“Humanity needs nature”: Patricia O’Donnell on the UN Millennium Development Goals

It’s been 17 years since global leaders defined the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals – goals the world is yet to achieve. In our final post for 2017 World Landscape Architecture Month, Patricia O’Donnell issues a clarion call for landscape architects to help drive critical global change.

Five colleagues authored the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s 1966 Declaration of Concern focusing on environmental concerns and the future of our profession. Times change, and the complex concerns of today pose a multitude of challenges. The skill sets of landscape architects can contribute to the solutions.

Sustainability, a larger construct integrating societies, economies, and environments, emerged from the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development’s report Our Common Future (1987). Landscape architects have both embraced and disdained sustainability, with works that integrate these aspects or works that – obsessed with form and aesthetics – emphasise alternate values and marginalise our impact. History reveals we missed opportunities in the 1990s to demonstrate the relevance of our profession to the earth and humanity.

I recall a global rumble rising at the millennium, and in response world leaders agreed to the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). These eight goals addressed poverty, hunger, gender equality, health, environment and development with an emphasis on human capital, infrastructure and human rights. The MDGs received limited interest from landscape architects.

A global foment about “starchitecture” and heritage collided in Vienna in 2005. As the International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) Americas representative, I advocated for defining urban landscape character and features, noting that half of city space was landscape (52 percent of Vienna, 56 percent of Washington DC). My contributions and those of colleagues to this global dialogue led to adopting the UNESCO Recommendation on the historic urban landscape (HUL) in 2011. HUL stressed that heritage and development are potentially mutually supportive, fostering social cohesion and quality of urban living. HUL tool groups (community engagement, knowledge and planning, regulatory systems, and finance) are being broadly applied, and landscape architects can benefit from partnering to activate them effectively.

China's rubble streetscapes.

