Ageing, isolating and unequal: Melbourne’s Chief Resilience Officer on the city’s problems

Building a resilient city is about more than sustainability, says Toby Kent, two years into his role as Melbourne’s first Chief Resilience Officer.

In 2013, the City of Melbourne was one of the first 32 cities picked out of a global pool to join the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities initiative. The idea aims to foster ‘resilience’ among a like-minded group of global cities, including the likes of Sydney, Auckland, Seattle and Seoul.

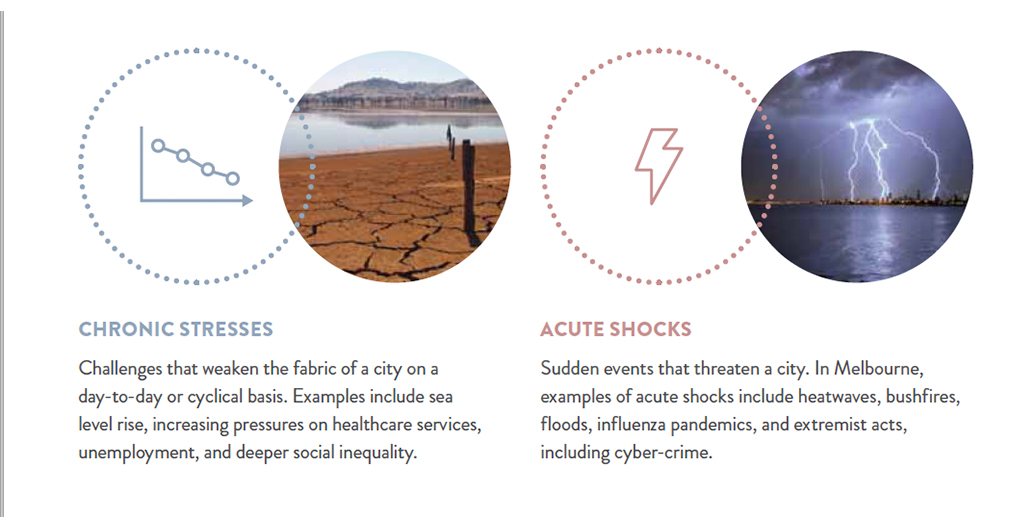

The notion of resilience is understood here to speak to the holistic challenges of urban life that sustainability, it’s close cousin, doesn’t necessarily encompass. Resilience policy-makers speak of “shocks and stresses” to a city that include natural disasters, declining social cohesion, or risks to essential services, among others.

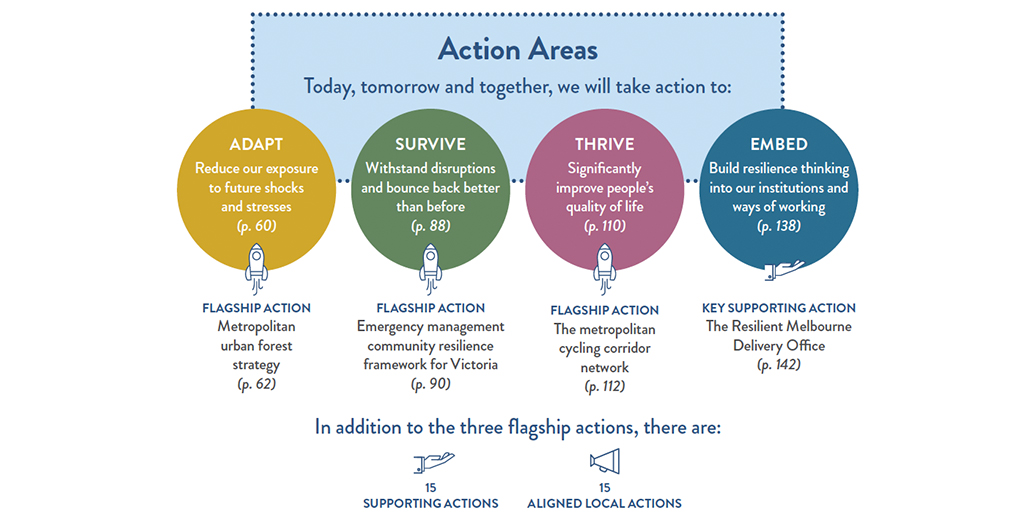

Resilient cities work towards redressing current risks, while future-proofing for impending ones. That’s where Toby Kent comes in, Resilient Melbourne’s first Chief Resilience Officer, appointed in 2015. He oversaw Melbourne’s first resilience document, one that brought together all 32 metropolitan councils, over 1000 people from 230 organisations, and various Victorian Government departments. Melbourne’s plan for the future, it is designed to reduce the city’s exposure to potential shocks and stresses (like climate change), even while it improves its capacity to withstand them and the day-to-day quality of life of its citizens.

Kent speaks with Foreground about what he sees as some of Melbourne’s key resilience challenges and how the city might adapt to deal with them.

Foreground: How would you define ‘resilience’?

Toby Kent: Resilience means thinking about how well things are integrated in a city. It often gets mentioned in the same conversation as sustainability, and an easy example to explain the difference would be Victoria’s desalination plant. Obviously, we still need to continue water-saving measures, which I would think of as sustainability activities. But we also need to acknowledge that things will at times go profoundly wrong and thus we need to have the spare capacity to help us in these periods.

