Design for the Anthropocene: the big-picture landscapes of Dirk Sijmons

Our landscapes will need creative, big-picture change to survive the 21st century. In this interview with Foreground, Dutch landscape architect Dirk Sijmons explains the uniquely influential background of his practice in public landscape works of the Dutch government.

This article is part of Foreground’s 2 Degrees themed series of essays

Foreground: You have led strategic and large-scale projects that influence government decision-making. This is not so common for landscape architects or designers. How did you come to be doing such work?

Dirk Sijmons: It is the background, the DNA of our office. We were all civil servants interested in the public side of our profession. We were involved in some of the largest projects that have ever been undertaken in the Netherlands. These were land use planning works that started just after WWII to modernise Dutch agriculture. It was a policy after the war, to regain our economic strength, and there was also the motive of avoiding future famine. The war ended with a terrible famine in the north of the country. But the project also proved to be an instrument to keep wages low, because if you offer cheap food, you can pay people less. So it was an instrument of economic policy. But then it was the means for the spectacular economic export success of Dutch agriculture. When I worked at the ministry in 1981, the Australian minister for agriculture visited the Netherlands and the speech writers of our minister did a good job by saying ‘I’m glad to shake hands with another agricultural superpower’ because they calculated that our stamp-sized country exported more than the whole continent of Australia, both in terms of dollars and biomass. It still does.

The work was also part of a cultural policy. The landscape would change and scale-up and modernise, but the aim was also to make attractive landscapes. The State Forestry Commission where I worked was by far the largest employer of landscape architects at that time. In the heyday of the land re-allotment and land use planning projects at the end of the seventies there were 250 thousand hectares in the process of transformation. So it was a very, very large project.

"So the natural expression of agriculture in the early days was extremely nice with meadow birds and rich biodiversity." – Dirk Sijmons

"Now that agriculture has become more and more viral, the biodiversity in our cities is higher than agricultural landscapes!" – Dirk Sijmons

Transitional patchwork agricultural landscape of Flevopolder.

Foreground: Thinking of the success that the Dutch government had, and your own success working there, why did you feel the need to set up a private practice? What would you do there that you couldn’t do in government?

Dirk Sijmons: Well, the whole program of the land re-allotments didn’t come to a crashing halt, but it was fading out slowly. And let’s say too that there was a neoliberalist wave in Dutch politics that considered these kinds of practices should be privatised. So we recognised these signals early and decided to start our own firm. While working in government, our brief was to devise plans to modernise the Dutch landscape within the existing landscape structure, but it became clear that this was impossible given the speed of agricultural growth. So we thought up the ‘Casco-concept’ that was about separating different forms of land use with different development speeds.

In the framework of the concept, we said we want to have the forms of use with very slow development speeds like forestry, drinking water supply, nature, etcetera, and then make this framework very robust. Then give, let’s say, a flexible work space for agriculture in the middle of that. We felt that if we went on with the old defensive structure, we would end up in a bad place. We tested that out in a competition in the Netherlands – a competition that we won! – about the future of our river landscape.

We made a ‘toolbox’ plan – a toolbox of tricks – where we showed this approach could work in a river area and boost both the ecology of the region and the economy of the region. Much to our surprise, some non-governmental players took up the toolbox, and the plan in a way self-executed in the decades after that. It led to spectacular nature development around our river areas. That was also the tail-wind for us starting our own office, and partly why we are not, shall we say, mainstream landscape architects. Basically, it had started with us trying to insert design into regional planning. We tried to broaden the field of landscape architecture.

Even in the State Forestry Commission we were often extremely frustrated. We weren’t allowed to touch the plans for the new roads, the plans for where the new farms would go, and most important the water plans. We were actually only allowed to do the planting plans – what the Americans call broccoli around the steak – you say parsley around the pig. Our work entered into new fields – it’s not new anymore – through doing research by design or practice. It’s one of our most interesting tools because we are able to address problems that may never get a paying client. By showing what the landscape could look like – by actually showing what landscape architects could add – you lay the first stepping stones that lead to paid commissions, even if in the far future! So this research by design made up almost half the portfolio of our office in the first five to 10 years.

Foreground: Are your partners also landscape architects, or do they have backgrounds in hydrology or agriculture or sciences or skills that wouldn’t be thought mainstream to landscape architecture?