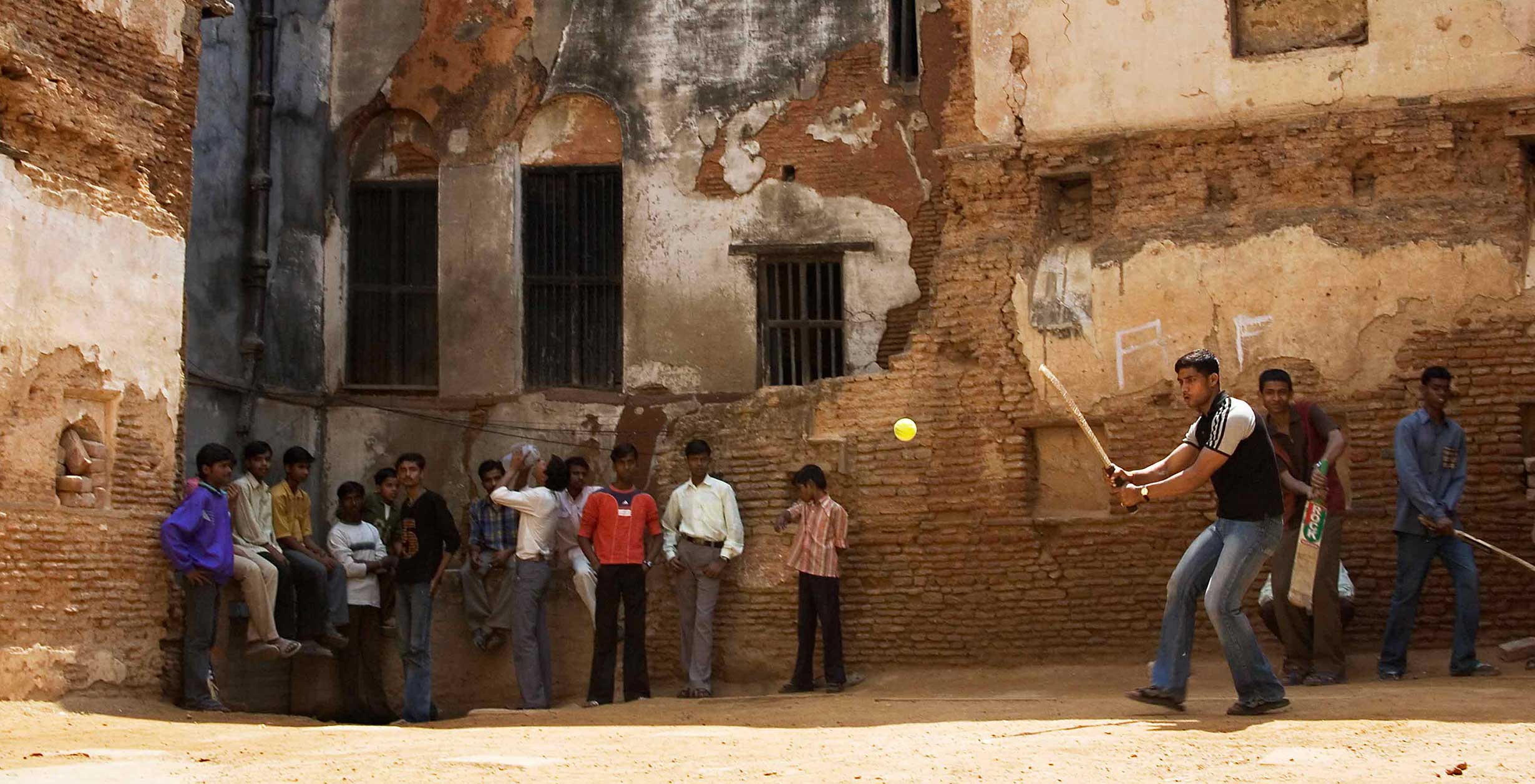

A street scene in Varanasi. Image: Jorge Royan

Rawalpindi Bazaar, Pakistan. Photo Trueblood786/Michelle Ahmad

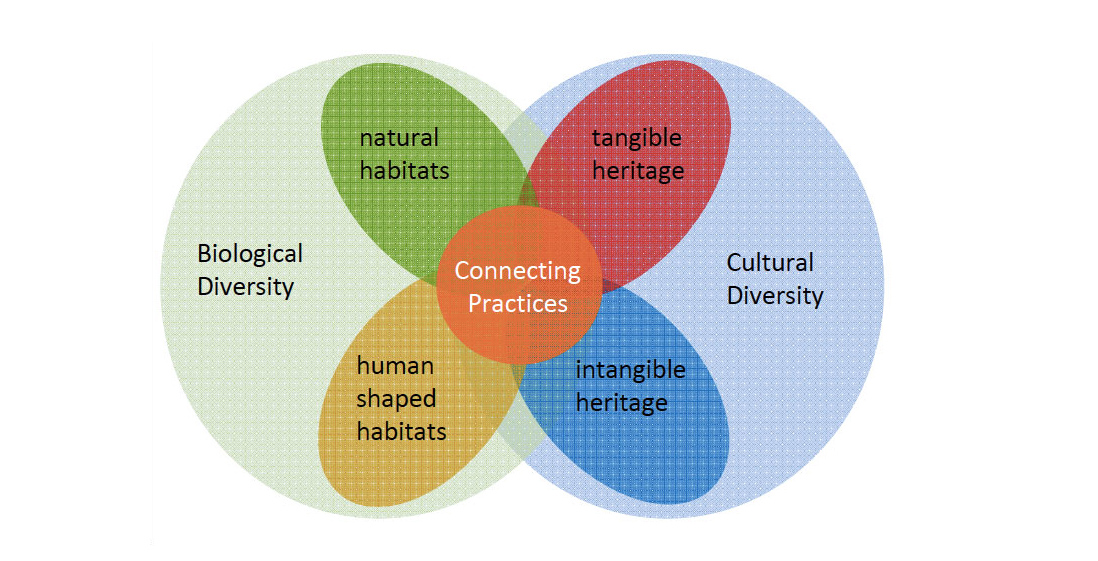

A parallel movement recognises intertwined culture and nature. Expressed in the 2015 International Union for the Conservation of Nature (ICUN)/International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) “Connecting Practices” initiative and a growing body of literature, we must acknowledge the inseparability of culture and nature to survive.

Humanity needs nature.

