For Dr Greg Moore, defending living heritage isn’t about the past, but protecting our future

Since the 1980s, Australia’s National Trust movement has worked to celebrate and protect the country’s living heritage by identifying and recognising Significant Trees. As the University of Melbourne’s Dr Greg Moore explains to us, these trees are more important now than ever before.

For more than three decades, Dr Greg Moore has worked with the National Trust of Victoria’s Register of Significant Trees to raise awareness of Australia’s arboreal heritage and protect it, if necessary, from the axe. As Dr Moore sees it, the register is formal recognition of what many of us already feel about the value not only of the especially unique specimens that make it on to it, but trees generally.

“When it comes to trees, people tend to understand that they’re important, even if they haven’t articulated or rationalised their attitude,” Moore says. “Trees are markers and totems in our lives and in our landscapes — most of us have some sort of connection with them.”

One example of this deep well of often hidden affection might be the City of Melbourne’s ‘email a tree’ initiative. The council set up dedicated email addresses for each of its trees in 2013 so that citizens could report problems. Instead, the trees were inundated with a deluge of fan mail.

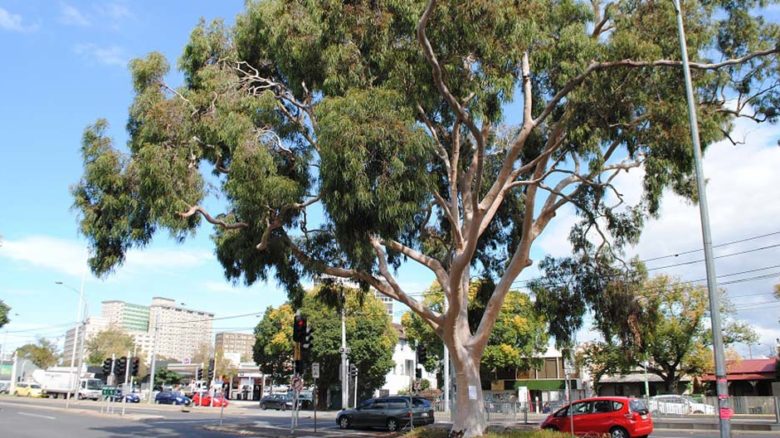

The Golden Elm on Punt Road in South Yarra is a local personality and received the most emails out of any tree in Victoria. As Dr Moore points out, it’s been on the register for almost as long as the register has existed. “If work is done anywhere near that tree, we will hear about it immediately,” he says. “And we won’t hear about it from just one or two people — sometimes hundreds will let us know.”

The Golden Elm on Punt Road is listed as significant trees for its “ its aesthetic value, for its contribution to the landscape, and as an outstanding example of its species”. Image: Jessica Hood.

The National Trust movement set up the Significant Tree Register partly in recognition of the fact that if built heritage is deemed important enough to save, often much of what lends it value is the landscape that surrounds it, as much as the buildings themselves. As Moore says, “The most important component of those landscapes from my perspective, the one that gives real ambience and a sense of permanence, is the trees.”

For a tree to make it on to the register, it needs to be nominated. That nomination could come from experts or the general community, but ultimately it will be the Register of Significant Trees committee that decides whether or not a tree makes the grade. Criteria for registration covers a wide range of qualities, and can include things such as singular size, rarity, and historical importance. As Dr Moore explains, though, while the net might be cast wide, the committee’s assessment protocols are stringently adhered to by necessity.

“We try and maintain the integrity of the trees on the register so that if someone knows that a tree is on the Register of Significant Trees, they know it is a very special tree.”

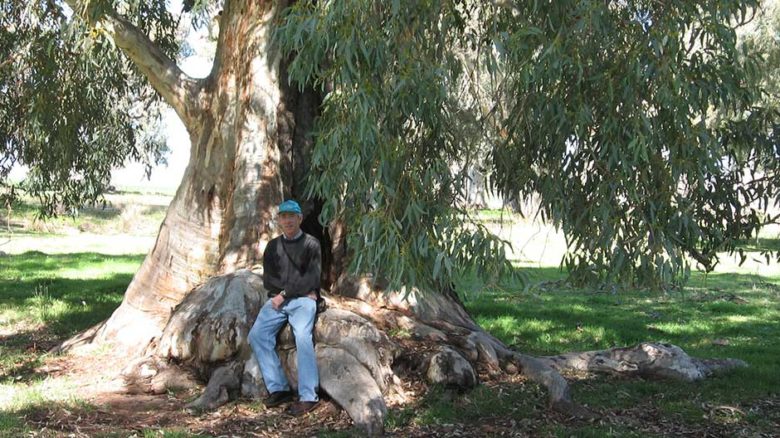

Dr Moore's view looks out across 400-year old river red gums in Burbank Park in Keilor. Image: supplied

Dr Greg Moore has volunteered and worked with aboriculture organisations for close to 40 years. Image: supplied

