“Resort tourism meets rainforest feral”? It’s time to rethink the tropical city

Like many cities in the tropics, Australia’s Cairns is booming. How it manages that growth will determine whether it becomes an exemplar of urban sustainability in turbulent times, or a cautionary tale.

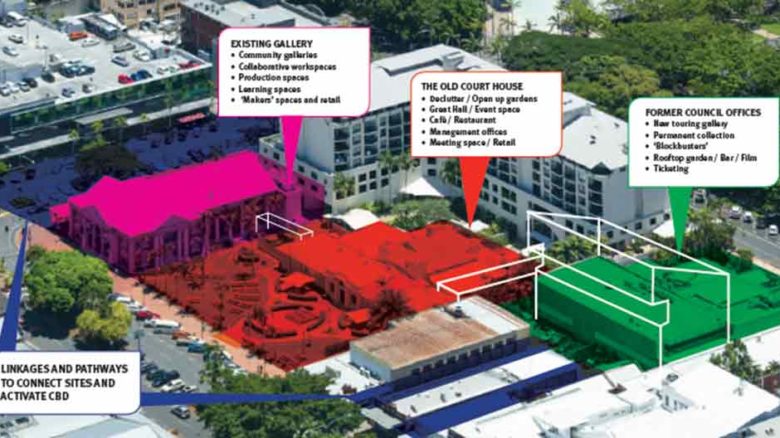

In recent years Cairns has transitioned from a modest trading port to a glamorous tropical tourism destination. Today, the continuing rapid expansion of development across the city makes it regional Australia’s fastest-growing property market. Its two universities are expanding, as are its convention centre and naval hub facilities. Along with a masterplan for a new gallery precinct, these developments will all further increase employment rates that are already growing at more than three times the national average. Tourism, which has long been significant for the city’s economy, has seen unprecedented recent growth. Cairns is on the move.

The city had anticipated it needed a robust plan to manage change. Adopted in December 2017, the CairnsPlan 2016 could have helped the city leverage funding and energy for a new vision of a locally distinctive tropical urbanism. However, while the plan promotes “a city in a rainforest,” this vision is arguably less significant than the ready financial investment of private developers. Indeed, the urban transformation occurring in Cairns today shares a pattern of coincidental circumstances that enabled the celebrated transformation of Melbourne’s urbanity, through development of its laneways.

As the CairnsPlan 2016 claims, “it is a balanced plan that encourages growth while maintaining the qualities and characteristics that make the Cairns region special”. But what are the dangers? How can the economic development of Cairns be guided, to serve a wider positive growth in the region? What are the industries and services, skills and knowledge that are needed to deliver this?

Cairns as a growing farm town, in 1925 Image: State Library of Queensland

Cairns of yesteryear, as a budding tourism centre

Cairns of yesteryear, as a budding tourism centre

Tourism is still growing, thanks in part to the Cairns Esplanade Image: Bahn Frend

Tropical Urban Design Lab

Lisa Law of the Tropical Urban Design Lab (TUDLab) in James Cook University sees these questions as shared by many colonial settlements, which are grappling with shared post-colonial responsibilities for their modified and remnant indigenous landscapes, unique demographic histories and contemporary cultures.

Aboriginal peoples have occupied the land on which Cairns is built for many millennia. James Cook landed in 1770 and various colonial explorers have visited and mapped it since. The discovery of gold in 1872 led to the largest non-indigenous settlement in Far North Queensland.

“As a place colonised by Europeans, the dune ecosystem of what is now Cairns city was bulldozed and built over. We still have a legacy of importing ideas for buildings and the public realm,” says Law. “This is what the Lab is trying to do, build and share knowledge around climate responsive, place-based design strategies, to help show off the fact that we live in this amazing urban place, nestled between the Great Barrier Reef and World Heritage listed rainforest.”

