Detoxing the river: toward a swimmable Yarra

The pollution of the Yarra River, Melbourne, is legendary, but new attitudes embracing ecological interconnectedness, Indigenous knowledge and adventurous design optimism are producing collective visions of a new, swimmable city playground.

Sam Wallman, Melbourne comic journalist and political cartoonist, documents the experience of Melbourne’s Yarra River in his illustrated work Seed Water. He highlights the long and overlapping, but often invisible, history of the Yarra and the reflections upon self and society that river proximity inspires. It is a powerful work that encourages us to contemplate how the toxic river narrative ‘…became part of our collective understanding of these spaces’.

The idea that the Yarra River is polluted permeates our relationship to it. It’s implied in a settlement history of turning-our-backs-to-the-river, the tut-tutting when Australian Open winners have a celebratory dip, and the vox pop incredulity generated by river swimming stories. Dirty, murky, broken, brown, upside-down beleaguered Yarra. Isn’t it time for a different story?

And yet every Yarra pollution story has needed to identify a cause and a response. Newspaper reports from the mid to late 1800s point to the noxious industries lining the Yarra – fellermongeries, tanneries and woolwashing houses – as the main culprits, despite legislation having made these illegal. A paper mill was named a major river polluter in the 1900s, but continued operation as it was ‘most vital…to the progress of the State’: the price of progress.

The Allen’s Sweets factory on the Yarra River opposite Flinders Street Railway Station. Familiar to older Melburnians for a ‘sickly sweet smell and the steamroller juice that floated on top of the Yarra’s water’. Ceased production 1987.

As industry on the river banks eventually closed, river health remained poor, and so the blame shifted. Through the mid to late 20th century, dumping of poison and sewerage discharges were to blame, but proper sewering and river rangers would fix that. State politicians argued about whether dog or human poo was responsible for the pollution in the 2000s, and jokingly reminisced about the ‘sickly sweet smell and the steamroller juice that floated on top of the Yarra’s water’ from the old Allen’s riverside factory which ceased production in 1987. Like many urban waterways, the Yarra has been a rubbish dump, a moving tip, laden with toxic heavy metals and human sewage. It has definitely had bad publicity.

Although a loyal documenter of collective Yarra outrage, the press have also been integral to advocating for its repair. In the 80s, The Age ran a spirited campaign called ‘‘Give the Yarra a Go!”, reprised for critical comment in 2005. The campaign called for a number of improvements to the Yarra, many of which we now enjoy, and others yet to come: improving water quality, turning a carpark into a park, installing walkways and bike paths along the Yarra, and streamlining the tangled flows of river governance. But implicit in the campaign title is the complexity of ‘fixing’ the Yarra. As well as legislative and practical responses, the Yarra needed something more; it needed people to give it a go, to care, to love it, to attach other emotions to it beyond repulsion and apathy to start to pay back the price of progress.

Traps along the lower reaches of the slow-flowing Yarra collect floating pollution and rubbish

Litter traps along the Yarra River not only collect gross pollutants but serve as public education and advertisement.

Litter traps on the Yarra River capture tonnes of waste from entering the nearby bay.

Imagining improvements continues to underpin efforts to connect people to the future of the Yarra. Informing the Yarra Strategic Plan, to be launched later this year, Imagine The Yarra drew ordinary Melburnians into workshops and public forums, revealing the vast human connections to the whole river, from the source to the mouth. Writers, designers, architects, community leaders, entrepreneurs, walkers, dreamers, swimmers and First Nation elders all gathered to have their say and tell their story. Because, despite the persistence of the toxic river narrative, people have always cared about the river. And it is clear they still do, evidenced by landmark legislation in 2017 recognising the Yarra River, and the many hundreds of parcels of public land it flows through, as one living, integrated natural entity deserving protection and improvement.

The conversation seems to be changing and we just might be witnessing a significant shift in our collective understanding. The Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 legislates for a different way of thinking about the river. Written in English and Woiwurrung, the language of the Wurundjeri, the Act enshrines the voice of Traditional Custodians, their knowledge and culture. Although it stops short of giving the Yarra actual rights, as has happened in New Zealand and elsewhere, it does regard the river as a single entity; a step towards shedding the fragmented view of the Yarra and fragmented responses to river health. The Act also establishes the Birrarung Council, providing a much-needed independent voice for the river’s interests.

