The parsley, the pig and the farm

Food can be grown in cities and suburbs, as well as in the country. It requires a change, not only in planning policy, but also in how designers and citizens reclaim the commons.

Is it a myth that Australia’s cities are amongst the most liveable in the world? That tag may be true for the lucky people who live close to our capital cities. All our ‘sustainable’ cities are quite nice within their core.

Outside of that core we appear to have failed to make great places worth living in. The planners and the urban designers in Australia are complicit in this other city – the one defined by traffic jams, homogenous character and isolated lifestyles.

The American dream was transposed into the Australian dream: car, freedom and land with a backyard away from the city. This pattern of suburbanisation is stamped on every town, mandated by building codes that replicate the same outcomes.

Farming land becomes ‘future urban’ and then is transformed into sprawl, in a very efficient production system. Given a third of our carbon footprint is related to food, sustainability within our ‘liveable cities’ quickly disappears into the horizon as the food miles increase.

An aerial view of Brisbane’s sprawl.

Driving in traffic for an hour to the town of Beaudesert in outer Brisbane or to Casey City in Melbourne, we see the annual loss of farmland and associated rural landscapes. The rural landscape transforms fast, as we dither over policies for density, boundaries or where to put another 20 million people. While we talk, they build.

It would be a great counter balance to the loss of farmland if the large suburban lots were used for growing food, as occurred during the impoverished inter-war years. But this is not a pattern which dominates our collective backyards.

We could provide north facing food plots within much smaller lots, if we designed better living places. But it appears that dumb houses with dumb streets and landscapes predominate, despite our changing policies for green or smart streets.

Landscape architects have been delegated the role of greening over the suburban subdivision. As designers we often have little to play with, except occasional street trees and parks in drainage ways. We put the parsley on the pig. How are we to change the pig, the suburban subdivision, when so many things conspire against even the simplest idea, such as more street trees?

There is no doubt that landscape architects and urban designers are well suited to changing the pig: they straddle all the useful realms and processes: development, ecology, landscape, streetscape, place, food, rehabilitation, water sensitive urban design. The parsley, the pig and the farm can be designed to co-exist.

We can and should design productive landscapes, from the small to the mechanized scale, into new urban fabric. Lessons from recent projects that I have been involved in as a community activist, designer or planner, point to the opportunities, as well as the pitfalls of putting food back into our planning of places.

Food in the city

At the Jane Street Community Garden in inner-city Brisbane, a community garden has evolved, driven by community energy and funds, and outside of any government agency. Managed by Micah, a not-for-profit organisation, providing insurance and management, residents such as apartment dwellers can rent a garden plot for a small annual fee. They meet, form friendships and share stories of life and death amongst vegetables. In the same neighbourhood of West End, the local community developed The Green Space Strategy, which aims to re-purpose over 11 hectares of unused road reserves, to create green and productive landscapes. Aside from Jane Street, there are community run gardens and verges dotted around the neighbourhood. There are good indications that the commons, one of the last resources that we as a community can control, can be reclaimed by the energy and will of local people.

These types of gardens often start their life as marginal landscapes – guerrilla gardened or created without lease. In the future, governments would do well to tap into this community groundswell for greening neighbourhoods and assist people in creating local food. Creating policies for community gardens, verges and community orchards on streets would be a simple way to start. But land needs to be made available, and given that private land is expensive in the city, it is surely a cost-efficient solution to better use the unused roads and wasted crown reserves that we share.

Jane Street Community Garden is located 5 minutes from the the Brisbane CBD.

The community gardens reclaim unused space between a road and sporting fields.

The Greenspace Strategy was developed by local residents collaborating with local designers.

The Greenspace Strategy aims to reclaim wasted asphalt space, turning these road reserves into productive verges.

The Hampstead Common is a plan to create a hectare of north facing productive greenspaces down an overly wide road.

Food in the suburbs

Fitzgibbon Chase is an inner-ring suburb in Brisbane that has been curated by the Queensland State Government. Aside from producing better than average home diversity, they instigated a food garden for the neighbourhood. Amongst the first home owners, a small group of keen gardeners lobbied the state developer for kitchen gardens and a remnant parcel was designated for The Green Hub. A collaboration with the residents created pathway orchards leading to a community garden with enough space for 20-30 people to grow food.