Another thing Law draws attention to is the city’s distinct demographic. “Cairns has a larger-than-average indigenous and Torres Strait Islander population, and long-standing connections to places like Papua New Guinea and other parts of Melanesia, as well as Southeast Asia, China and Japan.” In some sense Cairns has more in common with Papua New Guinea, which is just a 40-minute flight away, than the rest of Australia.

It is also no longer just a destination for retiring southerners. As Law notes, “Our population is aging, like everywhere else, but we get people who have come on holiday here and decide they just must move back.”

Part of Law’s work to understand the urbanism of Cairns is about understanding its suburbanism. In her study of tropical backyards, she looked at the preferences and practices of a very mixed community from various European backgrounds, South East Asian and many more. Planting was of particular interest. “When we started the community garden here at the university we thought we should get the Papua New Guineans and other tropical migrants to show us how to grow their non-European varieties of things like spinach,” says Law. “The available retail seed varieties for growing domestic plants are not really suitable for here. Everyone tends to have a lot of failures. If you get your tomato seeds from Papua New Guinea there’s a good chance they’ll grow better.”

CairnsPlan2016 generic greening Image: Cairns Regional Council

A $176m expansion is proposed for Cairns Convention Centre Image: Advance Cairns

Proposed Newgallery Precinct Image: Cairns Regional Council

Tropical botanic gardens could play an important role in tropical urban development Image: Alaska Dave

Biodiversity under threat

Beyond backyards, the source of plant material has huge implications for the success and variety of public realm planting. Over a decade ago, the many advantages of cultivating little-known tropical species, principally in improved approaches to sustainable multi-layered agriculture, were explored in Traditional Trees of Pacific Islands: Their Culture, Environment and Use. The domestication of little-known “traditional trees” offers enormous opportunities. As the book described, “Typically, a high degree of variation is found in traits that can be captured in new cultivars to greatly enhance yield and a range of quality attributes.” Law’s research reveals that considering species local to Queensland rainforests, for use in urban planting, offers similar climate-specific horticultural potentials.

The role of tropical botanic gardens is critical for tropical regions, which notably contain most of the planet’s biodiversity. Law acknowledges that there is a rapid change in land-use and forest conversion throughout the tropics. This is a problem because there are still so many species to be discovered and they are likely to become extinct or at least extremely rare before they can be documented. When it comes to deforestation, Queensland leads Australia, clearing land at rates that have only recently been legally curtailed.

Maintaining the genetic integrity of site-specific species populations is one task. However, it is recognised that “assisted migration” of species that are vulnerable to climate change, and creative local collaboration with governments, NGOs and indigenous people to make more species available in cultivation, is a valuable parallel task that can change the appearance and experience of cities.

Such migration of plant species, whether in response to a changing climate or other factors, brings with it important cultural considerations. As Lisa explains, “If you look around at Cairns, many urban plantings are from across the tropical world from the Pacific to Asia and beyond. I always think it must be odd if you come to Cairns from the Pacific. There is a rich plant symbolism and many cultural reasons why you plant a specific tree there – such as, if someone has passed away. But here, we’re just using those trees as city plants, regardless of such considerations.”

The use of specific plant species to reflect past associations and memories, as well as engender new ones, is not something that the CairnsPlan 2016 considers. As a high-level planning document, its imaging is simply that of a generic greenery. It will be up to project designers to explore and persuade clients of the value of plant selection considered at many levels, including that of cultural significance.

Expanding the range of local species available through nurseries (a horticultural ambition throughout Australia with volunteer-led and industry initiatives) is an ongoing effort. The Council of Heads of Australian Botanic Gardens recently recognised the need for a National Strategy and Action Plan for the Role of Australia’s Botanic Gardens in Adapting to Climate Change. “We should be working with our herbarium at James Cook University, to consider what rainforest plants we can bring down and grow as vines, for example,” explains Law. “What are the drought-resistant, flood-resistant plants that we can grow in the middle of traffic medians?” This is a potential growth area for research and the nursery industry as well as our indigenous rangers, building on local knowledge and making green infrastructure adaptable to Australian tropical wet and dry conditions.

