How to design with nature now?

A new book marking fifty years since the publication of Ian McHarg’s influential Design With Nature reflects on his work, finding enduring lessons for tackling today’s many environmental crises. The following excerpt is written by Andrew Revkin and serves as the foreword of Design with Nature Now.

[This article is an extract from Design with Nature Now edited by Frederick Steiner, Richard Weller, Karen M’Closkey and Billy Fleming, and published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, in association with the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design and The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology. It is available for purchase here.]

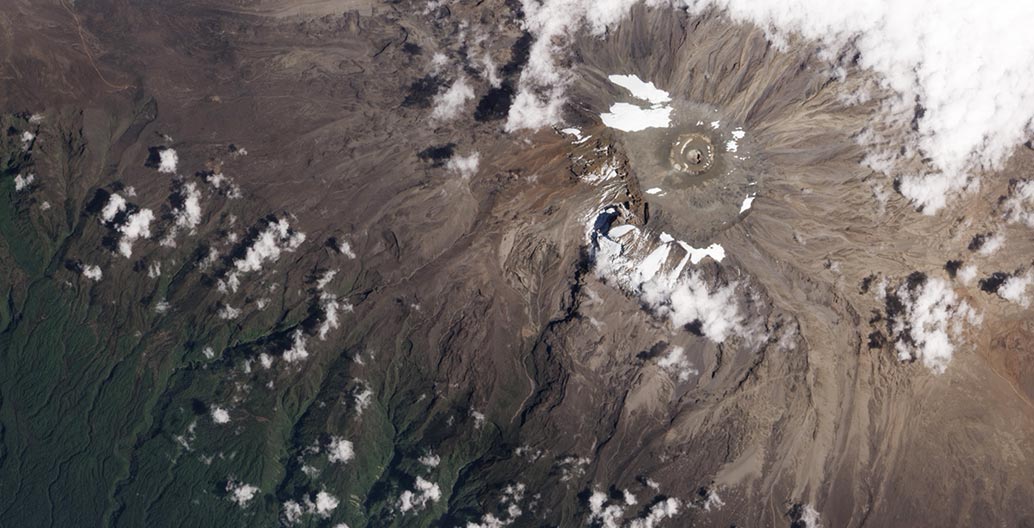

In early March 2001, amid the intensifying flow of news at the heart of my beat covering the environment for the New York Times, word arrived that Ian L McHarg had died. When I was asked to step away from the news grindstone to write his obituary, I considered it an honour. It was also a bit of a relief to tackle a more uplifting topic for a day or two. I’d just had a front-page story on the “message in eroding ice,” as Mount Kilimanjaro’s fabled white cap shrank under the effects of climate change. I was tracking conflicting signals out of Washington as lobbyists and environmentalists fought to reverse or defend George W. Bush’s campaign pledge to regulate heat-trapping emissions from power plants. (Industry won the tussle later that month.)

What better tonic for those dark days than to explore such a pioneering and productive life? Until then, I had no more than a superficial awareness of McHarg from courses in college. As I dug into our clip file and data bases and began phoning his peers and pupils, it quickly became evident that while Design with Nature was revolutionary in its call for conforming to, rather than competing with, ecology, this landmark book was just one of McHarg’s legacies.

The resulting obituary focused on McHarg’s achievements and innovations, such as his famous ‘layer cake’ of transparent site maps, designed to help clients or communities weigh the value of any human development against the functions of underlying soils, water flows, and other environmental conditions. But I am glad at least one line conveyed what felt like McHarg’s other enduring gift: “His greatest legacy was not his method, or even his seminal book; it was his passion for respecting the living land and his volcanic determination to brand successive generations of planners and landscape architects with the same ethic.”

In Design with Nature Now, an array of McHarg’s contemporaries—along with practitioners, scientists, and scholars in fields from planning to ecology to comparative literature—explain why there has never been a greater need for McHarg’s way. That might seem a tough case to argue given the pace of change in both the Earth system and human systems as the third millennium speeds along. What is the role of design in a world where sea level, climate, invasive species, surging cities, and technologies are all changing simultaneously? How does one define nature in the Anthropocene—a moment on Earth in which humans are jolting ecosystems and climate as powerfully as an asteroid strike has done in the past? And of course we are simultaneously poised to redefine nature at the genetic level as tools like gene drive technology offer the prospect—for better and for worse—of not just shaping some crops’ genetic traits but pruning the tree of life of inconvenient species like a disease-toting mosquito.

