Rising seas, sinking cities: Jeff Goodell on sea level rise & slow-motion civilisational collapse

With sea level rise now taking an increasingly obvious human toll, Foreground speaks to author Jeff Goodell about his new book exploring how communities around the world are responding to this looming catastrophe.

Towards the beginning of his new book The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities and the Remaking of the Civilized World, author Jeff Goodell recounts an interview with former US President Barack Obama, in which the latter disclosed that “part of his job is to read stuff that terrifies him all the time”. At the time of the interview, the two were sitting in a high school classroom in Kotzebue, an Alaskan town in the Arctic that Goodell described as “suffering from a climate-disaster trifecta of melting permafrost, rising seas and bigger storm surges.”

The interview was conducted in 2015. Obama had just become the first sitting President to visit the American Arctic, setting a symbolic backdrop to a new chapter of his legacy, that being effective action against climate change. By the end of the year, the world had settled a cohesive climate change response, after the successive failures of years past, with the Paris Agreement.

The Water Will Come was released in October 2017, almost a year after the election of Donald Trump, and almost two years since that ominous interview in Alaska. In the time since, Goodell’s presumably read a lot of things that would’ve terrified any keen environmental observer: the US is out of the Paris Agreement, an oil baron is Secretary of State, America’s national parks have been scaled back, and Trump’s pick to lead the Environmental Protection Agency not only denies climate science, but has been a “relentless opponent of basic pollution limits”.

In the interview that follows, Foreground talks with Goodell about what he’s discovered about how cities, governments, and citizens around the world are responding to the threat of sea level rise.

Foreground: Given what you know, how did you write this book without falling into despair?

Jeff Goodell: A lot of people talking about climate change talk about the importance of giving people “hope”, or an inspiring message, to keep people onboard. As a writer, I thought about it in a different way, because my job was to illustrate people’s perspectives: their struggles, contradictions, denial, and optimism in real time – essentially to find the human element.

Barack Obama with salmon fisherwomen Kanakanak Beach in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Image: Obama White House Archives.

Barack Obama touring Kenai Fjords, Alaska. Image: Obama White House Archives.

Marathon, Florida pictured after Hurricane Irma. Image: US Customs & Border Protection.

FG: Some of the characters in your book illustrate denial in curious ways. There’s the Miami property magnate you cornered at an art gallery, only for him to tell you that sea level rise didn’t bother him, because by the time it mattered he’d be dead. Then there’s the Miami mayor who points to his Apple Watch and says that technology will save the sinking city. Do you think there’s a strand of American Exceptionalism that keeps people believing they can keep the sea at bay?

JG: There’s certainly an American manifest destiny where some people believe we’ve been put on earth to conquer the territory. You know, “We don’t give up. We don’t retreat. We hold the line” – something that sea level rise very much challenges. But more broadly, with anecdotes like the Apple Watch, that demonstrates a faith in technology where we rely on it to get us out of things. But the idea that we’d just invent some kind of gizmo to keep the sea out is one of the most dangerous aspects of denial because it creates apathy.

FG: You wrote about how some streets in Miami are being raised, while existing buildings stay at the same level – essentially meaning that authorities have the blind hope that one day, homeowners and businesses will raise their structures, too. Isn’t that a bit misguided?

JG: It’s just a ploy by the Mayor to show that they were doing something – that they had things under control. A lot of money is being wasted to make governments seem as though they’re getting things done. Ultimately, the real solution to sea level rise is to move to higher ground… it’s not like you have to invent some kind of gamma ray to kill all the weird creatures coming out of a spaceship. You just need the economic and political will to move cities to higher ground.

.

.

Jeff Goodell. Image: Pernille Aegidius

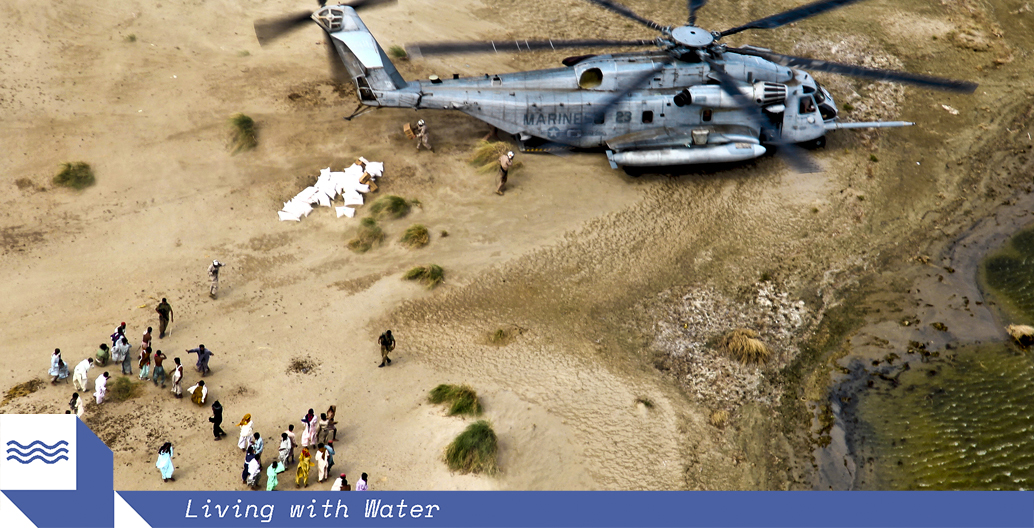

FG: In another chapter, you note that the US Military and intelligence agencies are taking active steps to defend their coastal assets from climate change, not to mention the development of military and intelligence strategies to deal with the consequences of conflict as a result of climate change. But at the US’ executive and legislative levels, there’s still a fervent desire to deny the existence of climate change. Why is this cognitive dissonance so aggressively maintained?