The original excitement in designing and creating a community garden over time frequently gives way to the more serious endeavour of having to tend and grow the food. Insurance becomes an issue and residents have to find not-for-profits who can cover this. Some people lose patience with birds, possums and other folk who eat their best tomatoes. It is often migrants who have had a lifetime of habitual food production that are the core workers in these gardens. It is also hard to shift the predominant values that attract people to suburban areas: values that favour fast food, a disposable economy and individualism rather than commonality.

The Green Hub is located on a battle-axe block of easement land surrounded by new homes.

Local residents celebrate the opening of The Green Hub in 2013.

The community gardens provide shelter for gathering as well as low vine fences to keep dogs out.

Raised and inground food gardens as well as composting areas and an equipment shed are all shared by residents.

Food in the country

We imagine that country towns have better fruit and vegetables than city folk, but this is mostly not true. Supermarkets and IGA’s all centralise and redistribute food, storing, chilling and eventually sapping a lot of goodness out of produce that may be sold very close to the originating crop. Small towns suffer from a lack of variety of fresh produce, and the best of their own offerings goes to the city or is exported.

The folks in Bingara, a small rural town in NSW had a bold vision: to create a regenerative common which could feed the town by 2020. A dozen or so passionate people formed Vision 2020 and lobbied Gwydir Shire Council to create The Living Classroom: a permaculture-based food farm which could be used as a teaching ground to move farmers and the community to more sustainable practices, and in the process to create local produce to give back to the community.

Progress is dictated by tight resources in the country, but through various initiatives, such as trade-training grants, The Living Classroom has redirected town floodwaters to create a three kilometre chain of lakes and revegetated contour swales, bringing fertility and water back to The Living Classroom and its food gardens. The town’s wastewater is being diverted and cleaned to use as irrigation. Over 200 olive trees were transplanted from a farm that was repurposing land and this created a mature spine for a Mediterranean garden featuring fruits and vegetables: a tribute to the Greek immigrants who came to Bingara to make a new life.

An aquaculture garden, a carbon-capture forest and a kangaroo classroom are all food gardens underway arising from collaborations with university students and designers. Such innovative gardens would be highly resourced in the city, but they are lonely beacons in small rural towns looking for a future as their communities and jobs dwindle. As we move to mass mechanisation and large lot farming, small towns will disappear unless they find alternative economies.

The Living Classroom site wraps around the town of Bingara. The regenerative community farm repurposes a grazed common.

The Living Classroom creates keyline gardens and forest corridors which trap and hold rainwater.

University students from QUT’s Landscape Architecture course spent a week on site.

The Mediterranean garden celebrates Greek heritage.

Food in the future

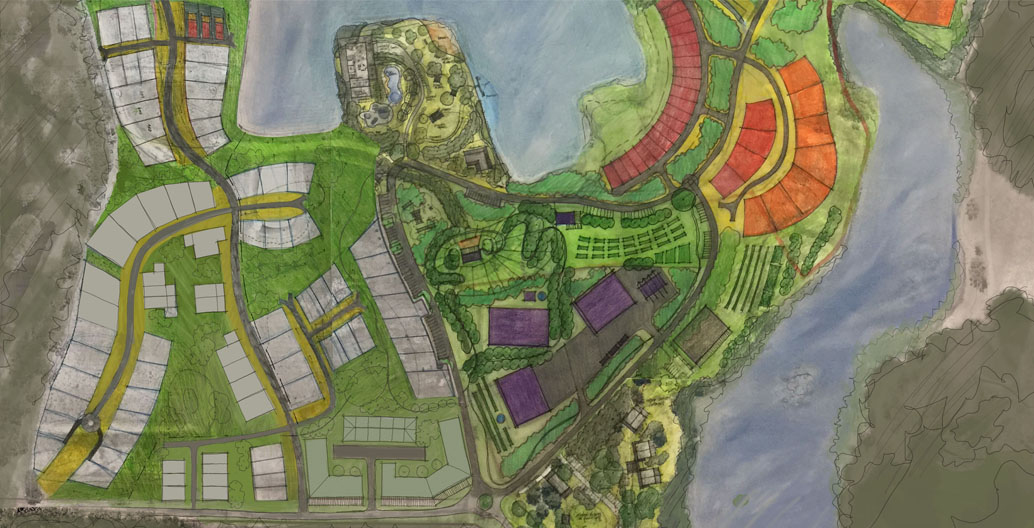

What do our future suburbs offer beyond uniformity, car mobility and individual spaces? Brolga Lakes is a new community being planned on the outer northern fringe of Brisbane city. The level of innovative ideas in this new community could truly disrupt the production of boring suburbs in Queensland if they come to fruition. Approved for a development of 1000 residents and workers, this peri-urban development could create a new type of neighbourhood: neither city, suburb nor country. All of these in function, and none of them in character.

