more risk-averse when assessing new developments in flood prone locations. At the same time, existing residents have been unhappy with redrawn flood maps that now show their homes ‘at-risk’, and with potentially decreased property value.

Across the state buildings and infrastructure have been rebuilt or constructed at higher levels, and in ways that make them more likely to survive future inundation. Emergency response coordination has been tightened.

The ways in which Queensland responded to the 2011 disaster reflect the four main ways people have historically responded to floods: by either trying to hold them back, retreating from their path, minimising their impact, or understanding, accepting, and planning for floods to recur.

But while these responses may be universal, the ways in which they are combined, and the emphasis placed on one over another are specific, influenced by our societal norms and our understanding of the places we inhabit.

A flooded Milton Road, in the heart of Brisbane, during the 2011 floods. Image: Erik Veland

South Brisbane's South Bank and Brisbane Eye inundated after the 2011 floods. Image: Allan Henderson

Flood-damaged household items removed from Brisbane homes after the clean-up. Image: Edeink

Landscape architect Alvin Kirby gained an accelerated education in living in the Brisbane River floodplain. He’d moved from Tasmania to the inner-city suburb of West End with his teenage daughter in October 2010 and was waiting for the rest of the family to arrive. He’d experienced the wet summer in Brisbane, including the nearly 500mm of rain that fell in December 2010, three times the recorded average for the month.

On 10 January, Toowoomba was deluged by fast-rising flash flooding after 90mm of rain fell over the city in an hour. In what the Queensland Police Commissioner would later describe as an “inland tsunami”, the flood surge moved rapidly downstream into the Lockyer Valley, washing away livestock, structures, and people as it swept through the towns of Murphy’s Creek and Grantham.

Kirby was at work two days later when warnings started coming through that river levels were rising. The English-born Kirby recalled that “I’d never had an experience of flood in my life”, but following the press coverage of events in Toowoomba and Grantham he now had a “strong image of these huge torrents of water rushing through”.

Intense rainfall had dropped an additional 700mm of water over the already saturated Brisbane River catchment. Water from the Bremer River and Lockyer Creek flowed into the Brisbane River and headed towards the capital city.

Kirby called his daughter, “somehow” made it home, grabbed essentials, phoned his wife in Tasmania and then “we jumped in the car and drove to the top of Dornoch Terrace [a local high point] and assessed what the next move could be.” They spent the night safely with friends. The following day the rains cleared and the sun came out, but by the time Kirby arrived home floodwaters had already entered the lower level of his house and destroyed possessions.

Malcolm Snow also remembers the change in weather. At the start of 2011, he was entering the final year of his tenure as CEO of South Bank Corporation, the statutory authority responsible for the planning, development and management of the popular riverfront precinct, extending across a 17-hectare location opposite the Brisbane CBD. On the morning of 13 January the river spilled into the parklands, the lagoon pool, tenancies, and underground carpark. Snow recalls standing at his office that morning, seeing “sunny weather, yet South Bank was flooding before our eyes.”

The waters were still receding when the clean-up began. Much of the clean-up was done by community volunteers, the 50,000-plus members of the ‘Mud Army’, named for the silty muck left behind alongside tonnes of waterlogged items. Alvin Kirby recalled the “stench of mud and river debris” increasing with the continued sunshine, until “it hung in the air for days”.

After the clean-up came the questions.

