Hostile pave-over: development threatens fragile eco-systems along Queensland’s coast

As the Queensland Government continues to threaten environmentally reckless development on a fragile wetland, perhaps the choice is not between economic and environmental interests, but between short-term and long-term thinking.

Government obligations to protect internationally-significant environments are being challenged by government-led economic development programs. A stark example of this tension is currently playing out within the Toondah Harbour Priority Development Area, in Moreton Bay. It is the site of significant development plans, while also a designated Ramsar wetland. Ramsar wetlands are considered to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention, part of an intergovernmental environmental treaty established in 1971 by UNESCO.

The property development company Walker Group Holdings has been engaged as government’s preferred development partner since 2014. Yet progress so far has been slow. A stalled 2017 submission was finally withdrawn, and recently the group resubmitted a new development proposal, which looks set to meet further resistance.

The listing of the site for accelerated development by state government, along with subsequent development visions, has been vigorously opposed for years by an articulate local community, as well as independent expert organisations such as Birdlife Australia.

This example is just one of many fragile landscapes under threat along the coast that forms a pattern of hostile attitudes to complex natural systems. Yet at the same time, there is a growing tourism incentive to reconsider large-scale property development in new ways – not just another planning battle, but perhaps a design opportunity.

This incentive to do things differently is driven in large part by popular and press attention to tropical regions, which are increasingly recognised globally as important natural ecologies. Migratory bird flyways are a fitting symbol of vital intercontinental links. As the home to unique threatened flora and fauna, as well as strong indigenous cultures, the tropics and subtropics are ready for mature reconsideration of historically exploitive practices.

Queensland’s unique coastal environments have featured regularly in the news for some time, most recently with the visit of Prince Harry and the Duchess of Sussex to Fraser Island. The Prince met with Butchulla elders and community in remote Pile Valley, where a ceremonial welcome preceded rededication of the Forests of K’gari to the Queens Commonwealth Canopy Project, protecting over 200,000 acres of the island. Other, less happy news includes the ongoing decline of the Great Barrier Reef and battles over Adani’s Carmichael coalmine, among general concerns over the impacts of global warming and sea level rise, recognised in recent State Government program funding.

Queensland’s tropical and subtropical coasts have been characterised, perhaps caricatured, by canal, resort and leisure development from the 1950s, then unique within Australia. There is an impressive list of Australian land development firsts, attributable to the Gold Coast, including time-share properties, strata titled apartments, the first gated community and masterplanned estate, the first theme park, first mechanised water-skiing park, as well as the first private university. It may be that the tropics liberate cautious temperate minds.

Toondah Harbour artists impression Image: The Walker Group

Foreshore Park artists impression Image: The Walker Group

A proposed 200 berth marina at Toondah Harbour Image: The Walker Ground

Contested development projects continue to be proposed, as planning tools evolve to variously encourage and control them. However, visions of demonstrably new potentials and markets is lacking, with proposals illustrating predictable generic views. ‘Artist’s impressions’ are accompanied by consultant reports that identify important impacts, yet offer assurances of mitigation and the representation of a strictly limited scale, to reassure both concerned locals and experts.

Landscape architecture practice TCL has recently been appointed lead consultants developing a masterplan for Fraser Island’s Central Station, while Aspect Studios has been part of the team responsible for The Spit Master Plan – 201 hectares of conservation open space and public foreshore, just south of Moreton Bay. Early open consultative approaches in these projects, with various communities including Indigenous groups, is made by exploratory designers and suggests more exciting, less predictable outcomes than those prepared in advance for consultation.

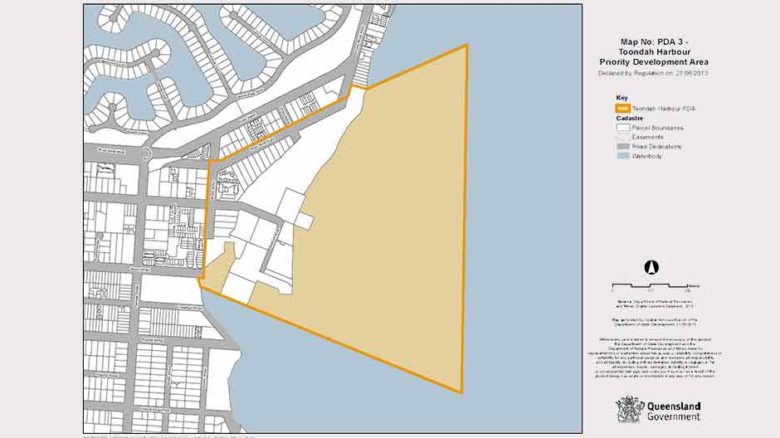

This then is the background to the proposed development at Toondah Harbor, which is subject to a range of protections, including obligations as part of the Moreton Bay Ramsar site. However, at the urging of the local Redland City Council, it was declared a Priority Development Area (PDA) on 21 June 2013 by the state government. This was not long after the Economic Development Act 2012 (ED Act) replaced the Urban Land Development Act 2007 (ULDA Act) in February 2013.

