Killing us softly: the perils of light pollution

Across the globe, the rapid spread of light pollution is having massive negative ramifications for humans and wildlife alike. Meanwhile, the disconnection from the night time sky may have far deeper consequences than many of us appreciate.

The blue light found in most white LED lighting is contributing to a growing catalogue of detrimental biological and physiological impacts on humans, animals, and even plants. Increased light pollution levels and the spread of skyglow in night-time environments threatens entire ecological systems and erasing our ability to see the universe above.

Light pollution threatens our health, and that of our environment

With growing research documenting impacts on species from bats, moths, sea turtles and birds to corals and plants, the detrimental effects of too much artificial light at night are far-reaching and complex. In North America, many migratory birds use the moon and stars for navigation and are known to collide with brightly-lit skyscrapers.

Elsewhere insects spend too much time circling street lights instead of pollinating or procreating and become easy prey for clever apex predators. In recent years, turtle populations have plummeted, partly attributed to the disorienting effects of too much light intruding on nesting sites. Hatchlings use moonlight reflecting off waves to guide them towards the water. Instead, confused by bright urban lights, many head inland and into danger.

Moths and other insects are fatally attracted to city lights and reflections. Photo: Tim Goedhart

Endangered turtle hatchlings head to urban lights rather than the reflection on waves. Photo: Mitch Lensink

Bats are disoriented by urban light pollution. Photo: Serra Galos

Light pollution affects migrating birds. Photo: Barth Bailey

On Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, careful lighting design to mitigate negative impacts on Loggerhead Turtle nesting sites is improving the survival of hatchlings. The lighting scheme employed in these areas is one part of the landmark Sunshine Coast Urban Lighting Masterplan, authored by Adam Carey, dark sky advocate and director at smart lighting design company Elumenarti. The plan marries the region’s planning scheme with an environmental overlay, and is particularly sensitive in nesting zones. “We were mindful that we had to reduce upward and spill light, as well as reduce the visibility of the light itself. We didn’t want to see the glare of the luminaire, so orientation of the light installation was a critically important factor included in that plan,” explains Carey.

In humans, exposure to blue light brings higher risk of chronic diseases such as breast cancer and interferes with melatonin production at night, meaning less restful sleep and higher risk of depression. Both physical and mental health are affected by light pollution.

Obscuring the stars obscures long-held knowledge systems

Tens of thousands of years of Aboriginal star knowledge, which has already had to face the systemic threats of colonisation, is facing renewed threats from light pollution.

“Aboriginal and Islander people make very close observations of everything in the sky,” says Duane Hamacher, a cultural astronomer who collaborates with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to better understand and document the role stars play in cultural practices and knowledge systems. Being relatively predictable and fixed, as well as location-specific, makes stars ideal reference points. The appearance and location of certain stars can foretell when seasons are going to change, and the sky works as a memory aid. Behavioural patterns of particular animals and plants could be correlated to the stars, and this was a way to determine and remember when animals are breeding or migrating, when certain foods are available and climatic conditions, Hamacher says.

Skywatching with a telescope helps see stars increasingly obscured by light pollution.

A spectacular stary sky far from urban light pollution. Flinders Ranges, South Australia. Photo: Jack Cain

Stargazing in remote Coober Pedy, Central Australia. We need to travel far to see stars. Photo: Yong Chuang

This practice can be understood through the maxim, “everything on the land is reflected in the sky,” says Hamacher. “The stars will move around the sky overnight, but they don’t really move in respect to each other for thousands of years, they’re a reference you can always look to. You can look at when they rise and set, and what that means, but also you can look at very subtle changes in the properties of the stars, such as a change in brightness, or colour, or twinkle,” he says. Such observations can even be used to predict the weather. “In the Torres Strait, people say to look at certain butterflies. If the stars look like this and this butterfly is here, it means this weather front is coming through, for example.”

The accuracy of this knowledge is gobsmacking and may help solve contemporary challenges. For example, the use of star knowledge can be used to synchronise climate change, as demonstrated by changes in the dugong hunting season in the Torres Strait. “People would tell me ‘the hunting season happens this week and the sun setting and position of certain stars tell us that.’ But now, because of climate change, it’s being thrown out by several weeks and up to a couple of months in some cases. The elders are concerned” says Hamacher. To make things even harder, in addition to changes wrought by climate change, light pollution is altering what can be observed and shared. And if it becomes harder to see stars and more subtle changes in the colour and tone of starlight are lost to atmospheric pollution, knowledge is lost too.

