In Australia, a sewage facility is now one of the world’s greatest bird habitats

Melbourne’s Western Treatment Plant treats 500 megalitres of wastewater a day. It also rivals Kakadu for diversity and abundance of bird life. What lessons might this constructed landscape offer for the management of the planet’s increasingly beleaguered ecosystems?

Our diesel four-wheel drive had flushed a flock of birds. From behind a small cluster of bushes, a seemingly endless flow streams skyward, as if from a magician’s hat. “Probably a few hundred birds there,” says John Barkla, my expert guide for this special morning expedition, as the now fully airborne flock moves across the sky, a cloud of grey backs and white bellies.

We are deep within what some call Melbourne’s Kakadu – the Western Treatment Plant, a 110 km² sewage facility 30 kilometres west of Melbourne’s central business district, on the coast of Port Phillip Bay. Barkla is one of Australia’s most passionate birders, president of Birdlife Australia and chairman of the Western Treatment Plant Biodiversity Conservation Advisory Committee. He has been visiting the Western Treatment Plant for almost 50 years, and I am quickly learning how to play the game of bird watching – the conventions, the goals and the delights. One convention is estimating the number of birds in each flock. Another is naming every bird at sight. It makes for fascinating, but fragmented conversation.

“This whole area would have always been valuable for birds; they would have been coming here for millennia… Look at these terns! Fantastic!… And when it was changed, fortunately it was changed in a way that’s accommodated the birds. What normally happens when man interferes is we do it in a way that destroys the natural value… A sea-eagle on that post… But in this case we have done it in a way that has maintained or enhanced the value.”

As we drive, our conversation moves from landscape management to the plight of global biodiversity. From hope to gloom, always accompanied by background birdwatching commentary. “Two black kites… yellow-billed spoonbill… many hundreds of birds in that flock… Red-necked stints over there…”

“It’s not unknown to see a dozen raptor species in a day here, which is really quite an extraordinary number,” Barkla remarks as we pass two swamp harriers feeding on a dead rabbit. One flies off with the rabbit leg in its talons. “We have done an extremely good job of draining wetlands in Australia. This here is a memory of what might have been all around Port Phillip Bay in the past.”

The constructed ecology of the Western Treatment Plant has recorded over 280 bird species. Image: Watkin McLennan

Birdlife abounds at the Western Treatment Plant ponds. Image: Watkin McLennan

View into the still waters of the Western Treatment Plant's constructed pond ecology. Photo: Watkin McLennan

Although the bird numbers in the Western Treatment Plant are immense, in many other parts of the country this is no longer the case. They say that before European settlement, Melbourne was home to wetlands, billabongs and creeks, all of which created a landscape of abundant life. For the most part, this abundance has been lost – drained first, paved over later, in a process of urbanisation that took less than 200 years. However, in Melbourne’s west, this wetland fertilised by 120 years of sewage, a landscape closely tied to the same urban expansion thrives.

The Western Treatment Plant receives 52% of Melbourne’s sewage, around 500 megalitres or 200 Olympic swimming pools a day. Comprised of sewage treatment lagoons, wetlands and paddocks, it is three times the size of the City of Melbourne and is accessed by three exits along the Princes Freeway. Its comparison to the more popularly renowned Northern Territory National Park, however, is warranted – a similar number of bird species have been recorded at the Western Treatment Plant to Kakadu, and it is listed under the Ramsar Convention on wetlands. Roughly a third of all Australian bird species have been sighted at the plant and birds flock here from as far away as the Arctic for its permanent and abundant supply of nutrient-rich water.

“Melbourne Water has done quite an outstanding job of maintaining this over the last 120 years. It’s not like other wetlands that have good years and bad years. At the Western Treatment Plant it’s always a good year,” Barkla says.

“People from around the world visit. They are always just amazed, absolutely amazed. We can travel around here for just one day and see 100 species of bird. There are not that many places in the world where you can do that. And it’s 40 minutes from a city of five million people. Staggering!”