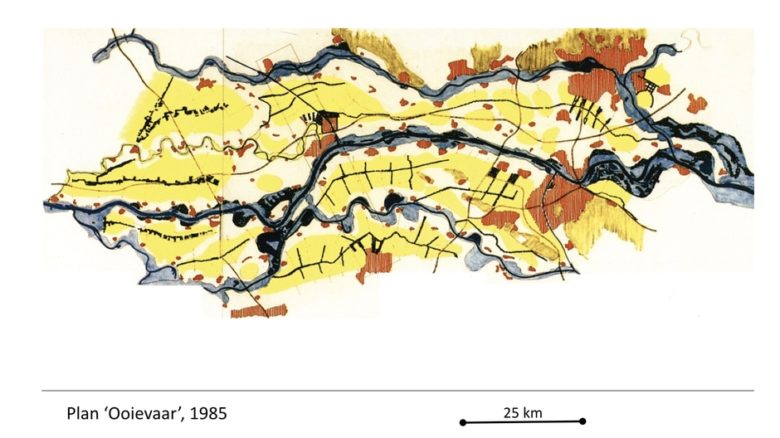

Dirk Sijmons: The three founders of the firm – Dick Hamhuis, Lodewijk van Nieuwenhuijze and myself – were landscape architects. And I am trained as an architect. But in a way, I am a child of the sixties and made my own study in Delft. I called it environmental planning. My first job was at the nature conservancy department of the ministry. And later I joined the State Forestry Commission and met my two other colleagues. But for instance Plan Ooievaar we did with an ecologist, a green art historian and a river hydrologist. Our work is always interdisciplinary but the office is strictly mono-disciplinary. Because we think that if we hire an ecologist – we are not a very large office – it would tie our hands to the specific opinions of the ecologist that we hire and we couldn’t work with the opinions of other ecologists. We had the ambition to form an interdisciplinary team for every project, fine-tuned for that commission.

Plan Ooievaar (Plan Stork) showing separation of land use types: blue/green framework of low-dynamic uses along the river and flexible high-dynamic spaces inland in yellow. Image: H+N+S

Plan Ooievaar (Plan Stork) on the River Waal.

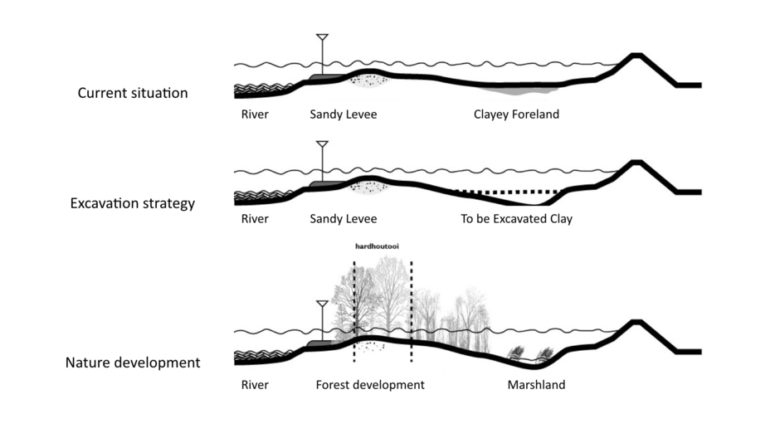

Plan Ooievaar (Plan Stork) sections showing strategic works. Image H+N+S

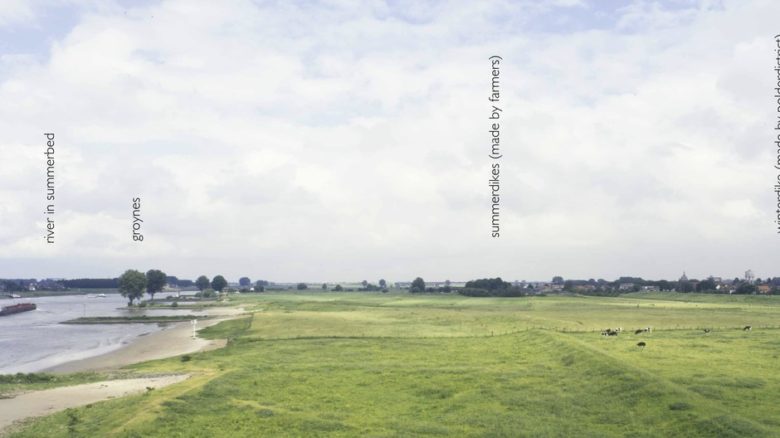

Plan Ooievaar (Plan Stork) strategic view of River Waal landscape.