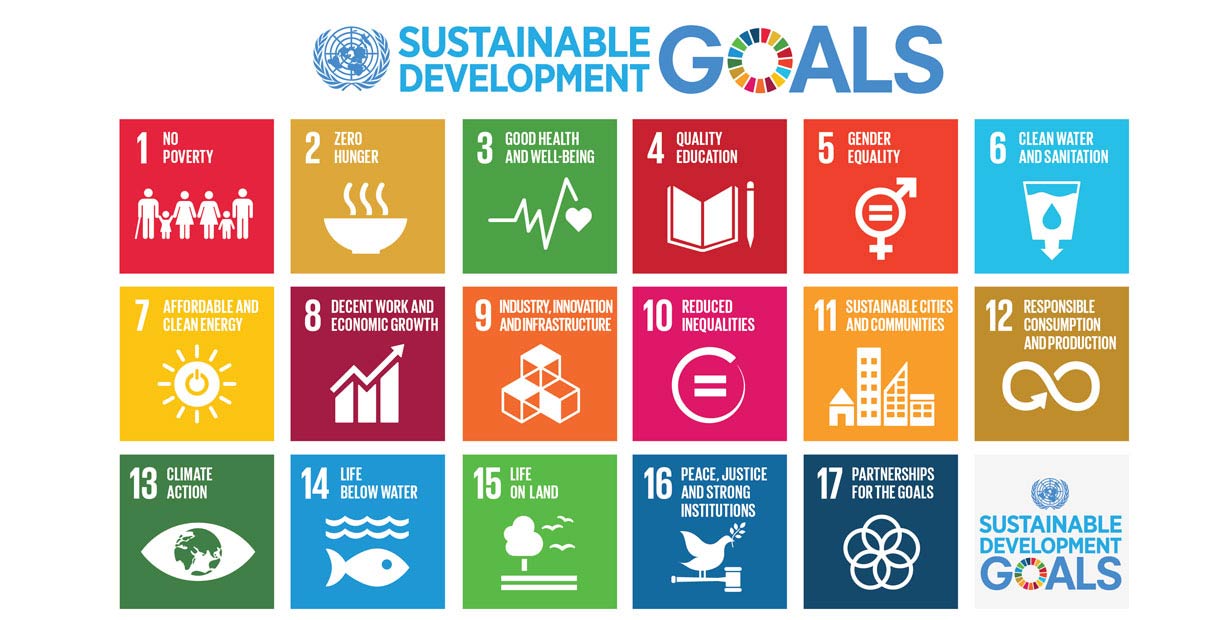

The millennium rumble has risen to a roar, with widespread opportunities to contribute. Embracing complex pervasive issues, the United Nations created, through an open two-year process, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs), adopted by 193 sovereign states on September 25, 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development lays out 17 goals with 169 targets to guide nations toward patterns of development that favours diverse life on Earth. This transformational agenda is impressive because “never before have world leaders pledged common action across such a broad and universal policy agenda.” In parallel, the climate change forum at COP 21 led to a promising global climate agreement.

Why should landscape architects engage in achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals?

Landscape architecture skills foster inclusive processes, partnering, and innovation that can rise to these massive challenges. The UN SDGs agreed worldwide framework, a complex global platform of goals and targets advances now. If landscape architects take this framework seriously, partnering to achieve the global 2030 Agenda, we can make meaningful contributions to the momentum toward a sustainable future.

An Indian HUL approach.

The UN's sustainable development goals.

The connections between natural and human heritage.

Which of the UN Sustainable Development Goals are relevant to landscape architects?

A landscape architect might focus initially on Goal 13: Climate Action, Goal 14: Life Below Water, and Goal 15: Life on Land, as all are relevant. Digging deeper, the goals and specific targets reveal a multitude of ways to contribute individually with clients, teams, civic leaders, community partners, and collectively through professional organisations, leadership and advocacy.

For example, Goal 1: No Poverty. The World Bank cites a veritable tidal wave of urban in-migration: 5 million people monthly seeking an elusive better life, outpacing sustainable growth, increasing poverty, disparity and inequality. Research and observation verify that few trees are found in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. What can we do? Plant trees in poorer areas to build community wealth and advance social justice.

Take Goal 2: Zero Hunger; a key benchmark as 800 million people go hungry every day. Targets address food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture with initiatives in urban agriculture, soil remediation and market spaces as contributions. Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being includes, “halve the number of global deaths and injuries for road traffic accidents.” Landscape architects design better intersections, complete streets and multi-modal corridors. For Goal 4: Quality Education, we can serve as informants and advocates for sustainability and resilience.

Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, addresses protecting water resources, counteracting pollution, and restoring water-related ecosystems. All things we do. Goal 7: Affordable Clean Energy focuses on renewable energy, where landscape architects can contribute to siting and impact assessment. Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth strategically seeks to “decouple economic growth from environmental degradation.” For example, employment could spring from public spaces as we adapt and shape them anew.

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities addresses housing, transportation, planning, safeguarding cultural and natural heritage, provision of public space and reducing disaster impact and environmental degradation. Target 11.7 seeks to “provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces,” engaging the urban commonwealth of public spaces. Accessible open spaces offer economic, environmental and social benefits as cultural assets today and a legacy to the unborn. We can uplift public spaces.

Goal 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions and Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals offer pivotal constructs for progress. Recall Jane Jacob’s words that “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.”

Landscape architects must collaborate in shaping policy, planning, building and setting new standards. The World Urban Campaign, Habitat III, and the 2030 Agenda await.

Join me there.

The New Landscape Declaration: A Summit on Landscape Architecture and the Future was organised by Landscape Architecture Foundation in June 2016 and was held at the University of Pennsylvania. To read more from the 26 papers presented click here.