It is an ecosystem powered by a city’s waste. At the plant, it is possible to see, smell and hear what happens when engineering, scale and ingenuity align with natural processes. However, behind the banks of swans, gulps of cormorants, rafts of ducks, convocations of eagles and pods of pelicans not everything is so magical. Today, the sewage treatment process can produce recycled water with fewer nutrients than before. The thriving wetland bird habitat is no longer a by-product of the treatment process by default. It is there because we protect it. It has become a part of Australia’s conservation estate and this brings challenges: identifying and meeting conservation objectives, and securing the resources to do so. However, due to the plant’s constructed nature, it is also a place where conservation can be innovative. We can challenge our image of nature – our role within it and the values we hold for it.

From sewage to award-winning agricultural produce

This concept was applied on an immense scale in Werribee. During Victoria’s Gold Rush in the 1850s, Melbourne was plumbed into what at the time was the world’s largest artificial reservoir. The Yan Yean reservoir supplied plentiful water to the young city, and with this abundant supply, waste abounded in the streets and creeks. “Marvelous Melbourne” became “Marvelous Smellbourne”. Cholera and typhoid were common. A Royal Commission into Melbourne’s sanitation took place in 1888 and led to the establishment of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works (MMBW). Its first task was to establish a sewerage system.

In the late 19th century, there were three ways to deal with sewage. The first was to release the sewage untreated into a large tidal body of water, much like Sydney’s solution. Port Phillip Bay didn’t offer the volume of water exchange required. The second technology was chemical treatment, followed by waterway release. This involved the use of lime and other chemicals to precipitate out the nutrients.

The third solution, the one chosen, was farming. Two treatment farms were suggested in the original design, one farm for the east and one for the west, in Mordialloc and Werribee respectively. At this early stage in Melbourne’s history, the east of the bay had already been established as a retreat for Melbourne’s elite, so Mordialloc was quickly disregarded. The Werribee site is within the traditional lands of the Wathaurung people. The land had been taken as a part of Batman’s Treaty and used for grazing sheep.

The Western Treatment Plant land was used for grazing sheep by settlers. Photo Martin Bisof

An icon of Australian avifauna: Black Swans still find a home at the Treatment Plant. Photo: John Barkla

The wider landscape of the Treatment Plant includes grasslands that support indigenous fauna. Photo: Germane Jaws

In the lead up to my guided four-wheel drive adventure through the Western Treatment Plant, I met with Melbourne Water’s Paul Balassone and William Steele in their Docklands office. Balassone manages cultural heritage for the organisation, while Steele is an in-house ecologist. As Steele explained, “Prior to settlement, the area had intertidal mudflats that would have been important for migratory shore birds, intertidal salt marsh that would have been important for orange-bellied parrots; it was probably pretty sparsely wooded with grasslands too. Lake Borrie was a natural wetland. It wasn’t like a Kakadu, but nonetheless an important wetland.”

The Werribee Farm was commissioned in 1897. Sewage was directed out of the city by gravity via a network of sewers to the Spotswood Pumping Station, now Scienceworks. From there, the sewage was pumped via rising mains to the Main Outfall Sewer, where the sewage was conveyed to the Werribee Farm. Small channels branched off the main sewer and passively led the sewage around the entire farm. For this, the farm was graded and divided into 400-metre by 200-metre paddocks. The paddocks were flooded with raw sewage on a 16-to-18-day cycle. This “humanure” was liquid gold and cattle and sheep grazed the resulting pastures. It was such a successful system that MMBW produced agricultural profits and award-winning cattle. For the first several decades, the farm existed as much to grow food as it did to process sewage.

There was another consequence of this treatment method. The paddocks had deep drainage channels that received the effluent once it had filtered through the soil. This nutrient-rich water was released into Port Phillip Bay with astonishing effect. The nutrients fertilised the mudflats and this became the foundation of a food web that, to this day, supports one of Australia’s biggest congregations of shore birds.

“It shows enormous foresight to have done this without the use of chemicals,” Barkla says. “Yes, it takes more land, but it is very gentle on the environment.”

