Why can’t you grow food wherever you want?

While the street-side fresh produce vendor is a romantic image, Jennifer Kent points out the myriad reasons why cities aren’t replete with nature-strip verges.

Food provides the foundations for human flourishing and the fabric of sustainability. It lies at the heart of conflict and diversity, yet presents opportunities for cultural acceptance and respect. It can define neighbourhoods, shape communities, and make places.

In parts of our cities, residents have embraced suburban agriculture as a way to improve access to healthier and more sustainably produced food. Farming our street edges and verges, vacant land, parks, rooftops and backyards is a great way to encourage an appreciation of locally grown food and increase consumption of fresh produce.

Despite these benefits, regulations, as well as some cultural opposition, continue to constrain suburban agriculture. We can’t grow and market food wherever we like, even if it is the sustainable production of relatively healthy options.

While good planning will be key to a healthier, more sustainable food system, planning’s role in allocating land for different uses across the city also constrains suburban agriculture.

A farmer's market at CERES, a sustainability centre and urban farm in Melbourne.

A summer garden at Sydney Park.

Glover St Community Garden, Sydney.

The Carriageworks weekly farmer's market, Sydney.

Two steps towards healthier food systems

Making our food systems healthier and more sustainable requires a two-step approach.

• First, we need to fortify the parts of the system that enable access to healthy food options.

• Second, we need to disempower elements that continuously expose us to unhealthy foods.

Although food is a basic human need, the way we consume food in many countries, including Australia, is harmful to the environment and ourselves. Many of us don’t eat enough fresh and unprocessed foods. The foods we do eat are often produced and supplied in carbon-intensive and wasteful ways.

Primarily through land-use zoning, town planners can help to shape sustainable and healthy food systems. For example, good planning can:

• protect peri-urban agricultural lands;

• encourage farmers’ markets, roadside stalls and community gardens;

• prevent the location of fast-food outlets near schools; and

• even help regulate food advertising environments.

Why have land-use zones?

Modern town planning originated in the 19th century out of the need and ability to separate unhealthy, polluting uses from the places where people lived.

This was a direct response to the Industrial Revolution, which brought with it both an upscaling of the noisy, smelly and dirty uses to be avoided, and the emergence of new ways to travel relatively long distances away from these uses.

As a result, our urban areas are made up of a mosaic of what we call zones. Within each zone, certain uses are permitted and others are prohibited. If a piece of land is zoned as commercial, for example, that land can be used for a shop, but not for a house.

While this might seem logical to us today, to those living in housing scattered among the factories and tanneries of Manchester in the 1800s it would have been quite radical.

It is this function of planning that means we cannot grow food anywhere in the city. Instead, we have regulations that attempt to ensure related activities occur only in areas where such a use is compatible with the surrounding uses.

Incompatibility might relate to safety. For example, in some cities it is prohibited to locate a community garden on a main traffic-generating road due to concerns about contamination of produce.

It could also be related to amenity. For example, in some areas local produce cannot be sold on the roadside due to concerns about creating additional traffic and parking.

These are two fairly obvious examples, but problems arise when definitions of what is safe and amenable differ within the community. Does a verge planted with an over-enthusiastic pumpkin vine detract from or enhance the visual appeal of the street? Should a locality embrace a roadside produce stall even if it means traffic is slowed and parking is less available?

”We need to disempower elements that continuously expose us to unhealthy foods”

Landscape architects have the ability to influence zoning food advertising environments.

MoMA PS1's Public Farm 1 (PF1). Image: Work Architecture.

MoMA PS1's Public Farm 1 (PF1). Image: Work Architecture.

