Not just future suburbs: Planning our food future

Energy, water and creaking public transport are familiar concerns for our growing metropolitan areas. But we rarely talk about food. A research project entitled Foodprint Melbourne identifies this as a dangerous blind-spot.

Australia’s population is growing. This is particularly the case in its five largest state capitals, which have some of the highest rates of population growth in the OECD. This brings with it a range of challenges, from stabilising energy and water supplies, to managing urban densities and housing affordability. But larger populations also mean more mouths to feed. A research project from the University of Melbourne entitled Footprint Melbourne, makes a powerful case for adding food security to the list of Australia’s urban growth challenges.

“It became clear to us there there was an issue with Melbourne’s food supply in relation to what’s grown on the city fringe, otherwise known as a ‘foodbowl’,” says Dr Rachel Carey, Foodprint Melbourne’s lead researcher. “Because Melbourne, like so many other cities in Australia, is rapidly growing, we wanted to find out what’s growing on the city fringe, and how we can ensure significant food supply in future – especially given the pressures of climate change and the declining natural reserves that underpin food production.”

To do this, the university has released three reports that outline the state of play: Melbourne’s Foodbowl (2015) outlines where things are produced, Melbourne’s Foodprint (2016) asks what it takes to feed a city, and Melbourne’s Food Future (2016) posits how planners might strengthen and increase the city’s food production capacity.

Exponential growth advertised on Melbourne's urban fringe. Image: Foodprint Melbourne.

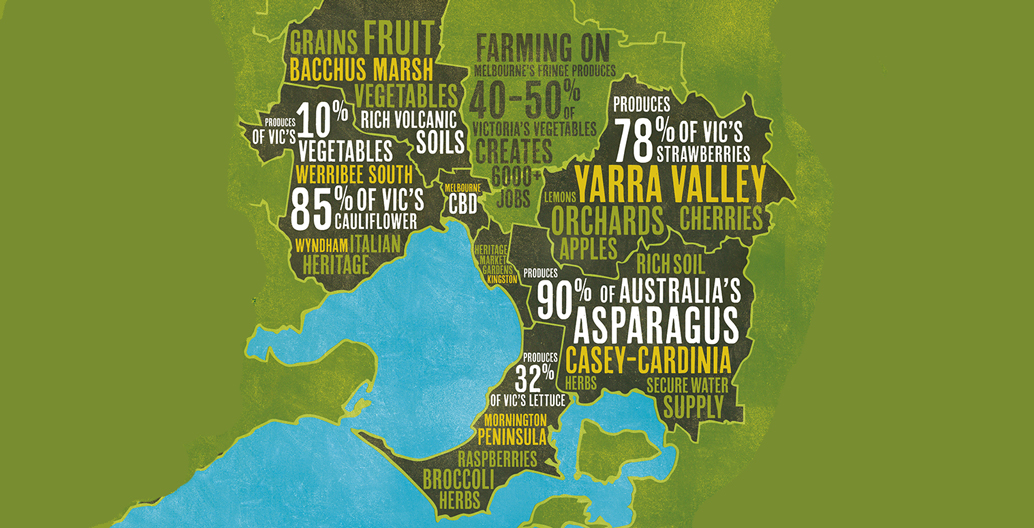

An overview of the produce grown in Melbourne's foodbowl. Image: Foodprint Melbourne.

A dirt road in the peri-urban suburb of Keilor in Melbourne's outer-west. Image: Google.

