Three planning strategies for Western Sydney jobs, but do they add up?

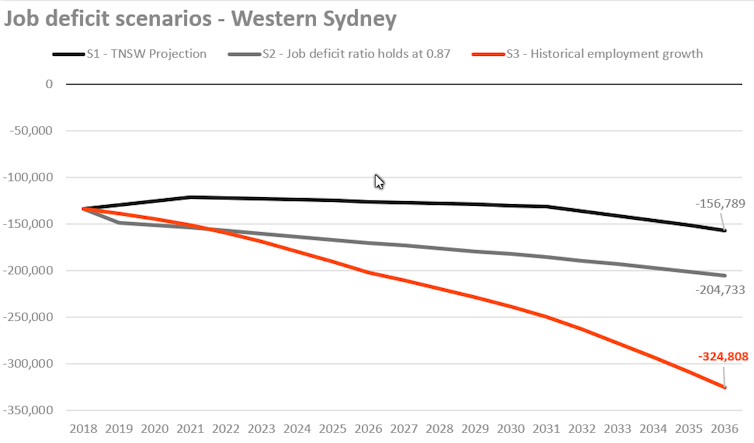

There’s a lot of spin when it comes to jobs creation in Western Sydney, which is currently on track to have a shortfall of 325,000 jobs by 2036. Will new planning measures really create the thousands of jobs promised to the area?

The problem of not enough jobs in Western Sydney has been in the public spotlight for half a century. At the same time, though, record immigration levels and cheap housing on new residential estates way out on the urban fringe have fuelled growth in the region’s labour force. Long-distance commuting by car is one consequence.

Our estimate in our newly released research reports is that by 2036, should nothing change, Western Sydney’s 1.5 million resident workers will confront a shortage of 325,000 jobs. This will mean a daily outflow from the region of over 560,000 workers. And that would be a planning disaster.

The good news is that governments are aware of the problem. Perhaps they have been sensitised by increasingly close election results in Western Sydney seats.

Governments are looking to three strategies to solve the problem – although none has yet generated a permanent job. A COVID-19 recession has arrived to make start-up even more difficult.

Plan A: Western Sydney Airport

The first strategy is the Western Sydney Airport. A first runway is planned for 2026 and a second around mid-century.

The federal government and impact statements say a fully operational airport by 2063 will generate 88,000 airport jobs. It will also create 25,000 jobs on an adjoining business park and a further 29,000 jobs elsewhere around Western Sydney. If realised, these impressive numbers would make a major contribution to the region’s job needs – but not for a long time yet.

Plan B: Western Sydney Deal

The second strategy is the Western Sydney Deal, which includes the promise of what it calls an aerotropolis. This is the idea an airport can attract high-value enterprises to its vicinity. A Western City and Aerotropolis Authority (WCAA) has been established with the promise of 200,000 jobs across a new Western Parkland City.

It’s a hugely ambitious project. Many have questioned both the idea of an aerotropolis and the possibility of one in Western Sydney yielding 200,000 permanent jobs.

Plan C: Metropolis of 3 Cities

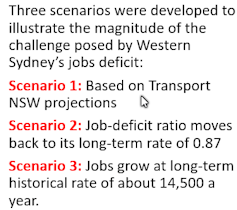

The third strategy is the set of plans in the Greater Sydney Commission’s A Metropolis of Three Cities. The plans divide Western Sydney into two cities, the Central River City and the Western Parkland City, broadly the inner (and older) and outer (and newer) districts of the region.

Commendably, the commission stresses the need to integrate population, housing and job targets into Sydney’s land-use planning. The commission aspires to the 30-minute city as a daily travel range for every Sydney household.

The commission estimates 817,000 extra jobs are needed from 2016-36 to accommodate metropolitan Sydney’s labour force growth. Western Sydney’s share of this total, according to Transport for NSW, is 49.6%, equal to 405,000 jobs.

The commission’s plans contain forecasts of job growth in each of the metropolitan area’s strategic centres. For the Central River City, centred on Parramatta, the commission nominates ten strategic centres and predicts a baseline growth of 71,400 jobs for 2016-36. For the Western Parkland City, the fringe suburbs plus the airport, the plan proposes only three strategic centres and predicts growth of only 24,000 jobs for 2016-36.

So, the total growth in jobs from 2016-36 assigned to Western Sydney’s strategic centres is 95,400. That leaves over 300,000 jobs to be found by 2036 from growth somewhere else in Western Sydney.

While the commission acknowledges the importance of the airport and aerotropolis for jobs in the Western Parkland City, it fails to attach job targets to these ventures. This makes sense, given the uncertainty about the level of jobs generation that will flow from these projects. And neither of these ventures is expected to become fully operational until after mid-century.

Absent airport-aerotropolis jobs, the commission nods in the direction of greenfields employment areas to provide more than 57,000 jobs over the next 30 years. A fancy science park to accompany a new residential estate at Luddenham is to deliver 12,000 jobs. But little detail is provided in either case.

Huge risks and uncertainties remain

So each of the three interventions carries risk. The airport is being constructed at a time of great volatility for air travel. There is a high degree of uncertainty about the nature and volume of air traffic in the longer term. In any case, the airport’s big benefits won’t come until the 2050s.

The spillover effects from the airport into an aerotropolis are untested and, like the airport, can only ramp-up around mid-century.

Then, to get 50,000 jobs from greenfields industrial areas in Western Sydney would mean a monumental shift from a pattern of transport and logistics investments with low job creation that have dominated equivalent sites over the past decade.

There’s not much here to give confidence that a Western Sydney planning disaster will be averted. The region’s chronic jobs deficit is central to the problem. More detailed planning, rigorous assessment and generous resourcing are all urgently needed.

The Centre for Western Sydney has released three reports on Western Sydney’s growing jobs deficit. You can read the reports here.

Phillip O’Neill, Director, Centre for Western Sydney, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()