Foreground: I expect Australians do not think of the Netherlands as having rivers, as much as canals, or of having once-wild landscapes that can be rewilded, as much as trying to encourage a diverse ecology where there was perhaps nothing but water before.

Dirk Sijmons: Indeed the large new polders played an exceptional role. We were brought up with the idea of nature in Holland is a sort of nice by-product of agriculture. So the natural expression of agriculture in the early days was extremely nice with meadow birds and rich biodiversity. Now that agriculture has become more and more viral, the biodiversity in our cities is higher than agricultural landscapes! In the early days when I worked at the Conservancy, every year we had to tell sad stories to our partners that this or that species has become endangered, this kind of butterfly has disappeared – very sad stories every year. But in the new polders something very exciting happened. Between the new towns of Almere and Lelystad, on a polder called Flevopolder, there was a reservation made for an industrial estate to be developed thirty years later and they didn’t drain that part of the polder because they didn’t need it yet. And what happened was that nature, as a sort of squatter, moved in.

It was a 6000 hectare reserve – the Oostvaardersplassen. Everybody was flabbergasted because all kinds of birds that hadn’t been breeding in the Netherlands since the mid-nineteenth century returned in their thousands. So everybody thought, look what can happen if we just give it the right conditions! It was very inspirational, both in landscape planning and in nature conservancy, that you could – it sounded a bit heretical – but you could develop nature. Inspired by the Oostvaardersplassen in the late seventies, a lot of new initiatives were taken.

This was actually the inspiration for our toolbox plan for the rivers. In our team we had the main, let’s say, discoverer of the Oostvaardersplassen the ecologist Frans Vera, who also was inspired to introduce year round grazing on the Oostvaardersplassen, choosing horses and cattle that could be there all year and build up the wild herds of horses and cows. It’s become a very difficult discussion in the Netherlands. Because of recent warm winters the herds have been growing and growing. The philosophy was that the herds would regulate themselves, which is a euphemism for letting the weak die over winter. For the farmers and others in the Netherlands this was too much to take and large-scale protests broke out. The first time that there were such large demonstrations around a nature reserve. People were throwing haystacks over the fences to save the animals and the discussion is not over yet.

![The Oostvaardersplassen. "[A]ll kinds of birds that hadn’t been breeding in the Netherlands since the mid nineteenth century returned in their thousands" – Dirk Sijmons Photo: Jac Janssen](https://www.foreground.com.au/app/uploads/2019/06/Sijmons-Oostvaardersplassen-JacJanssen-780x438.jpg)

The Oostvaardersplassen. "[A]ll kinds of birds that hadn’t been breeding in the Netherlands since the mid nineteenth century returned in their thousands" – Dirk Sijmons Photo: Jac Janssen

Konik ponies were returned to the Oostvaardersplassen as part of a native rewilding experiment. Photo: Steven Lek

The rewilded Oostvaardersplassen is a big tourist attraction in the Netherlands.

Foreground: There are aspects to this that are similar to Australia’s concerns with starving brumbies in the High Country – although they are certainly not native species. But there is an emotive history and heritage involved, mixed with considering endemic and threatened species. Are these ecological complexities linked to your affiliation with environmental organisation Natuurpro?

Dirk Sijmons: Yes, Naturpro is a network organisation with some commercial parties and some NGOs like the National Butterfly Foundation and others that all have a consensus that the use of indigenous plants is very important to keep our insect populations, for example, more vital. I’m not sure if it is the same in Australia, but the kind of pesticides in use in agriculture – I think it is a group called Neo-nics – is really a disaster for the insect population. So we have to make safe havens for these types of organisms. That’s where Natuurpro comes in. But that’s only one of our affiliations. We were one of the founders of the Foundation for Nature Development, a sort of discussion group of landscape architects and ecologists that we host that is interested in nature development in the Netherlands. The discussions range from the role of river and coastal dynamics on development to rewilding initiatives. In a strange way, if we could make a ‘new valley’ and follow Patrick Geddes a century later, we would see that agriculture near the cities is very intensive.

There are also places in Europe and America where agriculture can’t keep up with competitors in more optimal places. In parts of Europe, for the third time since the birth of Christ, agriculture is retreating – in the mountains, for instance, and old cultivated regions of the Apennines in Italy. They are being abandoned. Parts of Hungary, Eastern Germany and Russia. That is why we are seeing the return of bears and wolves and other large predators. And i think that is a very positive process.