Actually, it is precisely that fast-forward state of the planet, and of Homo sapiens, that makes McHarg’s methods and motivation more vital than ever—and gives them influence far beyond the fields of landscape architecture and planning. Consider his eagerness to incorporate any discipline necessary to clarify an answer. Following the success of Design with Nature, McHarg strove to expand his design models from geology and ecology to include the human element, with the plasticity of culture introducing so many new variables. “How could we extend this model to include people?” McHarg wrote. Along that path, McHarg added anthropologists and ethnographers to his circle. There is still much to learn from this aspect of his work, given how, all these decades later, many academic, governmental, and corporate structures and norms—and journalistic norms, for that matter—still impede interdisciplinary collaboration.

There are also lessons to glean by examining how McHarg shaped his presentations. He tended to use them less to make his case for an environmentally sound design than to enable stakeholders to find their own logic in sensible choices. To absorb this, it is best to see him in action—something not possible in this book. But fortunately he is on dynamic display in the remarkable 1969 public television documentary Multiply and Subdue the Earth, which includes McHarg’s 1968 presentation to the Metropolitan Council of Minneapolis–St. Paul and surrounding counties, in which he makes the case for resilient, ecologically attuned planning.

“I have spent years of my life offering my palpitating heart to various people who couldn’t care less,” he says, pacing in front of the panel of planners and other local figures. “So palpitating heartism doesn’t really get you anywhere at all. It seems to me that one really needs to have two things. You not only need to be able to say, ‘Don’t.’ You also want to be able to say, ‘Do.’” He calls this two-pronged approach a “positive inducement process.”

An accumulating body of behavioural and social science has validated this approach for dealing with a divisive issue like global warming and the local and planet-scale design debates it has sparked. As Dan Kahan of Yale Law School has demonstrated in empirical studies, more information, with or without great graphics, can deepen, rather than dispel, divisions. He calls the phenomenon “cultural cognition.” But that same body of work shows how a conversation, like a landscape, can be designed—in this case with human nature in mind. The result can be consensus on resilient and sustainable paths even amid divergence.

In several essays, contributors to this book note another factor that is critical to the success of a McHargian strategy for this century. That factor is not better data visualizations or better dialogue among experts and officials. It is representation: who gets heard at the table where decisions are made about roads and reservoirs, parks and pavement, or environmental laws and agreements. The success of a climate agreement, or a city, will depend on inclusion.

But the most resonant facet of McHarg’s method in the context of this century’s challenges is his focus on designing for the properties of a landscape or system. With biology, particularly evolution, as his constant touchstone, he aimed for ‘dynamic equilibrium’ more than a static, durable end point. That approach is invaluable given the complexity and enduring uncertainty in confronting human-driven climate change and related challenges. It would be easier to design a safe coastal city in a world with either a stable sea level or a known rate at which seas will rise. Neither is the case now, and will not be for decades, if not centuries, to come, according to a host of recent studies.

The same design philosophy is emerging in very different realms. Through the first quarter-century of international treaty negotiations aimed at avoiding dangerous global warming, the goal of most countries was a binding, robust, contract-style treaty that would govern the actions of signatories. In the 2015 Paris Agreement, negotiators finally forged an outcome that is itself a process—with norms for reporting nationally determined steps toward a safer human relationship with climate. At its core, that agreement is an iterative tool for ‘positive inducement’ that McHarg would have appreciated.

We need an expansion of McHarg’s methods, as suggested in the pages that follow, creatively reimagined to accommodate more complexity and diversity and to design—as much as that is possible— a planetary future with both nature, and human nature, in mind.

–

Andrew Revkin is the Director of the Initiative on Communication Innovation and Impact at the Earth Institute at Columbia University. Revkin has worked as a journalist and author covering sustainability for over 30 years, almost half of which was spent as a reporter for the New York Times. He has written three books on climate change.

Design with Nature Now was edited by Frederick Steiner, Richard Weller, Karen M’Closkey and Billy Fleming, and published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, in association with the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design and The Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology It is available for purchase HERE.