I suggest that it actually seems to have been beneficial to the environment, and he agrees. “It’s creating wonderful habitat, supporting huge numbers of birds. You can see just how many over there,” he says, pointing to a bank of 50 swans. “Notice how they are congregating around the [effluent] outlet. There are multiple outlets that we have created because we noticed that where there are nutrients entering the bay, lots of birds congregate. So Melbourne Water created several small outlets.”

A pair of Pink-eared Ducks enjoy the food-rich waters of the western Treatment Plant. Photo: John Barkla

A large flock of Pink-eared Ducks. One of many visiting species that come in huge numbers. Photo: John Barkla

Red-necked Avocets gather at Werribee's Western Treatment Plant. Photo: John Barkla

But the initial soil filtration process was not perfect. During the winter, pastures grew more slowly and the soil became saturated. The bay often received under-treated effluent and smells drifted around the Werribee area. The problem was solved first by the use of grass filtration and then later by the development of treatment lagoons. The first lagoons were built in the 1930s and over the next 50 years, dozens more were built.

Today, lagoons are the defining feature of the landscape. Their different shapes and sizes tell a story of experimentation and innovation. The oldest lagoons are built where Lake Borrie’s wetlands once were, in organic shapes that follow the original topography. The mid-century lagoons were built on the grid where the increasingly redundant filtration paddocks were sited. Finally, the modern lagoons are deep and rectangular, each one matching the scale of an A380 runway, only here pelicans rather than planes put down their landing gear.

Mechanised sewerage system puts pressure on Werribee’s wetland ecosystem

Over time, the sewage treatment process gradually separated from farming. In 1992, the Werribee Farm became the Western Treatment Plant and in 2012, Melbourne Water leased the remaining farmland to a private contractor.

“In the old days, we were a farmer by default because it was a part of the sewerage process. But then as sewage treatment became more lagoon-based the requirement for agriculture was less direct. It was then seen as an unregulated income for a government-appointed organisation,” Steele says. “We talk of three core values: sewage treatment, agriculture and conservation, and how well they are integrated. However central management of the site has been lost to some extent. This means we must continually work to maintain synergy between these values.”

During the modern era, through a process of mechanisation, optimisation and siloisation, the synergy between sewage treatment and conservation has become less clear. Sewage treatment technology, once so closely tied to the landscape, has become increasingly isolated. It has moved away from passive landscape-based processes to more mechanical and controllable ones. The activated sludge plants, bubbling pools of sewage, do not serendipitously create bird habitat – this must now be created and maintained in its own right. This has created diverse responsibilities that Melbourne Water must now negotiate.

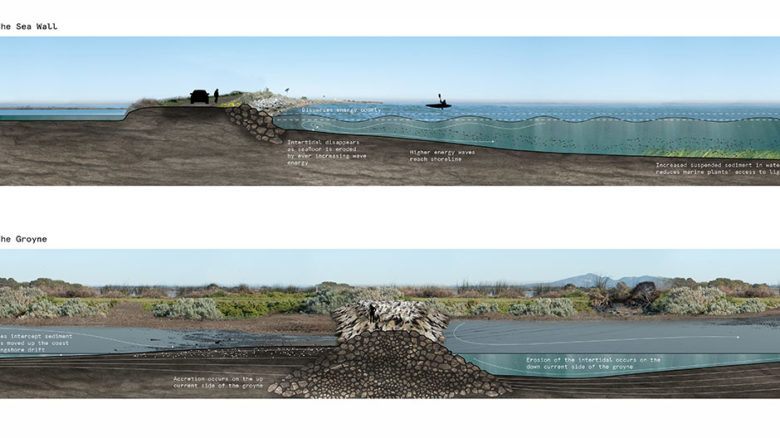

Section showing the interface of sea and intertidal ponds at the Western Treatment Plant. Image: Watkin McLennan

Section showing the complex water management and grading of the Western Treatment Plant. Image: Watkin McLennan

Section showing mounds designed for the critically endangered Orange-bellied Parrots. Image: Watkin McLennan

In the 1990s, Melbourne Water partly funded an award-winning study of the health of Port Phillip Bay. It determined that one third of all the nitrogen entering the bay came from the Western Treatment Plant, with another third coming from the Yarra River and the final third stemming from all the other waterways expelling into the bay combined. The study found that the bay was in good health and recommended reducing nutrient loads as a precautionary measure. Following this recommendation, Melbourne Water invested in treatment upgrades that both reduced nitrogen in effluent and also enabled the production of high quality recycled water for farms, parks and market gardens.