“All humans have a connection to the sky. People will talk about their first experience of a night sky with a sense of awe and passion. It’s a reminder of the connection we have to the stars, of how important they’ve been for us, as far back as you want to go.” Hamacher uses the example of the Southern Cross. Because of light pollution, some of its stars are becoming less visible. “The most iconic constellation in the sky in Australia has a deep connection to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians and you often can’t even see half of it. This highlights how we’re losing our connection to the sky. We’re so busy looking down at our screens, and even if we were to look up, we couldn’t see anything.”

By tapping into that sense of shared cultural heritage, Hamacher hopes to stimulate interest, empathy and change. He is preparing content on Indigenous stargazing for the national curriculum. “It discusses how science is just as much a part of Aboriginal culture as art or music. That pretty much applies to all human society,” says Hamacher. He also collaborates with communities who want their knowledge to be documented. Given the legacies of colonisation, the genocide and disruption to cultural practices, this can be difficult terrain to navigate as a settler researcher. There are places where very little star knowledge remains to be passed down. In other areas, a lot still exists, but many communities are cautious about sharing knowledge and some is protected or sacred.

Light pollution from LED lighting is detrimental to humans, animals and plants. Photo: Alex Knight

Urban lighting and the extent of polluting light spill is clearly visible from space. Photo: NASA

Existing lighting in eastern Perth, Australia shows different street lighting types. Photo: Elumenarti

Climate change and its toxic causes including light pollution will disproportionately impact First Nations peoples. Their oral histories and cultural practices contain records of scientific knowledge and ways of being in the world that could provide strategies to deal with the consequences of climate change. The historic and ongoing challenge to better engage with and hear their voices is now an urgent priority.

Slowly moving towards regulating light pollution

If we recognise the multilayered benefits of reducing light pollution, the next step is to introduce better lighting design into the public realm. “At the moment public lighting is not undertaken with a great deal of thought,” says Adam Carey. “You only have to visit some of the major growth councils, like Wyndham or Casey in Victoria, Australia. A lot of residents in those developments are having to fit outside blinds because the spill light from street poles is creeping into living spaces and bedrooms.”

There is an urgent need to revisit the Australian building standards, he says. “I have a copy of the 1964 code of public lighting for Australia, which was a re-write of the 1939 code of public lighting. In 1964 they had acknowledged a significant improvement in car headlight technology, and there was the opportunity to take advantage of those improvements to reduce costs in public lighting. When was the last time we looked at technology improvements from 1964 to 2019?” It’s a point he will make at the upcoming International street lighting and smart controls conference in Sydney.

