WaterLore: what might drylands teach us about living with less water?

The ‘mapping’ of two iconic Australian waterways, the Murray Darling and Cooper Creek, reveals vital stories about resilience in the face of scarcity.

Images are powerful. They are capable of telling complex stories. Even if not exactly universal, images can communicate across cultural boundaries, opening dialogues and enriching understandings and interpretations of the world around us.

In late December 1968, just shy of seven months prior to astronaut Neil Armstrong’s ‘giant leap for mankind,’ the Apollo 8 mission sent an image home from space that changed forever the way we see our planet, and in the process helped to strengthen a burgeoning environmental movement. Of course, this was not the aim of the American space program. In 1961 the Soviet Union sent the first man into space, and the USA was desperate to catch up. The Apollo missions may have ostensibly been a quest of scientific discovery, but they were also an elaborate interstellar Cold War pissing contest.

In many ways, the ‘space race’ and the Apollo missions were a multibillion-dollar failure. Getting to the moon first did not nip the Cold War in the bud, and as American geographer Denis Cosgrove persuasively argued in his 2001 book, Apollo’s Eye, “Its most enduring cultural impact has not been knowledge of the Moon, but an altered image of the earth.” This change in perception came about largely through the distribution of two key photographs of earth as seen from space: Earthrise from the 1968 Apollo 8 mission, and NASA number AS17-22727 (which became known as the Whole Earth, The Blue Planet, or The Blue Marble) taken in 1972 from the final Apollo flight, Apollo 17.

In response to Earthrise, New York Times journalist Archibald MacLeish observed in an article published on 25 December 1968, “For the first time in all of time men have actually seen the earth: seen it not as continents or oceans from the little distance of a hundred miles or two or three, but seen it from the depths of space; seen it whole and round and beautiful and small.”

The effect of seeing the earth as both valuable and vulnerable was even more pronounced in image AS17-22727. As Ursula K. Heise puts it in her Sense of Place and Sense of Planet, which traces the history of the environmental movement and the awareness of the planet as a single ecosystem, “Set against a black background like a precious jewel in a case of velvet, the planet here appears as a single entity, united, limited, and delicately beautiful.”

The Blue Marble image in particular was a kind of cartography – photographic evidence of what had only previously been postulated by cartographers in globes – the earth in all its spherical glory, suspended in space. So it is no real surprise that this image was so quickly co-opted for various causes, for mapping has always been a political activity.

As English historian of cartography Jerry Brotton points out in A History of the World in Twelve Maps, “Mapmakers do not just reproduce the world, they construct it.” In other words, cartography always serves an agenda – or the exploration of one – and the detailed, large scale maps featured in the exhibition WaterLore at the University of Melbourne are no exception. All maps have a story to tell.

WaterLore exhibition viewing at the Dulux Gallery, University of Melbourne.

WaterLore west wall: the Millewa-Murray and Barka-Darling Rivers

WaterLore east wall: the Kunari-Cooper Creek which feeds Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre.

Waterlore reveals both the fragility and resilience of drylands

The ongoing WaterLore project is led by Gini Lee, Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Melbourne, and the recent exhibition was curated by Lee alongside landscape architect Antonia Besa. Their stated agenda is to highlight both the fragility and sustainability of arid regions and learn from drylands.

The exhibition used text, aerial photography and cartography to present knowledge, lore and research gathered from two of Australian’s major river systems: the Millewa-Murray and Barka-Darling Rivers that meets the sea at the Coorong in South Australia, and the Kunari-Cooper Creek which feeds Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre in the northern part of the state, the lowest point on the continent.

The water flow of the first system is heavily affected by legislated human intervention (dams, locks, pipelines and other infrastructure) while the second is, as yet, unregulated. But both river systems are subject to the demands of pastoral and mining industries. As Lee explains, “Arid places may be remote but they are entirely modified by human use.”

WaterLore featured two facing walls of mapping; one for each system. The exquisite graphics of each river system highlight 12 watercoloured ‘hotspots’. These zones are points of intersection between the past and the present, the needs of people (both settler and Indigenous communities) and the needs of the rivers and the ecosystems they sustain.

The hotspots include areas where things have gone horribly wrong, such as Hotspot 5: Millewa-Murray River, Barka-Darling River, Wentworth, Menindee Lakes, where an estimated one million fish died in January 2019. In other places things are going a little better, such as Hotspot 12: Kunari Cooper Creek, Innamincka, Ullyamurra Waterhole, Burke’s Waterhole. Here, where the ill-fated explorer died, permanent waterholes have allowed the Yawarawarka and Yandruwandha Aboriginal people to occupy the land continuously for millennia.