I ask Barkla what would happen if all the sewage was recycled in this way. “In a situation where the water was only being used for commercial purposes, like irrigation of market gardens for example, and there wasn’t any water left over for conservation, that would be a problem,” he says.

I put it to Steele that this seems to present a tension between Melbourne Water’s conservation and sewage treatment remits. In response, he reflects on the period of time around 2004 when they stopped treatment in several of the lagoons, including Lake Borrie.

“Borrie still received treated water because we are obligated [to provide it], but we stopped raw sewage. We were concerned for the health of the wetlands. We knew elevated nutrients were leading to a major food resource, so there was a chance there would be an impact.” Steele says. “We realised we could reduce nutrient loading to some extent without adversely affecting water bird habitat. But we didn’t know what the threshold point would be, when nutrient loading might become too low. This meant we needed close monitoring of water bird numbers. We developed a strategic management plan to guide our response. Part of this plan included trigger points and a plan for what we would do if we hit those trigger points.”

However, Steele was unsure as to how robust the trigger points were. They involved counting the number of birds over time and performing a trend analysis. “Biological values are tremendously variable,” he tells me. “With the waterfowl, we can have up to 70% of Victoria’s count sitting there during drought, huge numbers, 200,000 of them. If it rains up in Queensland they will almost all get up and move.”

Trigger points were hit but he was not confident that a lack of nutrients was to blame. Then there was a breakthrough. Andrew Hamilton, a PhD student at the time, was monitoring the “activity budgets” of birds. Rather than simply counting birds, he recorded the proportion of time that each bird was feeding, sleeping or grooming. “The proportion of birds on Lake Borrie actively feeding was dropping. And that was a signal to me that we had pulled the nutrients back too far,” Steele says.

Fortunately, because of the sharp increase in Melbourne’s population over the past decade, the re-introduction of sewage to Lake Borrie could be justified. “I wasn’t at the point of saying that we really need it (sewage), but it was at a point where I thought it would be a pretty good idea,” recalls Steele. “I could not have argued the high cost from an ecological point of view, but since reintroducing sewage to Lake Borrie, there has been a huge bounce back.”

The story demonstrates the complexity of what Melbourne Water must now manage. Sewage treatment is easy by comparison to ecosystems – managing the interests of both is harder still. There is an inherent paradox to biological conservation: how do you conserve a chaotic, complex system, one that requires change to thrive? Australia faces this challenge across its entire conservation estate – land put aside to be protected from modernity. Management objectives often revolve around maintaining stability or returning to an imagined pre-colonial condition. But in an era of rapid climate change, introduced species and European landscape management practices, are these realistic objectives?

The Western Treatment Plant: a thriving landscape for the Anthropocene

The Western Treatment Plant offers an opportunity to challenge the norms around biological conservation in Australia. It is a constructed landscape, the product of modernity. A landscape that presents a positive vision for the Anthropocene. It is utterly modified from its pre-colonial state, but we do not need to return it to what it once was, nor put it in a resource-intensive static limbo. Its engineered nature gives us the freedom and flexibility to experiment – to garden.

There are glimpses of Melbourne Water doing this already. Sea level rise is a present threat to the plant. Since 1897, the sea level in Port Phillip Bay has risen by 20 centimetres. Barkla tells me that, over the 50 years he has been visiting, the coastline has always changed. “It used to be a little bit of take here and a little give over there. But for the past 20 years it has just been take, take, take.”