JG: It’s simple: money. About 10 years ago, we had the Citizens United Supreme Court decision that basically reconstituted corporations as people – meaning they had the right to free speech. To make a long story short, it opened up cascades of dark money in our political system, which big fossil fuel interests have taken advantage of, like the Koch brothers. So basically if you’re a Republican in Congress right now, if you inch toward making any kind of acknowledgement of climate change – let alone funding commitments or policy proposals – then you’re putting at risk a large amount of funding for your campaign.

FG: If Congress could snap its fingers and promote sea level rise adaptation now, what could it do?

JG: Well we’d be reforming our National Flood Insurance Program, which is a pool of public funding for populations affected by annual floods. The other thing they could do is reform national building codes, which Obama tried to do, but it was repealed by Trump. That could be supported by an adaptation fund that could help people adapt their homes to sea level rise, funded by a carbon fee. You know, there have been a few progressive senators that have floated ideas like these, but we’re nowhere near close to them in the US, certainly under Trump. We’ll see what happens when he’s gone, but under Trump, we’re going directly backward on climate change adaptation.

FG: Are there any examples of projects around the globe that you point to as exemplars of adaptation?

JG: When assessing adaptation, you need to be looking at geology, building patterns, and politics – every place is different, right? Something that may work in one place may not work in another. In general, what you see in the Netherlands is sophisticated. It’s something they’ve been thinking about for a long time, and that’s why you see things like sand motors where they dump a whole pile of sand on the coast which is then taken by currents to replenish beaches. In a city like Rotterdam, the big idea of living with water – rather than trying to wipe it off – is very significant, because they’ve developed water squares that can hold water while the city is being flooded, then stagger its release when flooding subsides.

But the real truth is that nobody is coming close to grappling with the scale of this problem. You can point to interesting projects in the United States, where they’re raising buildings or putting critical infrastructure on higher floors, but nobody’s moving major infrastructure like roads, airports, or utilities… at best, people right now are doing piecemeal things.

FG: After you wrote this book, the incoming New Zealand Labour government proposed a humanitarian visa for climate refugees – particularly with respect to its vulnerable neighbours in the Pacific. Is this something you could see being adopted by other wealthier states?

JG: No. In an ideal world that would be a fair way to do it, and something that you would think the rich nations of the world would do. In reality, of course, when you look at what’s happening with immigration right now in the US, it’s the hottest issue at this very moment, and in the EU it’s causing all kinds of turmoil. So I think the chances of that happening are slim to none unfortunately. So that brings up the question: where are these people going to go? What are the economic and political consequences of sea level rise?

King tides already inundate downtown Miami with intermittent flooding. This is only set to get worse. Image: B137 via Wikimedia Commons

Villages like Lelata, Samoa are one of many Pacific communities that will be displaced by sea level rise. Image: Kevin Hadfield/AusAID

In Miami at least, the tide turning on financially risky flood-prone developments. Image: Olf:P

Downtown Miami with the detritus of a freak storm event.

The home of the US Atlantic Fleet floods at a higher rate due to seas here rising twice the global average. Image: US Naval Institute

FG: At the start of the book, you said humanity’s slowness to adapt is something akin to a frog being slowly boiled in a pot. What do you think needs to happen to stop us from seeing sea level rise in abstract terms?

JG: More flooding is the only thing that’s going to get more people thinking about it – but it’s going to be the economic story that follows floods that will galvanise people. About a month ago, the credit rating service Moody’s announced that it was going to take climate change adaptation into account when it considers a city’s or a state’s bond rating. So that means that places not taking this into account will have to pay more for money. You can also see this happening with people who are starting to realise that values on their coastal real estate are dropping. I’m most concerned about a lot of people who have their home wrapped up in real estate and don’t have any idea of how much it’s at risk. Politically, you simply could impose the mandatory disclosure of future flood risk of properties for sale, with good standardised flood-risk data. But that’s exactly the thing that vested interests, namely the real estate development industry, don’t want people to have.

It’s very hard, because the big problem with climate change in general, and sea level rise in particular, is that people see it as a slow-motion car crash. Because of our media, and the way that images work, the sexy threats of the moment are always pushing out longer-term issues. That’s happened 10 thousand times since the Trump administration’s election, where in the US, almost everyday we’re on the verge of a constitutional crisis.

But telling a good story has great power, so we need to find narratives that communicate this grave risk. Sea level rise is hugely important, and I’ve tried to connect readers with people who are already dealing with it. It’s a here-and-now problem, and that’s what more and more people will need to realise.

——

Jeff Goodell is a contributing editor at Rolling Stone and the author of five books, including How to Cool the Planet: Geoengineering and the Audacious Quest to Fix Earth’s Climate, which won the 2011 Grantham Prize Award of Special Merit. Goodell’s previous books include Sunnyvale, a memoir about growing up in Silicon Valley, which was a New York Times Notable Book, and Big Coal: The Dirty Secret Behind America’s Energy Future. His most recent book, The Water Will Come: Rising Seas, Sinking Cities and the Remaking of the Civilized World, is published in Australia by Black Inc.