The aftermath of flooding in Toowoomba, 2011. Image: Timothy Swinson

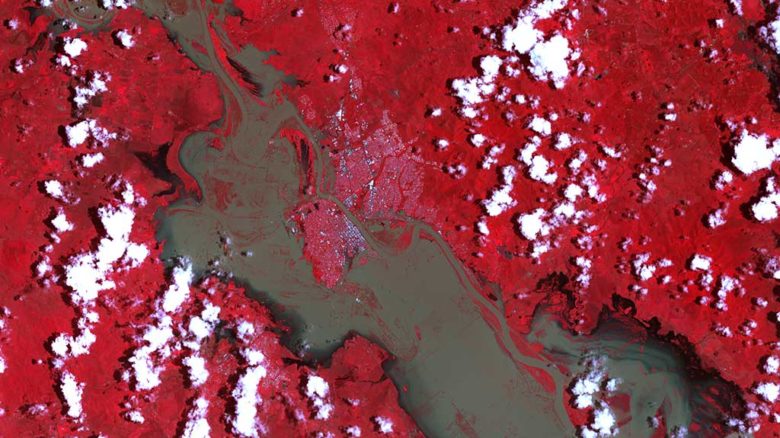

Infra-red satellite image show the town of Rockhampton (white flecks in the middle) surrounded by the swollen Fitzroy River. Image: NASA Observatory, January 2011

Remains of a flood damaged utility truck in Grantham 2011. Image: Angela Ritchie

Within tightly defined terms of reference, the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry spent 14 months hearing expert submissions, conducting public hearings across the state, and developing 177 recommendations, 40 percent of which concern floodplain management, planning, development, and building codes.

State and local governments bear different responsibilities for flood risk management. The Queensland Government sets the strategic intent: for floods it requires that “the risks associated with natural hazards, including the projected impacts of climate change, are avoided or mitigated to protect people and property and enhance the community’s resilience to natural hazards.”

Local councils have primary responsibility for completing and maintaining up-to-date flood studies and information and incorporating the results into planning schemes.

So what has this meant in practice? Alan Hoban, President of Stormwater Australia and Queensland ‘Engineer of the Year’, 2020, has observed “greater conservatism”, with local governments “less likely to compromise” on development in flood prone areas.

Hoban has observed the challenges faced by some councils when grappling with the implications of state requirements, current flood studies and existing local planning zones. Queensland’s 2016 Planning Act retains a compensation provision which enables owners of property affected by an “adverse planning change” to claim compensation from the relevant council. At face value, a land use zone or line on a map may reflect the findings of flood modelling, but when that translates into “economic winners and losers” it can make for difficult conversations with affected communities.

Moreton Bay Regional Council, to the north of Brisbane, received backlash from residents when it released updated flood maps with its Draft Planning Scheme in 2014. Owners, backed by the real estate industry, claimed that property with no flood risk previously attached to it, or no known history of flooding, would now lose value, not be useable for some types of development, and attract higher insurance premiums. Then Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development, Infrastructure and Planning, Jeff Seeney, refused to sign off on either the plan scheme or flood maps until community concerns had been “adequately addressed” by council.

In Grantham, one experience of catastrophic flooding was enough to convince the community to relocate. Having survived flood waters moving at two to three metres per second, rooftop helicopter rescue, and loss of friends and family, Grantham residents were supported by then-mayor Steve Jones, who quickly rallied support for clean-up. Working with Jones in the days immediately after the flood was Jamie Simmonds, who stayed on to manage the project to relocate and rebuild the town. The experience was addressed in the Flood Inquiry, and detailed by Simmonds in his book Rising from the Flood: Moving the Town of Grantham.

A suitable parcel of land—elevated, large, close, unconstrained— was available for purchase by the Lockyer Valley Regional Council. Having done so, Council could implement a voluntary land swap arrangement allowing “eligible property owners … to ‘swap’ their land for part of the newly purchased council land.”

The design of a new 120-lot estate was informed by extensive community consultation and then formalised. The first relocated residents moved into their new homes less than a year later, and subsequent council data shows the population has actually increased from pre-flood numbers.

Several factors contributed to the pace of implementation. As well as the land being available, Council was financially positioned to effect the purchase. The decision to rebuild was made quickly and the town declared a reconstruction area, giving the Queensland Reconstruction Authority (QRA) coordination responsibility, and enabling a number of typical approvals processes to be waived. It could also be argued that having a relatively small, homogenous population with a shared experience of the flood, made for a more straightforward process of consultation and negotiation.

While participating Grantham residents received their new blocks of land free of charge, they were responsible for financing their new homes, which most did through insurance payouts. Working with insurance providers and property owners throughout south-east Queensland in the aftermath of the floods has enabled architect James Davidson to become a specialist in flood-resilient building design.