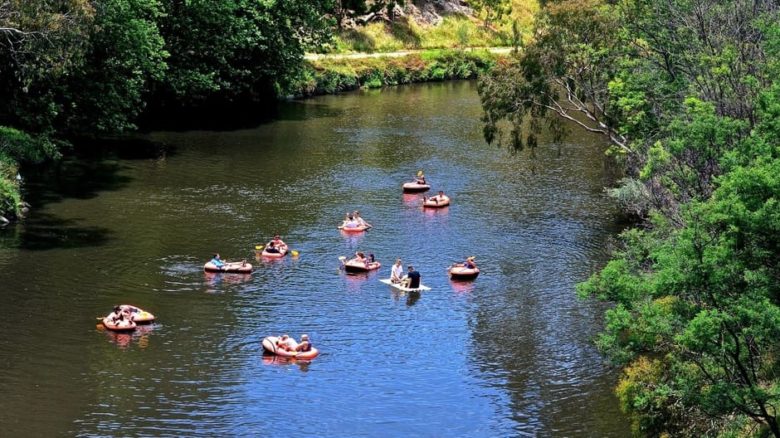

'Inflatable Regatta' started in 2016 and has become a popular regular event on the Yarra River. Photo: Inflatable Regatta

The 'Inflatable Regatta' lets you float on the wide Yarra, close to the cool water. Enjoy with a friend!

Posters advertise the popular 'Inflatable Regatta' in Melbourne - a fun, safe, sensory-rich experience of an urban river.

Some of the Inflatable Regatta on the Yarra River in Melbourne, a city of 5 million people. Photo: Inflatable Regatta

The facts of water quality remain, but efforts to clean the river also call to our sensory side. The Inflatable Regatta, now an established event, started in 2016 with a few friends planning a bit of fun. But they suddenly found themselves inadvertent experts on river health and safety regulations after their Facebook event went public. A float down an urban river a tradition of many an Australian country camping trip – struck a chord with many city dwellers.

The proposed Yarra Pool project does this too, by invoking an intimate connection to water and a space for gathering and play. It’s a credit to decades of river improvements and grass-roots effort from groups like the Yarra Riverkeeper Association, that people would even dare dream of a river float down, relaunching an old swimming race, or developing a riverside pool.

In their study of nature and society, Contested Natures, sociologists Phil Macnaghten and John Urry argue there isn’t one objectively definable ‘nature’, but multiple natures, and our culture and society often constructs different meanings around each one. Human feelings about nature, they assert, are embedded in time and space, subject to the influence of the senses and construction of environmental ‘goods’ and ‘bads’. Our feelings about the river are an example of this. There’s not one Yarra, there are many Yarras. The Yarra of the past is different to the Yarra of the present. The Yarra in the Yarra Ranges is the same river as the Yarra in the city, but different locations are often understood quite differently. Clear, delightful, healthy and good further upstream, dirty, dangerous and bad in the city.

The proposed lap pool on the Yarra River, Melbourne by Yarra Pools and WOWOWA. Image: WOWOWA

Lush vegetation by the proposed cafe and pool by Yarra Pools and WOWOWA, Melbourne. Image: WOWOWA

Bird's eye view of Yarra Pools and WOWOWA proposal for swimming on the Yarra. Image: WOWOWA

A lap pool on the Yarra River, Melbourne by Yarra Pools and WOWOWA. Image: WOWOWA

“We have to rewild the landscape to rewild the river,” says Michael O’Neill, President of Yarra Pools. ‘Rewilding’ seems at once a risky and compelling strategy and is growing in Australia and around the world. It requires a giving-over-to-nature and a loosening of the control and neatness that civilisations have previously pursued resulting in hard river edges and straightening of natural river courses. Yarra swimming clubs, dotted along the Yarra in the early 20th century, used concrete to engineer enclosed river swimming areas such as at Alphington and Deep Rock Swimming Pool. Like the proposed Yarra Pools, community groups were often involved in the construction and running of these clubs, albeit their main focus was keeping people safe from drowning. Yarra Pools has developed a proposal with both the needs of people and the needs of the river in mind. ‘Towards a swimmable Yarra’ is their their byline. The group’s latest design, created in collaboration with WOWOWA Architecture, proposes a naturalistic approach to water frontage, softer and alive with plants.

This 2016 Melbourne Water video explains the critical role the release of environmental water plays in the ecological management of Melbourne’s iconic Yarra River.

These new visions of the Yarra do not gloss over challenges to make a city river swimmable or more wild, or ignore human responsibility for pollution. But new visions work towards reframing our collective understanding of river spaces and possibilities, and they share an undercurrent of responsibility and custodianship, of awe and humility. And while legislations seeks to reframe it from the top, community groups work from the bottom up, imagining riverside city pools, a rewilded urban edge, a float down towards the CBD. These connect us to the river, getting us near enough to know it better, maybe love it, and want to care for it. We might even give it a new go.

–

Sally McPhee collaborates on projects engaging people in culture, nature, art and place. She has worked with the Arts Centre Melbourne and the Betty Amsden Participation Program (2013 – 2018). She graduated from RMITs Urban and Regional Planning Honours program in 2016, completing a thesis on the early 20th Century history of swimming in Melbourne’s Yarra River. Sally currently works with Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria on placemaking and interpretation projects and co-curated the Waterfront program with Open House Melbourne for Melbourne Design Week 2019.