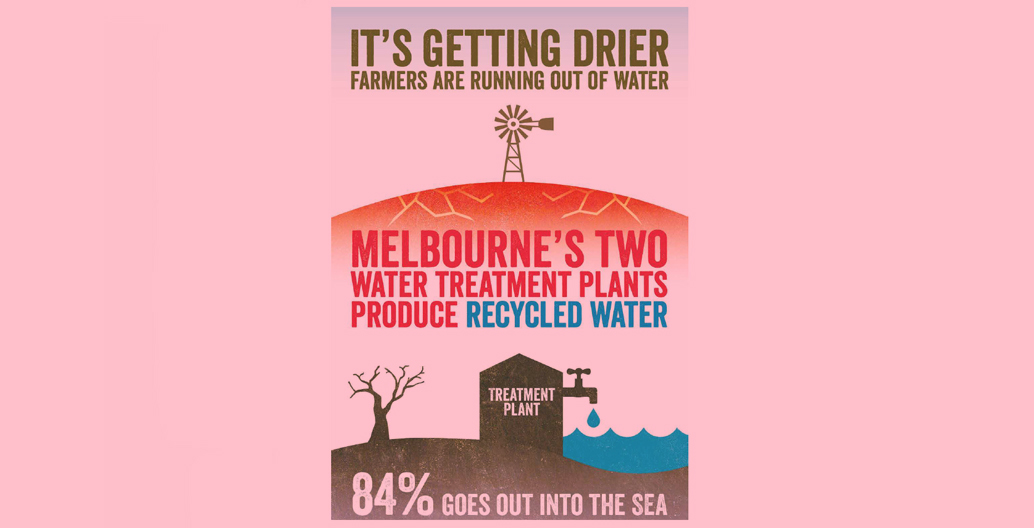

Melbourne's treatment plants pump out 84 percent of water to sea.

The inherited foodbowl

Historically, agricultural opportunit defined where colonial settlements were located. As such, most Australian cities are located near a primary water source, and are surrounded by fertile agricultural regions that, over time, developed into the peri-urban fringe the most Australian cities have today. As noted by the Melbourne Food Future report:

“The area surrounding the city of Melbourne has long been a rich source of food. The peoples of the Kulin Nation skilfully managed the abundant resources of the place now known as ‘Melbourne’ for tens of thousands of years, living on the diverse, seasonal food supply. Europeans introduced vegetable gardens and fruit orchards, and in 1839 the city established its first produce market. Market gardens grew up along the ‘sand belt’ to the south of the city, and orchards and dairy pastures to the east. The city fringe was established as an important foodbowl providing fresh food for the growing population. Melbourne was virtually self-sufficient in vegetables until the Second World War, but by the 1950s, rapid post-war expansion was pushing the market gardens further out of the city and displacing the city’s farmland.”

Melbourne’s foodbowl currently has the capacity to produce 41 percent of Melbourne’s total food needs, with 47 percent of the vegetables grown in Victoria. National and global food markets have picked up the deficit in food production, which has brought with it a false sense of security.

“All of the natural resources that underpin food supply: Land, water and fossil fuels, are declining,” says Carey. “In recent decades, thanks to a complex global food supply network, we’ve been able to get food from anywhere, and we’ve overlooked the importance of local food sources.”

The peri-urban fix

By 2050, Melbourne is predicted to house 7-8 million people, and Foodprint Melbourne estimates 60 percent more food will be needed to feed these people. Arguably, these people will also want to live in affordable areas, which currently sit on the city’s fringe. So too, does Melbourne’s foodbowl.

“Food is an essential need alongside housing, water and transport,” says Carey. “Urban planners have a big role to play in determining food supply systems. Now that’s going to mean ensuring a city relies on a diversity of food sources, which is going to require keeping some fresh food sources close to the city.”

In other words, state governments need to resist perpetual urban sprawl. “We may need to consider a new mechanism of planning, specific to areas of food production. A food zone if you like” says Carey. While most states have existing land use provisions to protect farm land, these have been historically weakly protected at the city’s fringes. Victoria legislated a ‘green belt’ around Melbourne in 2002, yet Melbourne 2030 has since been breached and transgressed on multiple occasions. Bit by bit the state has rezoned the fertile urban fringe, as a short term sop to housing demand.