The Resilient Melbourne action plan.

Resilient Melbourne's 2016 strategy document articulating the city's shocks and stresses.

Melbourne's 24-hour public transport on weekends provides more points of access for the outer-suburbs. Image: Terry Chapman

FG: Melbourne’s resilience document talks about “stresses and shocks” that otherwise could be negated in the short-term, politically-speaking. What kinds of stresses and shocks need to be addressed in the current political cycle?

TK: While we have been acutely alert to local and state politics – and the political cycle – we have also tried to develop a strategy that stands apart from it. So I absolutely get the question, but I also think it is important not to be overly tied to those cycles. By its very nature, we know resilience will take at least a couple of generations to achieve.

One of the ways I feel more comfortable addressing this question is to ask: What are some of our immediate stresses? Well one of them is a rapidly growing and transforming population that’s more culturally diverse, with a larger proportion over the age of 65. Alongside that we see ongoing and increasing social inequality based off a range of metrics, such as increasing homelessness, fuelled by the lack of access to the housing market for potential owners and renters. Another interesting one that relates to those issues is the perversity of increasing social isolation within an ever more connected society.

That said, when you take a look at some of the things that are being addressed at a state and local level, you have Moreland Council working towards a zero-emissions economy by 2040, and the Victorian Government’s climate adaptation habitation strategy and renewable energy – all of these are well beyond the three-or-four-year political cycle.

FG: Why do you think it will take generations to achieve this?

TK: On the one hand, the concept of resilience is quite attractive within Australia. There’s something in the country’s psyche where people go, “Yeah, I want to be known as resilient”. But, at another level, there is a certain inbuilt contradiction. Everyone wants to be known as resilient, but few want to be in a situation where they have to demonstrate that. So I question how well equipped Australia really is to be resilient as a nation.

I think the real challenge is resilient infrastructure. A well-cited Productivity Commission report shows that 90 percent of all disaster spending in Australia is spent on response rather than preparedness. So if I marry that statistic with one of your earliest questions, which was well what are some of our shocks that we need to be preparing for today, disaster spending is one of them.

FG: For those involved in the infrastructure space, how would you begin to start implementing resilient principles?

TK: What they can do is focus much more on the interplay between a city’s shocks and stresses. So if you’re building a bridge or train station, you need to think about its holistic integration with the city. Does it meet basic needs? Does it ensure continuity of services when other things fail? Is it a truly accessible piece of infrastructure? As I often say, there’s a reason why the phrase “being born on the wrong side of the tracks” is well-used. It not only symbolises a lack of inclusivity but fosters it as well. So a truly resilient city would build for the bottom 20 percent alongside the 80 percent majority.

FG: Are there any non-traditional infrastructure examples that incorporate this kind of thinking?

TK: Take a look at Resilient Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy. We know there is a direct correlation between people’s access to open space and their propensity to take active exercise. A healthy natural environment has positive benefits to an individual’s mental health. We also know that using nature effectively creates better soil quality and bolsters a city’s ability to manage flood risk as well as cooling the city during periods of extreme heat. The data around this shows that an effective urban tree canopy can reduce the urban heat island effect by four to six degrees.

The work that has been done in New York, particularly around the redevelopment of Lower Manhattan following Superstorm Sandy, sees a combination of nature-based solutions to better protect the city from a wide range of shock events. They’re using this development to create parks where people recreate to drive a greater social connectivity and inclusion, additionally creating artistic programs and so forth. What was really well demonstrated in Superstorm Sandy in New York was its cycling network. Where other transport infrastructure failed, people were still able to get on bikes to either evacuate or to travel to see loved ones.

Public transport resilience – New York's cycling network became of valuable importance during Superstorm Sandy

Manhattan's blackout during Superstorm Sandy. Image: David Shankbone

New York's subway network was out of action during Superstorm Sandy. Image: MTA/ AP Photo

FG: Other cities in the 100 Resilient Cities network are London, Paris and New York, with varying degrees of greater control of urban services compared to Australian cities. Do you ever wish Melbourne had something similar?

TK: It would be, at times, fabulous to have a single and influential point of decision-making. At the same time, it would account for such a huge proportion of the state’s population and budget. So I think it is important that we continue to have a system that recognises the needs of Victoria’s diverse communities and the councils that represent them.

But actually, Australian cities see themselves as having more profoundly different governance structures to the rest of the world than we really do. Although there is the Greater London Authority – which has jurisdiction over large assets and that’s what the Mayor of London gets to command – like Melbourne, London is made up of 32 boroughs and each one of those boroughs are profoundly proud of their autonomy. Paris actually has 120 mayors. Greater Los Angeles is made up of 74 townships.

As with so much of life, there is a certain appeal to greater power, but you’ve got to be careful what you wish for. Most councils in Melbourne deeply understand their local communities – I wouldn’t want to discount the importance of that.

––

Toby Kent is Chief Resilience Officer at Resilient Melbourne. His role involves working across Melbourne’s metropolitan region to develop and implement a resilience strategy that will see Melbourne better prepared to manage the chronic stresses and acute shocks that Melbourne will have to tackle, today and in the years ahead. Prior to joining the City Of Melbourne, he worked with leading Melbourne businesses, including MMG mining corporation and ANZ bank, where he was Head of Sustainable Development. Kent holds a Masters degree in Urbanisation (Housing and Social Change) from the London School of Economics.