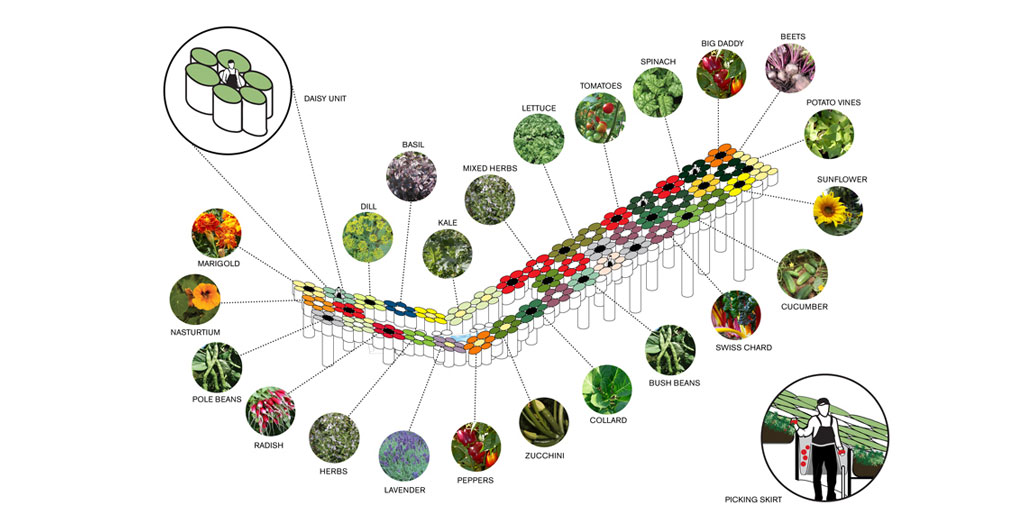

Public Farm's plant varieties. Image: Work Architecture.

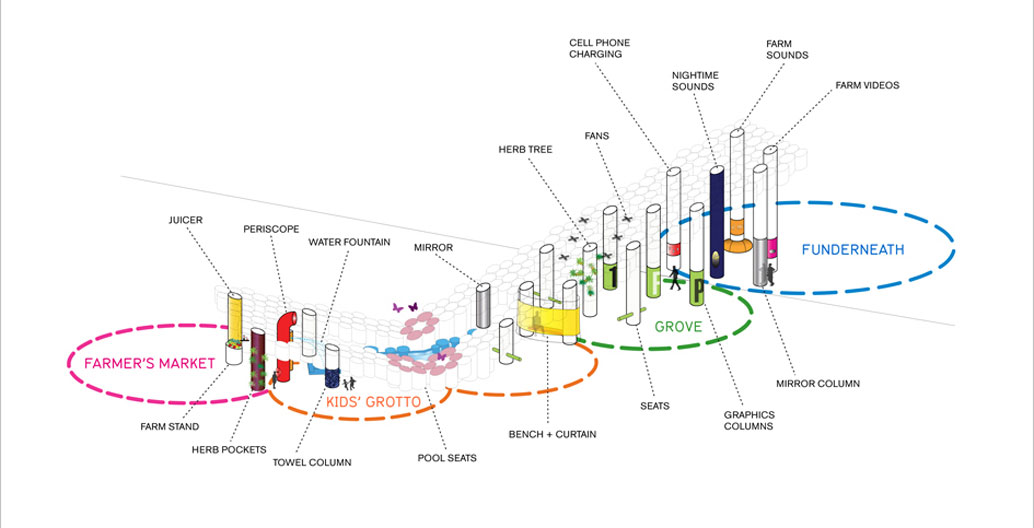

How the farm works. Image: Work Architecture.

How do we resolve planning conflicts?

Town planners attempt to grapple with these issues by developing new policies and regulations to respond to changing demands, or by assessing applications for food growing and distribution on a case-by-case basis.

In cities that are rapidly densifying, and in a cultural environment where growing one’s own produce is enjoying a renaissance, it’s not surprising some local authorities are struggling to keep up.

This struggle is ostensibly the result of local authorities failing to recognise and prioritise their role in supporting sustainable and healthy food systems. There are immense benefits – biophysical, economic and social – to be gained from local government giving priority to urban agriculture.

Yet a recent study of the content of local community strategic plans across New South Wales found that only 10% of strategies mentioned anything about food systems as a community priority. In this sense, Australia is part of an international trend.

Surprisingly, the local authorities in New South Wales doing the most for better food systems were regional councils. These saw food security and the opportunities presented by local food production as urgent issues. There is obviously room for our metropolitan councils to catch up and capitalise on increased cultural interest in farming our suburbs.

——

This article was first published via The Conversation.

Dr Jennifer Kent is a research fellow at the University of Sydney. Her research interests lay primarily in the intersections between planning and health, including planning for active transport and attachments to the private car as a form of mobility.

![]()