H+N+S Landschapsarchitecten / Plan Ooievaar: een nieuwe kijk op het rivierengebied from Dutch School of LA on Vimeo.

Foreground: Do you have state advisors in architecture?

Dirk Sijmons: Yes, which is why the state advisor in landscape came about. We have a tradition of government architects which is over 250 years old, but in the 1980s a new element of cultural policy emerged and that was about quality of architecture which was a great success. And our office added argument to the relevance of landscape architecture to that field of cultural policy. The larger scale was introduced and the state architect at that time said I can’t do all this alone any more. I need someone for landscape, I need someone to help with large infrastructure, and I need a third person for heritage. So we were the four advisors to government. This also opened the windows of opportunity for bigger thinking.

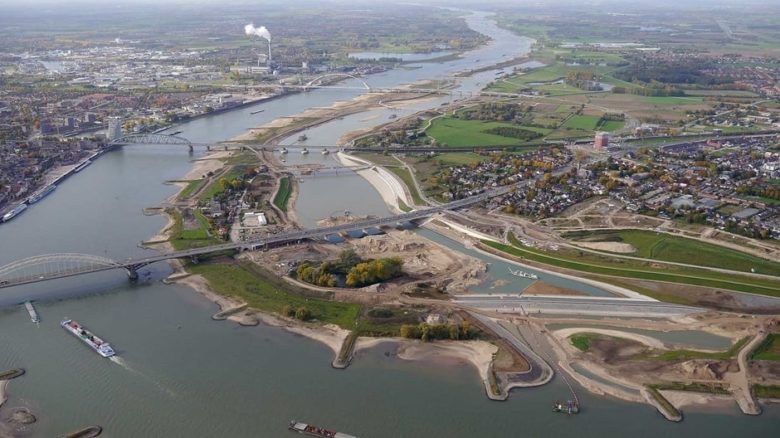

In March 2006 the project Room for the River program containing 32 projects, a 2.6 billion Euro budget, to say let’s not only care about safety, let’s also care about landscape, let’s make spatial quality the second goal of this enormous operation – like we did in the land re-allotment plans. I’m sure it’s the same in Australia when you utter the word ‘quality’ that every other partner at the table worries that it is going to be much more expensive. Of course we have to be sober and spend our taxpayers’ money as well as we can. But, in a strange, counter-intuitive way, looking at quality in a structural way, proved to make the project cheaper in the end.

The Waal river at Nijmegen was the site of the most complex Room for the River project, moving the dike at Lent 350 metres inland.

A Room for the River project. 'After' image of Waal river at Nijmegen. Photo: Johan Roerink

A Room for the River project. 'Before' image of Waal river at Nijmegen at high water.

Foreground: This is interesting for us. Various parts of Australia have tried to align what we do with, for example, CABE in the UK when looking to pursue quality with government. But it is confusing for people to know what the metrics are around the achievements of ‘quality’.

Dirk Sijmons: Indeed we live in a time where Excel sheets rule! If you can’t get something into an Excel sheet it doesn’t exist.

Foreground: More recently, you have moved from looking at nature and ecology to energy. Why is this important?

Dirk Sijmons: We are very interested in anything that is going to be a force for change in the landscape. The first point on my agenda when I became the state advisor for landscape was wind turbines. We have a flat horizon and everything that sticks up you can bet on having a very heavy discussion about. I read that in Australia you have wind turbine syndrome. We don’t have wind turbine syndrome, but we have wind turbine allergy. People are really very emotional about having turbines in their view.

Foreground: It is partly a heritage issue for us. It that the same for you?

Dirk Sijmons: Yes, it’s the same in Holland. One piece of advice I offered involved a process where I worked with philosopher, Martijntje Smits who did her PhD on the ‘domestication of monsters’, the introduction of plastics in western society. Plastics were the first man-made material and there was a sort of utopian euphoria about plastics. Then after a couple of decades people began to notice that this stuff doesn’t decompose and the dystopian side of plastics was revealed. And she had this theory that I thought was very useful for our discussion of wind turbines. She looked at different cultures around the world and how they had devised strategies to deal with the introduction of ‘monsters’. She devised a typology of how a culture makes a strategy to meet a new challenge. Without going into the typology, I commissioned four landscape architects and one artist to fill in the roles of this typology and see how it could stimulate ideas and discussion.