In 2011, Davidson was director of Emergency Architects Australia (EAA) and in the months following the flood he coordinated a team of over 120 volunteer architects, engineers and students that spoke with 1200 families at public gatherings and conducted pro-bono inspections of over 230 flood-affected homes.

The program deliberately focused on suburbs where fewer people were insured or had ready access to information on rebuilding safely. Assessment checklists helped individual homeowners regroup and provided a valuable insight into the ways different types of houses had responded to inundation.

After the immediate crisis Davidson continued to work with individual homeowners, informed by lessons learned from the EEA program. Assessments revealed that some commonly used contemporary construction methods hindered recovery. When plasterboard-clad walls were inundated, for example, they trapped silt and mud inside the timber frame, requiring demolition of the entire wall, while raised door sills prevented water escaping and hindered clean-up. Building on this knowledge, Davidson worked with the Queensland Reconstruction Authority to develop its Flood Resilient Housing Guidance for Queensland Homes.

Most recently Davidson has been working with Brisbane City Council to help deliver its Flood Resilient Homes initiative. This is being trialed in locations with a history of frequent, severe flooding from overland flow, and 890 homes will be retrofitted during the pilot program. Works carried out have included raising washing machines and dryers, installing different electrical circuits on different house levels, and replacing non water-resistant cabinetry and flooring with water-resistant alternatives.

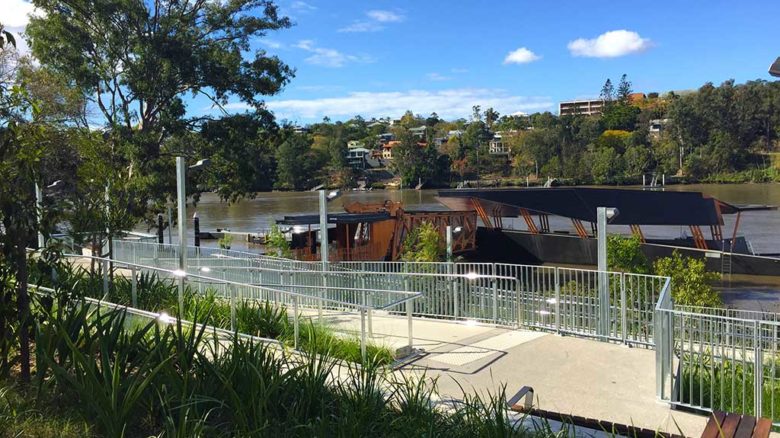

In addition to the Flood Resilient Housing Guidance, Queensland Government Architect Malcolm Middleton also points to the work done to repair ferry terminals along the Brisbane River as a significant architectural and landscape response to the floods.

The Flood Inquiry briefly addressed Brisbane’s ‘river architecture’: the New Farm Riverwalk, ferry terminals, and private pontoons. Seven of the city’s 24 ferry terminals suffered extensive damage requiring major repair or replacement. A Queensland Government design competition aimed to find a solution with greater flood resilience, as well as improving accessibility, network efficiency and connection with the river.

The winning scheme, designed by Cox Architecture and Aurecon, with landscape architecture by Lat27, included three solutions: shaping the pontoons to deflect river debris; designing hinged gangways to float and swivel with the force of floodwater; and providing a single pier robust enough to withstand vessel impacts and prevent pontoons floating away. Delivery of these seven terminals was completed in 2015. Council has continued to upgrade an additional 10 terminals, although work appears to have focused primarily on ensuring equitable access, and the design of the first seven terminals has not been reproduced.