Law acknowledges the very interesting history of Cairns Botanic Garden, but its focus on exotic species and recreation does not help promote what is possible with local species. Rather, she sees the challenge of local species planting being taken up by others. “There is a very interesting company here called Abriculture. The Abriculture team have a shared vision and an understanding of the important role tribal ecologists play in modern ecology, sustainability and global food security.’” They are doing work with People Oriented Design. A recovery centre for brain injuries in indigenous communities uses specific plants for recovery connected to those communities.

Munro Martin Parklands Masterplan. Image: Cairns Regional Council

Outdoor culture at the redeveloped Munro Martin Parklands. Image: Cairns Regional Council

Nightime occupation of the Parklands has changed. Image: Cairns Regional Council

Artists impression of vine arbours in the parklands. Image: Cairns Regional Council

Uneven development

While Cairns is undergoing massive physical change and has flourishing grass-roots design practices and community cultures, there are tensions. As long ago as 2005, the popular award-winning development of Cairns Esplanade was greeted as a highly desirable example of cosmopolitan urbanism. One review described it as “a quintessentially Queensland space: resort tourist meets rainforest feral, a little Gold Coast glamorama, some backpacker chill and a substantial dose of spectacle.” Law certainly sees the new Cairns Esplanade as quite different to other linear foreshore reserves, dotted with family picnic spots. Yet as she points out, it was also criticised for precipitating the moving on of illegal campers and indigenous people, replaced by what she describes as “a plasticity that is usually associated with south-east Queensland developments.”

Opened this year, award-winning Munro Martin Parklands is a more recent example of urban transformation, with effects similarly both positive and less so. As Law observes, it represents a desire to be “the arts and culture capital of the north. We are renovating our landscapes so that we have world-class performing arts facilities, as many others are doing. So now you can go and see ballet and opera and other types of performance that we didn’t have access to before, while sitting outside in beautifully landscaped spaces with vines over the walkways.”

As the first public park in Cairns, it is a significant site for many. For a long time, it was a space for the city’s growing homeless population. Now they are displaced and locked out of the Parklands at night. It is worth noting that Cairns has the highest rate of homelessness per capita in the nation. Rosie’s food van used to serve the homeless at Munro Martin Parklands, but was relocated and faces new calls to move it from the city centre entirely.

Certainly not all homeless or rough-sleepers are indigenous. The large indigenous population is located throughout Cairns. “We do have an indigenous population, but I wouldn’t say that the public realm has spoken to them much at all,” says Law. She does, however, point to the recent completion of Shields Street, which now has indigenous art through it as part of “beautification works”. This is an achievement in a context where even acknowledging histories of Aboriginal presence can be seen as conflicting with other histories in urban environments. With the development of Reconciliation Action Plans by many organisations, including the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, greater communication and inclusion is expected to bring mutual benefits from future works.

To have urban change that genuinely reflects a city’s society, communication between the many groups that call it home is more vital than ever. “I like being really involved with communities, industry and local government because it makes my research better and more targeted” confides Law, “but it means negotiating the labyrinth of contested issues and influences that always accompany urban development. There can be a lot that is confidential or partially understood.”

While the jury may still be out with regards to the CairnsPlan 2016, without doubt the contributions of many interested people, across universities, NGOs and other organisations will help inform the strong investment and interest in Cairns and in tropical Australia. Australian tropical cities like Cairns are in an excellent position to lead carefully informed scientific and design research in this dynamic environmental region.

In doing so, Cairns has the potential to be an exemplar for the growth of other tropical cities, at a time when tropical cities across Asia, Africa and South America are growing more rapidly than anywhere else. This is what makes the challenge of sustainable development in tropical cities a matter of urgent global importance.

–

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at The University of Adelaide, and is a registered landscape architect of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects.