Western Australia’s flower power

Western Australia stands at a precipice. As several urban projects redefine the city, HASSELL Perth’s Anthony Brookfield asks if the state’s wildflowers can infuse a distinctly Western Australian sense of place.

Western Australia is blessed with beautiful, diverse and dramatic landscapes. Singular to it are its vast varieties of native wildflowers: each spring the explosion of floral blooms is an international drawcard, with thousands trekking to amazing displays, from the Great Southern to the Kimberley. According to the WA Department of Parks and Wildlife (DPaW), the south-western part of the state alone is home to more than 7000 species of flowering plants.

WA’s wildflowers are central to the state’s identity and culture, and should inform any discussion about it. For indigenous Australians, the flowers signify changes in the seasons. Many exhibit healing properties, providing food and pollen to support a balanced ecosystem.

Recent development however, has impacted the natural environment of Western Australia. While there are still great swathes of untouched land, this development raises the question: How do we ensure we keep a connection to what we truly love about the natural environment?

Coalseam Conservation Park. Image: Australia’s Coral Coast.

Wave Rock Wildflower trail. Image: Tourism WA.

Tourist in featherflowers (Verticordia) wildflowers, near Hyden. Image: Tourism Western Australia.

There is an opportunity to celebrate the uniqueness of WA through design – and this includes ‘leveraging’ the landscape. Perth, in particular, has largely shaken its ‘dullsville’ tag, in part due to the energy and vitality of recent place-led developments, which promote high levels of activation, as well as vibrant public artwork, innovative architecture and transformed nightlife. As part of this transformation designers are seeking to draw upon the unique qualities of the Western Australian environment, creating new spaces and forms that celebrate the state’s rich geology, indigenous heritage, climate, and native flora and fauna.

Perth’s Kings Park is evidence of how well the implementation of native flora can work. The park has over six million visitors a year, who come to enjoy the floral displays, city views and bushland walks. Despite the popularity of the park, there has been limited take-up of native flora more broadly in urban spaces. Native planting has largely been avoided due to its perceived ‘scrappy’ appearance, difficulties in establishment and the perception of onerous maintenance requirements.

There are significant opportunities throughout Perth to inject a sense of ‘soft urbanism’ using our native plants. Soft urbanism is a design approach that twines together landscape and the urban environment to establish a sense of place. Soft urbanism values the landscape, earth sciences and biodiversity. Wildflowers can bring a much-needed ‘softness’ to the urban environment, providing relief from the hardness of our streets and built forms. It can create a valid and valuable point of differentiation – at a local and global level. WA’s isolation and particular brand of beauty has the potential to become a special attractor, one born from the symbolic ‘twinning’ of a wildflower landscape, like Kings Park, and the city.

The weaving of the WA wildflower story into the realms of landscape design, architecture, public art and temporary pop-up interventions is already starting. The challenge is how to do it in a way that has a sense of permanence and feels meaningful.

It is being seen in top-down planning along with bottom-up activism. Since 2013, the public-private project Wildflower Capital Initiative (WCI) – led by Sharni Howe – has advocated for themes of wildflowers, six-season planting and embedding places with the “spirit” of Western Australia. Howe has liaised with a range of government departments, private champions and has gathered a broad range of supporters. Complementing the WCI work are emerging initiatives such as the Historic Heart of Perth project in the CBD’s east end, which endeavours to bring wildflowers into the city, either through direct planting or through interpretative design and public art in key laneways and open spaces.

A recent example of design that references wildflowers is the Fiona Stanley Hospital (designed by Hassell, Silver Thomas Hanley and Hames Sharley). Its dramatic diamond facade is an abstract response to the banksia. The combination of its bold facade and the expansive areas of native planting, many of which are at rooftop level, make this a major public architecture project that confidently positions itself in a Western Australian context.

In major infrastructure projects it has now become a requirement to include design, art and landscape treatments that draw inspiration from the project’s particular locality. Major road projects (including Gateway WA, New Perth Bunbury Highway and NorthLink WA) have all worked hard to reinforce a WA sense of place – expansive native revegetation strategies have combined with nodal floral displays, public artwork and architectural responses imbued with the colours and tones of the WA landscape. Similarly, Perth Airport has been keen to better represent WA, with its choice of planting and use of wildflowers being key to this. It has created a ‘landscape journey’ from the terminal forecourts, along the entry roads and through to the Gateway WA project that links the airport to greater Perth. A Main Roads Western Australia program, Wildflower Way, is currently under development, and aims to radically uplift the landscape experience from airport to city. It is a city-making project that showcases a beautiful, rich and rare landscape of wildflowers throughout key infrastructure corridors. It is a long-term vision, focused beyond the electoral cycle, which aims to establish a truly transformative landscape legacy.