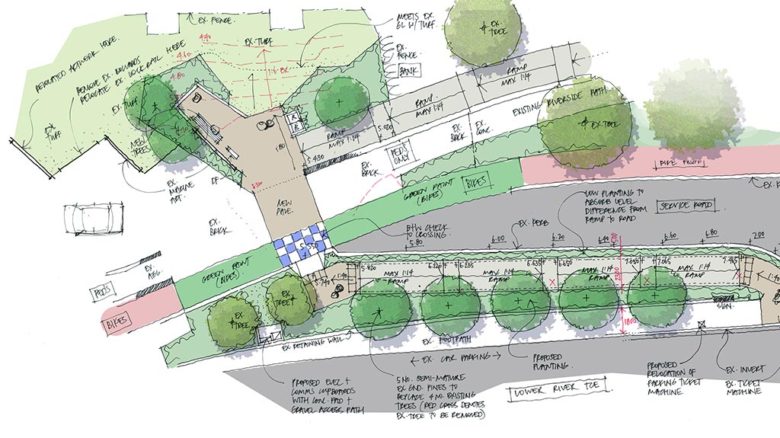

Each design for the individual terminals improved accessibility for passengers including adding formal pathways and bike lanes. Image: Lat27

Brisbane Maritime Museum Ferry terminal 1. Image: Lat27

Lat27, in conjunction with Cox Architecture and Aurecon, provided 8 ferry terminals along the Brisbane River. Image: Lat27

The new ferry terminals needed to accommodate both flood events and the river's tidal range of 2m. Image: Lat27

Damage to Brisbane’s river architecture was caused by the volume and velocity of floodwaters, which included water released into the river from upstream Wivenhoe Dam, a dual-purpose water storage and flood detention facility. Arguably the most publicly scrutinised recommendations of the Flood Inquiry were those concerned with the operation of Somerset and Wivenhoe Dams. A subsequent class-action lawsuit found in favour of 6800 residents in their claim against the Queensland government, Seqwater and Sunwater, and accepted that the dam operators had failed their duty of care to manage the dams before and during a “biblical” deluge. A potential billion-dollar payout has been mooted and appeal is underway.

The Flood Inquiry criticised conflation in some media reports of two separate issues: “whether there was non-compliance with the manual strategies and whether it caused unnecessary flooding” and was careful to articulate that “no dam can guarantee the prevention of flooding in areas downstream of it.” Cook laments the focus on dam operations, writing “For floodplain dwellers, Wivenhoe Dam remains a talisman if operated correctly. If human error could be proven, the myth that a river could be controlled with technology could be upheld.”

As well as legislative and physical changes, there has been work to address the technical language used to describe flood events. Hoban explains there has been a “big push” to change the terminology from commonly used labels such as a “1 in 100 year” to the preferred “Annual Exceedance Probability” (AEP). AEP refers to the likelihood of a flood of a given size occurring in any one year, and is expressed as a percentage. A 1 percent AEP flood, therefore, has a one-in-a-hundred (one percent) chance of being exceeded in a given year.

This is important as the ‘flood literacy’ of a community is dependent on a shared, commonly understood language. The notion of a ‘1 in 100’ year flood makes for a strong headline but is open to misinterpretation: if you lived through Brisbane’s last major floods, in 1974, you could be forgiven for not expecting another one only 37 years later. As historian Margaret Cook explains in her book, A River with a City Problem, “There is still little societal understanding that there is a 1 percent chance of a major flood occurring in any given year.”

We use a single word—flood—to describe the inundation of land that is usually dry. Despite this, a ‘flood’ can be caused by rainfall, ocean tides, storm surges, tsunamis, seismic activity and breaches in barriers such as levees. When caused by rainfall, floods can vary due to the quantity, intensity and distribution of the rain. Flash floods occur when rainfall is heavy, intense, sudden, and falling in a relatively small catchment that is usually dry. When rainfall occurs over a longer timeframe and falls into a larger catchment, floods can build more slowly as they make their way through the drains, creeks and rivers of the catchment. Slow-moving river floodwaters like this can be joined by water from a rapid flash flood. Floods can also vary depending on the geometry of the space through which they flow.

All floods are different.

Cook reminds readers that “floods are part of the natural hydrological patterns” of rivers, which “shrink in drought and expand beyond their banks in times of flood”. A flood is “only a disaster when something is built in its path.”

Some 1.2 million people live within the 13,500 square kilometre Brisbane River catchment. Even after the intensive coverage, public inquiry, ongoing class-action and changes to flood risk mapping since 2011, it is difficult to know the extent to which residents of Brisbane, Ipswich, Toowoomba, Grantham and beyond feel a connection with the catchment.