In a conservation agreement with the state, two thirds of the land is to be regenerated to koala habitat and birdlife sanctuary. An interpretive centre will be built to house the headquarters of Birdlife Australia.

The other third of the remaining land is being shaped into a new neighbourhood that will have eighty percent of land in common open space and will be run by its own infrastructure: water tanks under each driveway, a wastewater plant to create irrigation for planting, a solar array farm to provide cheaper power, no pipes and no kerbs to allow the harvest of water. Solar vehicles will be used to collect waste and to share-drive to the shops and train station.

A nursery is being established upfront, repurposing a commercial shade structure to grow local plants for residents and for parks and gardens. The nursery will double as a food garden with a small produce market. The community-title development allows all this infrastructure to be managed by the body corporate, and resources are provided through its levies. The intent is that each resident will be able to pick up a box or two of fresh produce every week at no cost. There will also be plots and common orchards where residents can grow their own, or harvest fruit with their neighbours.

If all of this can be delivered in a place which allows price point entry to a normal suburban home buyer, then it stands to reason it may be very popular.

Like Village Homes in Davis, California fifty years ago or The Ecovillage at Currumbin on the Gold Coast fifteen years ago, these developments can act as templates for a future where food and people are reconnected in one place.

Changing the pig

The suburb needs to be grabbed before it has been drawn: only then can the story of the land, with its culture, soil, water and plants become the framework. Only then could we hope to bring forward any Indigenous land culture.

The lines that form lots and roads are not someone else’s territory: they are the same space that the real landscape inhabits. This bunch of lines can easily mould around the landscape to build on. We can easily draw the spaces for private and public, to craft places rather than subdivisions.

Ten really basic rules could become policy which might drive our placemaking:

- Land, soil and water that is productive or ecologically valuable is mapped and protected. Land that has existing endemic vegetation or valuable soil is mapped and protected.

- All waterways and their climate-change flood catchments are protected.

- Critical values, particularly Indigenous ones, are protected and integrated into development.

- Development is limited to areas outside the above ‘valued landscape’ areas.

- Development must fill into existing developed areas before being allowed to go on the periphery.

- All wasted road, crown lands and verge areas should be mapped and planned for use, before other land is developed.

- The city should be three to six times denser than currently occurs. Housing types should provide for all demographics and family sizes in the same place.

- Work, live, play and food should be possible within a ten-minute walk from where people live.

- Non-motorised transport and public transport become primary modes of movement.

- Industry and retail centres are highly contained, planned and constrained to match the places where people concentrate, and occur beside cultural and event places.

Two-thirds of the Brolga Lakes site will be revegetated to form wildlife reserves.

Placemaking concepts for the site include a central hub of food gardens, nurseries and community orchards.

Homes will be designed to have north facing gardens which will be framed by revegetated lakes.

Productive landscapes continue to elude Australia’s urban areas, despite quite a lot of hype and support. We are too busy to grow and tend vegetables in our homes and our rural areas are being eaten by suburbs. The average age of a farmer is now 65 and our rural communities decline as mass production takes over the small farms. We like to watch how to grow and cook our fresh food on TV more than we care to act on it. At least fruit and vegetables are cool now, and back on the planting palette. A fresh food movement is definitely underway.

We do not need to be distant to our food. It is not good for either our health or our wellbeing. As the environmental writer George Monbiot wrote in his passionate plea for communities to reclaim their commons, we can collectively and at a grass-root level restore our forests, wild areas and our productive landscapes. We do not necessarily need government or private enterprise to always own or control these commons and food spaces, but we do need these systems to provide the space and the policy for food production by ordinary folk near their homes. We need planning and design that builds fresh food into our everyday places, as if it mattered.

—

John Mongard writes about place, landscape and art.