This last is an important point. Lee and Besa state in their aims for the project, “The idea is that in a drying landscape, much can be learned from people who already know how to work with a lack of water tied to inconsistent weather, economies and politics, both locally and beyond.”

Overwhelmingly, those with this knowledge are the Indigenous people who have lived in the arid zones of Australia for untold centuries. Yet both the data gathered for WaterLore, and the way it is presented, is rooted in Western scientific and didactic traditions.

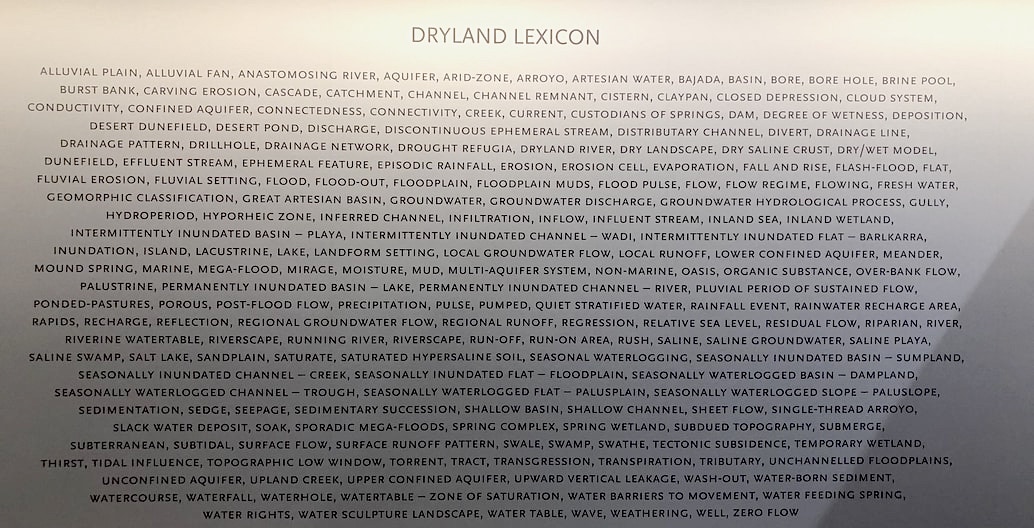

A ‘Dryland Lexicon’ covers the end wall between the mappings. Here, in alphabetical order, are terms from many disciplines speaking to both the subtle and the radical differences of landform behaviour and water influence on the very small and also enormous scales of complex dryland systems. To their credit, the curators acknowledge that a greater Indigenous voice – or indeed many different Indigenous voices from the length of these vast and varied waterways – is something that needs addressing in a subsequent stage of the project.

In fact, the ongoing nature of the project is key. WaterLore as a whole is designed as a provocation, a starting point, a visual and textual lexicon in progress, not a closed book. Lee and her team hope that their research into drylands water knowledge will lead to new research, heighten awareness about the cultural importance of our waterways and inspire future design projects. As they explain, “At hotspots water stories are being told with increasing urgency by people with knowledge of the culture, nature and wise management of these places, where imagining possible actions towards alternative futures may be influenced by design.”

WaterLore map detail including close-up 'hotspots'.

WaterLore map detail including close-up 'hotspots'.

WaterLore research table and aerial photography wall.

The aims of WaterLore are timely, as we find ourselves in the midst of an ongoing climate crisis characterised by increasingly unpredictable and extreme weather, as much as by increasing temperatures. We are all now living in emerging potential arid zones.

We urgently need to come to terms with the fact that clean, fresh water is a precious and finite resource, something that should be cherished, not literally flushed down the toilet. Ironically, photo AS17-22727 – an image which did so much to excite concern for fragile ecosystems – may have exacerbated our wasteful attitudes to water. Seen from space, the abundance of life-giving water on earth is what dominates the image; we live on a blue planet, precious and rare in the infinite reaches of space.

But if you look closely at Africa, the only continental landmass clearly pictured, it is more brown than green. Large portions are dry and rain starved. Thanks to the instant digital cartography of Google Earth and its satellites orbiting our planet, we can now see the earth from space from any angle, anytime. Swivel round from Africa across the huge Asian continent and the vast swathe of brown continues. It even jumps the Pacific and occupies roughly half of the continental US. In fact, of all the continents, only South America is predominantly green.

Focus on Australia and what we see is poet Dorothea Mackellar’s ‘wide brown land’ verdant only at the very edges. As one of the most urbanised countries on earth, with some 85% of us living in cities located in this thin and threatened band of green, we would be unwise to ignore the knowledge of those in drylands under the ‘pitiless blue sky’. We would be foolish to ignore the many nuanced stories told by the maps in WaterLore: tales of struggle and survival.