Similarly, the Brisbane River floodplain is home to more than 280,000 people and is claimed to be the “most flood impacted area in Australia”. It is estimated to have the “largest number of existing buildings of any floodplain in Australia”. Three-quarters of those—some 100,000m of building—are located in Brisbane, and the majority are residential.

Speaking earlier this year, Cook suggested that in Brisbane “a lot of people don’t know their river,” and it’s understandable that there are varying levels of community awareness. Kirby acknowledged a disconnect between his professional knowledge and personal experience. In choosing a home, he’d been drawn to an interesting inner-city location with the river only a hundred-metre stroll away. It wasn’t until he spent time talking with colleagues after the flood that he became aware of the amount of development that had occurred in Brisbane since the 1974 flood. Yet when walking through West End streets that had been submerged, Kirby readily admits “I had to pinch myself that it had really happened.” There were no visible signs that the flood had occurred, nothing to suggest the river was anything other than a benign backdrop to a restful park.

In locations across Brisbane there are few hints to the watery foundations from which the city grew. One of the earliest European maps notes land now occupied by the Botanic Garden as ‘marshy’ and ‘swampy’. The creek that would one day be subsumed under ‘Creek Street’ is boldly delineated.

Maps from the 1850s and 60s show the chain of “lily-covered waterholes” that flowed near the location of the Brisbane Cricket ground, The Gabba. One of these was a popular swimming spot for the Brisbane’s Aboriginal people, with “whirling waters” being one translation for Woolloongabba, from which the suburb takes its name. In his collaborative work researching and mapping First Nations sites, Dr Ray Kerkhove has confirmed the importance of Brisbane’s southside waterways as sources of fresh water and food, as well as recreation.

Another waterway ran through the land now occupied by South Brisbane, flowing through six blocks behind present-day South Bank. Around the corner another creek ran roughly parallel with the river in West End, through the land now bisected by Montague Road, before exiting to the river at Orleigh Park, the spot only a 100 metres from Kirby’s flooded house.