By 2100, if nothing is done, estimates place 10-15% of the plant under water. The modern industrial lagoons are not under threat, but many of the conservation lagoons and intertidal zones are. “We are losing shoreline and coastal habitat,” Barkla says. “As it continues, it will start to undercut the road, which will lead to the need for reinforcements, walls, that have their own problems. So potentially the answer becomes cutting the road and letting the water in.”

Melbourne Water has started doing just that at a site tucked away in the plant’s west, which Barkla takes me to in the four wheel drive. As we drive down along the coast, I see traces of an old road, which had previously separated the bay from lagoons. Now they are part of the intertidal zone. Big slices have been removed from the old road, creating a chain of “barrier islands” and transforming effluent ponds to intertidal salt marsh. This phased project is still in progress. The first lagoon I see was cut in 2016; in the barren white mud you can still see the bulldozer tracks. The next lagoon, cut in 2010, is full of brown, red and grey salt marsh vegetation. Sandpipers wade in small ponds. The vegetation hides “several species of skulking crakes and rails”, Barkla assures me.

An Australian Spotted Crake at the water's edge. Western Treatment Plant, Werribee. Photo: John Barkla

More than water birds inhabit the Western Treatment Plant. Stubble Quail. Photo: John Barkla

A Buff-banded Rail at the water's edge at Werribee's Western Treatment Plant. Photo: John Barkla

“It was a bit experimental for Melbourne Water,” Steele says of the project. The process involved removal of sewage sludge followed by cutting and removing the bund, the lagoon wall that supported the road and separated the lagoon from the bay. “It worked better than we thought. We didn’t have to do weed control. We didn’t have to do re-veg. It [salt marsh] just came back by itself. We actually won a River Basin Management Award.”

Due to the challenges of funding conservation works, the second lagoon, the one still barren, had a tighter budget. Steele tells me that in an effort to manage the budget, they made smaller cuts in the bunds. This reduced the amount of earth that needed to be moved, but it also limited the tidal influence. However, despite mixed success, Steele was positive. “The bigger picture here is a response to sea level rise. So we are using that as an example to show that we can adapt, because some see building a sea wall as the most effective means to protect coastal assets.”

Melbourne Water is currently working on a foreshore management plan. As Steele explains, the plan doesn’t use the word ‘retreat’ but ‘adapt’. “The Western Treatment Plant is one of the only places on the bay where the coast can adapt, because around most of the bay you have houses or railway lines close to the shoreline. If you build seawalls at the WTP, you will lose the intertidal mudflats. We need to have that nice shallow gradient all the way inland to let the salt marsh migrate.”

As Balassone concludes, “We are trying to get engineers to think like environmentalists and environmentalists to think like engineers to drive integration of management practices. When you look at the business of water, drainage, sewage – those hardcore services – and look at what we’re dealing with – a Ramsar wetland – we constantly have to engage internally, let alone externally. We can say the 19th of May 1892 was the turning of the sod. But there’s never been a completion date. We are ever evolving.”

Pied Stilts enjoy the lagoons at Werribee’s Western Treatment Plant. Photo: John Barkla

What kind of landscape do we want? The romantic vision of nature depicted in the 18th and 19th centuries remains a potent cultural force. Instagram is full of epic mountains, remote beaches and wild rivers, the humanness of these landscapes conveniently cropped out of view. At the Western Treatment Plant it is impossible to crop out the human hand: the geometric rhythm of the lagoons and linearity of the roads, a patchwork of habitat quadrats each uniquely managed – some optimised for frogs, others for ducks or ibis. Here, the question of what we want is important. Because, what we have is no longer there by natural default, nor required to process our waste, but there by choice.

I asked Barkla to compare the Western Treatment Plant to other birdwatching sites around the world and he stumbled. “Ahh…the Pantanal…maybe that compares…Antarctica too. It’s a very, very incredible place here for bird watching. I think this is better than Kakadu.”

What we have is marvellous, and at risk of inundation.

–

Watkin McLennan is a Melbourne-based landscape architect who recently completed his masters of landscape architecture thesis at the University of Melbourne. The thesis explored the intertidal landscape of the Western Treatment Plant in the context of sea level rise and the proposed Bay West container port.