And that demand is showing no signs of abating. The city’s outer-western suburb of Wyndham Vale is Australia’s fastest growing suburb, growing by 7 percent each year. It sits in a productive peri-urban agricultural zone, with its neighbouring suburb of Werribee South growing 85 percent of Victoria’s cauliflowers. It’s also surrounded by burgeoning housing estates such as Point Cook, Tarneit and Sanctuary Lakes. As such, the development community has are invested in transforming agricultural plots into fully-fledged suburbs. A recent farm sale in Wyndham Vale fetched $95 million.

“Stabilising land prices is the nub of the issue when it comes to preserving Melbourne’s foodbowl, but of course it’s a tricky one,” says Carey. “We need a hard urban growth boundary, because farmland on the city fringe shouldn’t be seen as housing estates in waiting.”

In Vancouver, a city with very similar liveability metrics to Melbourne, the government of British Columbia earmarked specific areas across the province that protect agricultural land. Known as agricultural land reserves, this facet of planning policy gives farmers, developers, and citizens certainty when defining the urban fringe. And of course, keeping the agricultural urban fringe viable reaps benefits for everyone.

“We need to look at rebuilding local and regional food systems to make a more resilient food system overall,” says Carey. “There’s resilience in diversity, of supply chains, of outlets, and in the sources of a city’s food supply.”

Productive farmland in Werribee. Image: Mattinbgn

Flying over Melbourne reveals the urban fringe creep in the city's foodbowl. Image: Jeff Pang

Outer-suburban estates in Point Cook, Melbourne.

Farmland in Keilor, Melbourne.

The climate question

It’s clear that extreme weather events will have a sizeable impact on Melbourne’s agricultural productivity, while extremes abroad will mean that the inter-connected global food network may not always be there for us. As Melbourne’s Food Future notes:

“…becoming dependent on ‘somewhere else’ to meet growing shortfalls in food supply is likely to be an increasingly risky strategy, because the global and national food supply is facing similar stresses to Melbourne’s foodbowl”.

During the millennium drought, Victorian farmers in Werribee came close to running out of water, with groundwater and river water allocated to less than 10 percent of normal levels. This led to a recycled water scheme feeding treated water from Melbourne’s Western Treatment Plant to the affected farms, which Carey cites as a literal farm-saver: “Had we not consumed produce grown from recycled water during that drought, some farmland production on Melbourne’s fringe would’ve collapsed – Werribee would’ve been one of them.”

But even with hindsight, infrastructure is still playing catch-up. To this day, 84 percent of treated water from Melbourne’s Western and Eastern Treatment Plants is disposed of at sea.

“We need to invest in the infrastructure to store recycled water, and we need to build the infrastructure to get that water around to farmers,” says Carey. “Essentially as we may have less water to grow food in future, we’re going to need some long-term planning to deliver foodbowls, close to treatment plants that can grow food during droughts.”

So where to from here?

By 2100, Australian agricultural production is estimated to drop significantly. Depending on the severity of climate change’s effects and the manner in which farmers adapt, this research estimates a drop of between 17 percent and a whopping 92 percent. Relying on the same agricultural practices that worked in the 20th-century clearly isn’t going to produce a resilient 21st-century foodbowl, nor are the consumption habits of the previous century.

“Consumers, schools and government all have a role to play,” says Carey. “We need to reconnect with local farmers wherever possible, and ask more questions about where your food comes from.”

The affluence of our capital cities has meant that food security hasn’t registered as a top-order issue. This research is an invaluable tool, to help us start taking this issue seriously. “The question of a resilient foodbowl isn’t necessarily asking whether it will happen or not, but what it takes to make it happen,” says Carey. “Are we going to wait until another crisis, or are we going to do the long-term planning before we hit another one?”

—

Dr Rachel Carey is a Lecturer and Research Fellow in food policy and sustainable food systems at the University of Melbourne. She leads the Foodprint Melbourne project, which is investigating what it takes to feed Melbourne and the role of Melbourne’s foodbowl in increasing the resilience of the city’s food supply.