I was fascinated by energy and energy transition which is, of course, one of the few ways to mitigate climate change. I think that it is not only a fear of what happens to our horizon line, but there are deeper fears involved here. We were convinced that the fear of wind turbines is because they are monuments for the new time. And in the new time you will not be sure you can keep your privileges. You don’t know what you will get after the transition that is needed. In a strange way, I think right wing populist movements in Europe and the US have one thing in common – they are all denialist. They can’t believe that climate change is human-induced because this will topple their whole world view.

The Dutch energy landscape is changing with ongoing innovation. Goliath Poldermolen and new windmills. Photo: Uberprutser

A speculative windfarm of 25,000 turbines provides 90% of energy needs to North Sea countries. From the animation by H+N+S Landschapsarchitecten

Current North Sea windfarm.

Foreground: You will find this conversation very lively in Australia with our recent election.

Dirk Sijmons: Yes indeed! For designers, I think the essence is that when we want to substitute renewables for fossils, we will have to harvest ‘thin energy’. And harvesting this energy will require large surfaces and infrastructure. It will be visible everywhere and high visibility is what causes these NIMBY reactions. In the Netherlands, every discussion about wind turbines – and lately also solar fields but that’s another story – ends in people suggesting we put these things on the North Sea. Not in my backyard. And so I took up that challenge for the biennale of 2016 together with the curator Maarten Hajer and we made an animation. We showed that if we were really serious about this transition we could – with some ambition and some, let’s say, Chinese building speeds – put 25 thousand wind turbines of the largest model and provide 90% of the North Sea countries energy needs. So we used the NIMBY reaction to show want can be done!

It’s not only about energy, it’s the land use you have to consider in climate policy. And for coastal areas, the adaptation to sea level rise is an urgent matter. I think we will be in for this conundrum of wicked problems for the next century. We are living in the Anthropocene of Paul Crutzen and that has far-reaching implications. I think it is also important for our profession to let that sink in. I’m very glad I will be meeting with Clive Hamilton. I’m going to Canberra and he told me it’s ‘only’ a three and a half hour drive. You have to plan it carefully if you do that trip in our country! I wrote an article about navigating the Anthropocene. I want to discuss it with him. He doesn’t fly any more.

Foreground: What advice do you have for those entering the landscape architecture discipline? How important will it be to rethink our education?

Dirk Sijmons: It is very important to look at our education and position the next generation of students in this changing world. But also inform them very openly about what we can and what we can’t do as landscape architects, or any other particular job. Because I think sometimes we are overreaching. We position landscape architects as saviours of the world and I think that is a view we need to discuss right now. You also see it now because of the 50 year anniversary of Ian McHarg’s Design With Nature. There’s also this discussion in the United States: are we over-reaching?

I did a lecture at the World Design Summit in Montreal a couple of years ago and the University of Massachusetts. The lecture was called ‘Turning problems into parks’. That’s indeed what we do. You give us a problem and you get parks as an answer. We make public space. That’s a very important role – it’s our social role – and we have to be very good at it. But it’s not going to solve global problems. In the same way, music is not being composed to solve our noise pollution problems. So there are different points where our field can have influence. Research by design could be one of the things that our students have to learn, and learn to play a more activist role too. But I think we have to be clear that these are three roles that have things in common but are different: the delivery of well-designed public spaces, research and design visualisation, and activism. We should not mix them up or you can end up in a completely non-productive situation.

How the profession positions itself and how the student positions themselves within their profession is of paramount importance in every curriculum. They have to be ready for new situations. They are entering situations created by the Anthropocene and there is a perfect storm brewing. I don’t have answers for the Anthropocene I’m afraid, but it will offer completely different opportunities for work in the future.

–

Dirk Sijmons is a founder of H+N+S landscape-architects, Netherlands and the recipient of numerous awards including the Prince Bernard Culture award for regional plans and research and the Edgar Doncker prize for his contribution to ‘Dutch Culture’. Sijmons was appointed as the first State Landscape Architect of The Netherlands (2004–2008) and is Chair of Landscape Architecture at TU-Delft University. He has worked for several government ministries and the State Forestry Service and curated IABR-2014 with the theme Urban-by-Nature. His book publications in English are Landscape (1998) and Greetings from Europe (2008), and most recently, Landscape and Energy (2014).

Sijmons was in Australia courtesy of Brickworks and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects .

This article is part of Foreground’s 2 Degrees themed series of essays