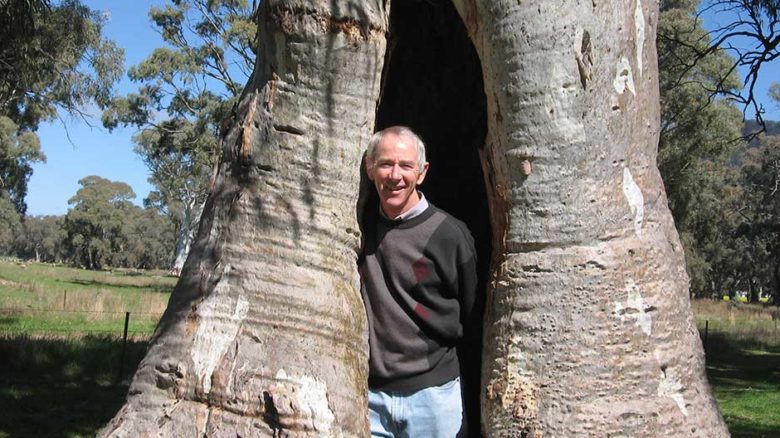

Messmate Stringbark, Eucalyptus obliqua has been the focal point of some of Dr Moore's research work. Image: Arthur Chapman

The register doesn’t bring with it any legal protections, so ultimately it is just this perception and the National Trust’s sway that will protect registered trees, unless of course the relevant local government body is then inspired to accord it protection under a planning scheme. Nevertheless, the Trust has been remarkably successful in its mission of protecting our living heritage, despite the lack of this legal shield. Dr Moore says that of the roughly 1600 registrations, covering nearly 30,000 trees, to the Trust’s knowledge only seven trees have been removed by developers.

Sometimes the Trust might resort to “name and shame” in instances where registered trees are at risk and take the prospective felling to the media, but Dr Moore believes a big part of their success is attributable to gentle and constructive advocacy.

“We’ll go to a developer before going public and say, ‘You’ve got a really great tree here. We hear that you’re thinking of removing it. Have you considered these alternatives? Do you understand the significance of the trees of the landscape?’,” he says. “Not infrequently, the developers will work around the tree. If you can talk beforehand, very often you get a better outcome.”

The tree is slated to be removed as part of the EastLink freeway works. A petition against its removal has 4,500 signatures.

Recognised as a significant tree but under threat from developments, this 300-year-old River Red Gum in Bulleen pre-dates colonial Australia.

This 100-year-old Lemon-Scented Gum on Flemington Road was the first significant tree recorded by the National Trust in 1982.

Local community banned together to protest the removal of the Flemington Road gum, earmarked to to be cut down as part of the CityLink Tulla Widening road project.

The big problem from Dr Moore’s perspective isn’t necessarily that developers or planners have an active dislike for trees, or that they’re expensive to maintain or work with, it’s just that they haven’t considered them or the contribution they make to a neighbourhood or community.

This consideration isn’t just important for those trees deemed significant enough to make it on to the register. The broader picture shows that within Dr Moore’s home city of Melbourne, as elsewhere in Australia, annual tree loss is severe — he believes the city could be losing as much as 1.5 percent of its canopy coverage every year. This isn’t just a tragic loss for cultural or ecological reasons, but has deeply worrying implications for Australia’s capacity to weather climate change.

“To give you a rough idea, we’re probably going to lose something close to 20,000 trees in the inner west over the next couple of years,” says Dr Moore. “Not because anyone has planned to remove them, not because anyone deliberately wants them to go, but because no one’s thought enough about how important they are to lowering the temperatures on this hotter side of the city.”

Dr Moore places the blame for most of the loss on private infill development and major capital works, such as the West Gate Tunnel.

“That vegetation is not there just for ornamental purposes — the shade that is provided reduces the risks of heat wave related deaths; the canopy cover reduces the effect of the increasingly stronger wind events that we’re having,” he says. “There’s a whole range of benefits. And yet we’re losing vegetation cover when everyone is saying we should be increasing it.”

Working with trees is playing the long game. It is planning for 50, 100 years from now, observes Dr Moore, extending considerations beyond the lifetime of anyone involved in a tree’s protection. It also in some ways forces a necessary consideration of the vital but often-forgotten non-human networks that sustain us.

“People can forget that we are part of the ecosystem — we’re not above it,” says Dr Moore.

“That’s quite disturbing, because if you break that connection at a personal level then you’re certainly putting your health and well-being at risk. But if you lose it as a culture, you’re putting the whole fabric of your society at risk.”

–

Dr Greg Moore OAM is chair of the National Trust of Victoria’s Register of Significant Trees committee and a senior research associate at University of Melbourne, Burnley Campus. He was Principal of Burnley College of the Institute of Land Food Resources at Melbourne University from 1988 to 2007. Prior to this he was a Senior Lecturer and Lecturer in Plant Science and Arboriculture at Burnley from 1979.