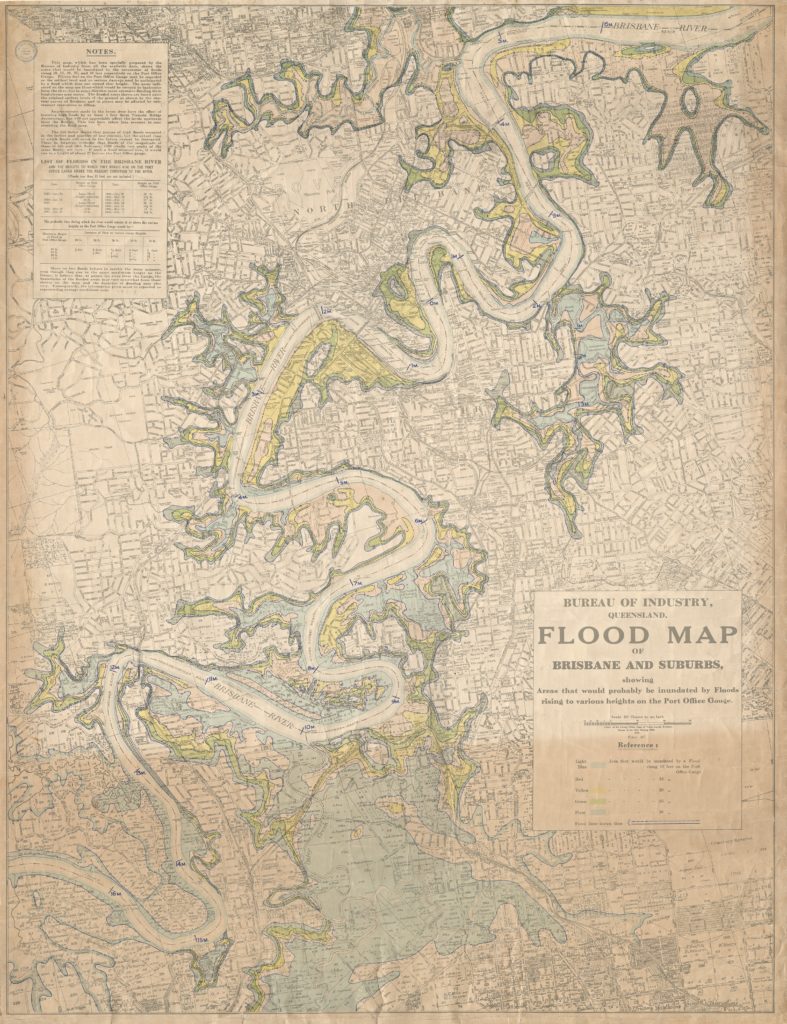

A beautifully drawn and rendered map from 1933 shows areas of Brisbane “that would probably be inundated” by floods of varying intensities. Within the coloured zones now lie a large part of the city’s CBD, the buildings of its cultural precinct, dotted along the riverfront next to South Bank, and swathes of residential, commercial and industrial development. In 2008 the Queensland Government overturned a controversial proposal for North Bank, citing traffic impacts and flooding concerns resulting from a platform extending more than 70 metres into the Brisbane River. The equally controversial Queens Wharf development is now rising on the same site, with a linear waterfront park of lawn and pathways that are designed to flood.

What’s harder to find on this map are the old creeks, corseted into concrete and buried underground. To what extent does an absence of water from everyday life contribute to a lack of collective consciousness of waterways, natural systems and floods? Is it a case of out of sight, out of mind?

David Uhlmann, Queensland President of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, observes that ongoing uptake and acceptance of green infrastructure and water sensitive design since 2011 has resulted in positive project outcomes at the local level. ‘Daylighting’ of creeks, naturalisation of drains, integrated detention and bioretention are helping to manage overland flow and localised flooding, in conjunction with providing broader environmental and community benefits, as is the Oxley Creek transformation, which is working holistically within the Brisbane River’s longest tributary, and largest creek catchment in the city.

Davidson has also observed a change, suggesting that both the Davidson Street Creek Restoration project, facilitated by Healthy Land and Water, and Brisbane City Council’s Stones Corner Hanlon Park project, demonstrate that people value their local waterways and understand the role they play. The Hanlon Park project will see a section of Norman Creek returned from a concrete drain to a naturalistic waterway. This will make visible one of the many “creeks…swamps…lagoons and wetland” that were once a “distinguishing feature” of southside Brisbane.

Since 2011 councils across Queensland have undertaken enormous effort to model and understand flood risk, and to make that information available to homeowners. Similarly, the QRA has worked to coordinate activities across government, the not-for-profit sector, community, business and industry to build resilience before, during and after natural disasters. One community has chosen to relocate and build again, out of its floodplain, a decision not as achievable or palatable elsewhere. Dam operations have been interrogated, but without a nuanced discussion of the complexities of living in floodplains. The state sets admirable targets which local councils must navigate complex competing interests on the ground.

Our choice to settle in a particular landscape has always involved an assessment of the risks and rewards on offer. Reasons for staying in a place are also complex. Cities, communities and natural systems evolve and entwine over time. To talk about flood risk is not just to discuss hydraulics, but equity, memory, connection, and place.

Earlier this year, Turrbal and Jagera man Shannon Ruska addressed a gathering in Woolloongabba, in the same location where his forebears camped, hunted, fished, and swam. In welcoming visitors to Country he issued an invitation: “No matter where you come from in the world if you don’t know who you are as a person, you should find it”.

So who are we, those who call this ‘most disaster-affected state’ home? Are we happy for the water to rise again, as long as it goes back down? When does it become too much? And how will we decide?

Amalie Wright is an architect, landscape architect, and Director of Landscapology, which helps connect people and landscape using design to build a bridge between the rigours of science and engineering, and the delight of spending time in nature. She is an AILA Fellow, former Board Director, Queensland President, and member of the Creative Committee for the 2020 AILA virtual conference Land-e-Scape: Reset – Towards Healing.