Adoption of the Toohdah Harbour PDA Scheme made no mention of the Ramsar Convention, focusing on economic benefit: “The development of Toondah Harbour will boost tourism and create new business opportunities and jobs while supporting existing businesses and providing the local community with better services and facilities.”

Of the 31 declared PDAs across Queensland, 10 are waterside or coastal sites and four of these encroach into water or across waterways. However, Toondah Harbour PDA includes by far the largest area of water. Of 67 hectares, 17.5 are over land and 49.5 within Moreton Bay itself. It is also the only PDA within a Ramsar wetland or other wetland of internationally recognised significance.

A “History of the Toondah PDA Consultation” with an annotated chronological list of significant decisions and actions is provided by the very active community forum Redlands2030 Inc. It includes extensive hyperlinks to news reports, submissions and other documents, which collectively evidence sustained objection to successive development plans. Just over a week ago, Redlands2030 celebrated the 25th Anniversary of Ramsar and welcomed back vulnerable Bar-tailed Godwits and Eastern Curlews. With around 400 people in attendance, a variety of speakers explained the site features and significance including several Birdlife Australia members.

Toondah Harbour was designated a Priority Development Area in 2013.

Toondah Harbour stretches out over a an important wetland of internationally recognised significance.

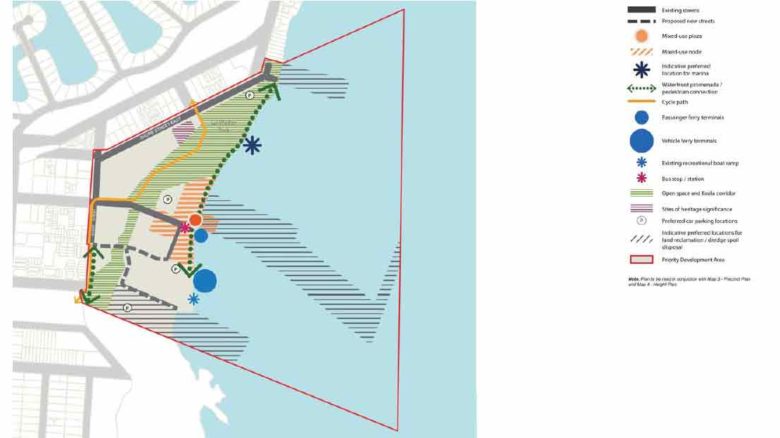

Toondah Harbour master plan Image: The Walker Group

Toondah Harbour structure plan

Birdlife Australia is recognised as a leading authority on the ecology and conservation of Australia’s shorebirds. Their 2018 submission on the latest proposal from Walker Group Holdings repeats objections from 2016 and 2017, labelling it a “clearly unacceptable” action.

Australia’s climatic zones are a mosaic of interlaced areas, rather than the simple divisions defined by global latitude, with Queensland’s coast showing particularly fine distinctions. Appreciating this subtlety can assist us in understanding the complex fragility of interconnected land- and sea-scape systems and the ecosystem services upon which humans as well as specific flora and fauna rely. Two different state government departments recognise the importance of ecosystem services: the Department of Agriculture and Water Services and the Department of Environment and Energy. Both intrinsic values and market values of resources, good and services are acknowledged.

The Queensland Government also recognises the business potential of ecotourism. With the global rise of sustainable tourism, and high-end environmentally rich experiences, such as those to be had through glamping, who might be expected to occupy and enjoy a future artificial marina development? The early resorts of the Gold Coast circumvented prohibitions on foreign ownership of residential properties by making them part of mixed-use and integrated land developments. Perhaps some thought is being given in PDAs to concerns about foreign property investment in Australia and the more recent, as well as potential future projected regulations. Restrictions to foreign purchasing of existing houses have recently recorded significant impacts. The Toondah development application describes the project as “tourism and recreation” rather than residential.

The development logic of Toondah Harbour consistently plays out arguments of economic priorities over environmental ones. However, perhaps a more appropriate binary, is between short-term and longer term benefits. Considered in this light, ecological value and market value might meet, in new ways, beyond the current battle lines.

Australia’s growing tourist and real estate markets place value on the context for housing, as much as the material or architectural quality of the building stock itself. Arguably, architecture is building design, which already considers and responds to this context. Fundamentally, there is questionable ongoing economic benefit in developing land in a way that will threaten the wider landscape qualities that attracted development in the first place.

Unique marine and coastal conditions that harbour rare bird, terrestrial and sea life make them desirable places to live or visit, capitalising on the rise of eco-tourism. While legal and ethical obligations must inform decisions on the development of Toondah Harbour, enlightened self-interest and historical insight could bring a wider and future-looking positivity to how more carefully designed proposals can make a strong business case, with transparent cross-species benefits. Such a plan is yet to be devised.

–

Dr Jo Russell-Clarke is a senior lecturer in the School of Architecture and Built Environment, Adelaide University, and is a registered landscape architect of the AILA. Following study at RMIT University she worked initially in a small Melbourne practice on award-winning projects and subsequently for a multinational firm with a focus on landscape infrastructure and suburban subdivision. She is a frequent contributor to a range of professional and academic journals.