Banksia ericifolia. Image: Gateway WA.

Fiona Stanley Hospital by Hassell. Photo: Peter Bennetts.

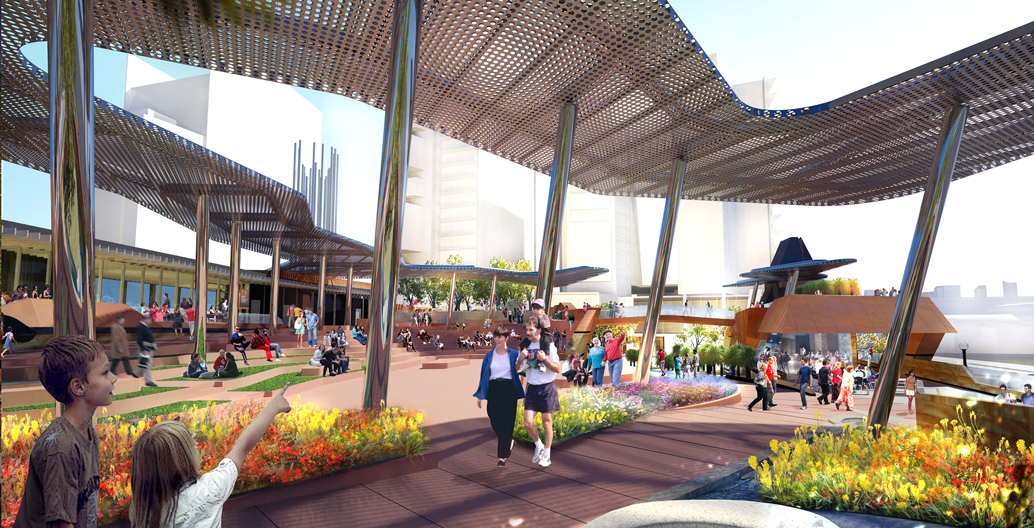

A render of Yagan Square looking west toward its amphitheatre. Image: Metropolitan Redevelopment Authority (WA).

Crown Perth's recent native landscaping.

Another case study of this kind of design approach occurring at the precinct level, and one that I have had direct involvement in, is the new Perth Stadium (designed by Hassell, Cox Architecture and HKS). The project aims to attract visitors, year-round, to the banks of the Swan River. While the facade references the dramatic iron-infused geological strata of the north, the stadium park highlights the spirit of the six Noongar seasons. Expansive swathes of planting combine with a dramatic nature play experience that highlights the flora and fauna of the region. The design team has worked collaboratively with indigenous advisors and artists, environmentalists, and horticultural experts to unlock the potential of this gateway landscape.

Also under construction is the WA state government’s Yagan Square (designed by Lyons Architecture, Iredale Pedersen Hook and Aspect Studios), adjacent to Perth Station. The design focuses heavily on conveying a Western Australian sense of place, with local materials, art, water play and local wildflower planting working together with the intention to create a city environment infused with energy.

There have been other interesting examples of design that wildflowers inform. Many of these express themselves as pavilions, canopies and street furniture placed in parks and precincts – Kings Park, again, being a strong example. Of note, also, is the recent landscape work completed at Crown Perth, which makes a strong attempt to firmly ground itself in the Western Australian landscape.

At the neighbourhood scale, there is a debate surrounding how we treat our ‘leftover’ spaces, in particular residential street verges. The drive towards water-wise planting and using natives is a move in the right direction, with the obvious benefits of reduced water use, creation of habitat and the ability for residents to experience the natural changing of seasons through changes in foliage and floral display.

A movement within government, developers and the design community is taking hold and is breeding opportunities to bring the life, vitality, unique shapes, colours and scents of Western Australian wildflowers into the public realm. There is much to draw inspiration from. It will be interesting to see how well WA’s spaces and places realise this potential as the current and emerging generation of artists, designers, developers, horticulturalists and planners seek to express and reinforce a Western Australian sense of identity.

––

This article first appeared in Future West, a biannual publication that addresses the need for a conscientious debate about architecture, planning, culture, and society across Western Australia and beyond. It looks towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point.

Anthony Brookfield is a Perth-based landscape architect, and is a principal at HASSELL Perth.