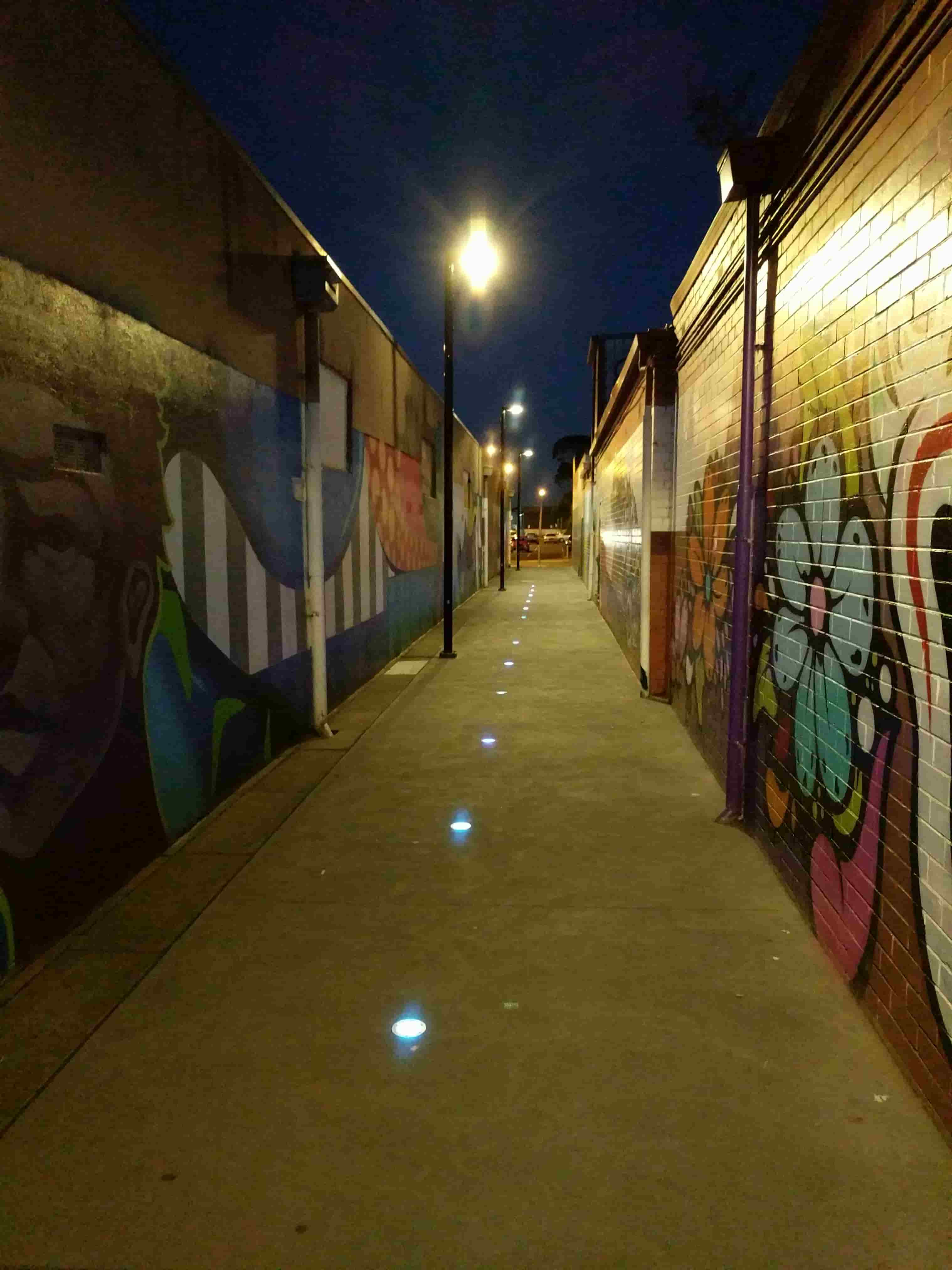

An urban alleyway illuminated with inground and overhead lighting. “The way we incorporate artificial light into the public realm must balance liveliness with sensitivity,” says Adam Carey. Photo: Elumenarti

The way we incorporate artificial light into the public realm must balance liveliness with sensitivity. For the Sunshine Coast, one of Australia’s largest councils by geographic area, this means combining its strategic objective to be a sustainable, smart city, with the challenges that come from rapid development. “I struggle with the concept of making the city skyline a light show, but I also understand that keeping a million visitors in the city at night is significant for economic development and tourism,” says Carey. The visitors he surveyed said they chose the place for its relaxed, subdued pace, and that they definitely did not want “the glitz of the gold coast”. Places such as Singapore’s nature park, Gardens by the Bay, show how artful, sensitive lighting schemes can stimulate economic development and tourism, while promoting a green sensibility. Unfortunately, that approach can’t simply be cut and pasted everywhere, says Carey.

In other places there are pushes for more urban dark sky parks. “We all have an inherent fear of the dark that’s difficult to let go of. We need to see some good examples, we need great landscape architects and forward-thinking developers to explore the design outcomes,” says Carey.

In the coming months, Hamacher and his colleagues at Mount Burnett Observatory are collaborating with lighting manufacturer We-ef to host events during the Australian Heritage Festival at Melbourne’s Ripponlea Estate around shared Indigenous star knowledge and cultural heritage, and the ways lighting technology can help find appropriate solutions. “We-ef tells us that there’s a lot of ways to get the light you want and need, without sacrificing much in the way of what you can see in the sky,” he says.

For Carey, the best examples are currently found in resorts and private properties, which he hopes can spark new ideas for how lighting is designed into the public realm. Less lighting infrastructure would make room for more street trees, which are known to provide the “softly fascinating stimulation,” that has restorative cognitive effects evidenced by better memory, attention span and mood. “I would much rather see trees in an urban development than street light poles,” says Carey.

While the maladies associated with light pollution are many, there are opportunities, through better understanding, to make productive and positive change. A multidisciplinary approach to public lighting that incorporates the varied knowledge and insights from Aboriginal people, lighting designers, ecologists, landscape architects, policy makers and astronomers is required.

Tony Birch, writing in Unstable Relations: Indigenous People and Environmentalism in Contemporary Australia, suggests that in the face of despair brought on by overwhelming negative stories concerning climate change, we need “places or sites of connection where productive and ethical dialogues can be nurtured.” Seen this way, perhaps – as Humacher points out – our shared cultural heritage of the stars could act as such a site and help stimulate a rewarding shift in mindset.

––

Lucy Salt is a writer and landscape architect. Her writing has been published in Meanjin, The Big Issue and Landscape Architecture Australia among other publications.