Australia, you have unfinished business. It’s time to let our ‘fire people’ care for this land

The royal commission into Australia’s bushfires recognises the potential of Indigenous knowledge in fire management, but recognition is only the start. Traditionally western structures for fire management need to include Aboriginal people, knowledge and value systems.

Since last summer’s bushfire crisis, there’s been a quantum shift in public awareness of Aboriginal fire management. It’s now more widely understood that Aboriginal people used landscape burning to sustain biodiversity and suppress large bushfires.

The Morrison government’s bushfire royal commission, which began hearings this week, recognises the potential of incorporating Aboriginal knowledge into mainstream fire management.

Its terms of reference seek to understand ways “the traditional land and fire management practices of Indigenous Australians could improve Australia’s resilience to natural disasters”.

Incorporating Aboriginal knowledge is essential to tackling future bushfire crises. But it risks perpetuating historical injustices, by appropriating Aboriginal knowledge without recognition or compensation. So while the bushfire threat demands urgent action, we must also take care.

Accommodating traditional fire knowledge is a long-overdue accompaniment to recent advances in land rights and native title. It is an essential part of the unfinished business of post-colonial Australia.

A living record

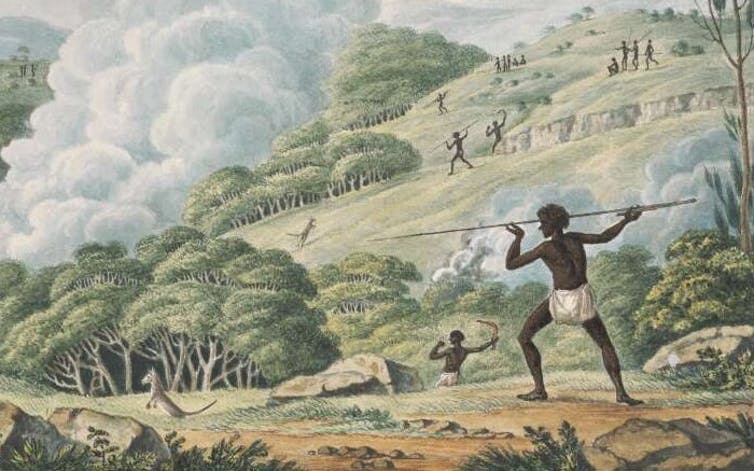

Before 1788, Aboriginal cultures across Australia used fire to deliberately and skilfully manage the bush.

Broadly, it involved numerous, frequent fires that created fine-scale mosaics of burnt and unburnt patches. Developed over thousands of years, such burning made intense bushfires uncommon and made plant and animal foods more abundant. This benefited wildlife and sustained a biodiversity of animals and plants.

Following European settlement, Aboriginal people were dispossessed of their land and the opportunity to manage it with fire. Since then, the Australian bush has seen dramatic biodiversity declines, tree invasion of grasslands and more frequent and destructive bushfires.

In many parts of Australia, particularly densely settled areas, cultural burning practices have been severely disrupted. But in some regions, such as clan estates in Arnhem Land, unbroken traditions of fire management date back to the mid to late Pleistocene some 50,000 years ago.

Not all nations can draw on these living records of traditional fire management.

Indigenous people around the world, including in western Europe, used fire to manage flammable landscapes. But industrialisation, intensive agriculture and colonisation led to these practices being lost.

In most cases, historical records are the only way to learn about them.

Rising from the ashes

In Australia, many Aboriginal people are rekindling cultural practices, sometimes in collaboration with non-indigenous land managers. They are drawing on retained community knowledge of past fire practices – and in some cases, embracing practices from other regions.

Burning programs can be adapted to the challenges of a rapidly changing world. These include the need to protect assets, and new threats such as weeds, climate change, forest disturbances from logging and fire, and feral animals.

This process is outlined well in Victor Steffensen’s recent book Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia. Steffensen describes how, as an Aboriginal man born into two cultures, he made a journey of self-discovery – learning about fire management while being guided and mentored by two Aboriginal elders.

Together, they reintroduced fire into traditional lands on Cape York. These practices had been prohibited after European-based systems of land tenure and management were imposed.

Steffensen extended his experience to cultural renewal and ecological restoration across Australia, arguing this was critical to addressing the bushfire crisis:

The bottom line for me is that we need to work towards a whole other division of fire managers on the land […] A skilled team of indigenous and non-indigenous people that works in with the entire community, agencies and emergency services to deliver an effective and educational strategy into the future. One that is culturally based and connects to all the benefits for the community.

Making it happen

So how do we realise this ideal? Explicit affirmative action policies, funded by state and federal governments, are a practical way to protect and extend Aboriginal burning cultures.

Specifically, such programs should provide ways for Aboriginal people and communities to:

- develop their fire management knowledge and capacity

- maintain and renew traditional cultural practices

- enter mainstream fire management, including in leadership roles

- enter a broad cross section of agencies, and community groups involved in fire management.

This will require rapidly building capacity to train and employ Aboriginal fire practitioners.

In some instances, where the impact of colonisation has been most intense, action is needed to support Aboriginal communities to re-establish relationships with forested areas, following generations of forced removal from their Country.

Importantly, this empowerment will enable Aboriginal communities to re-establish their own cultural priorities and practices in caring for Country. Where these differ from the Eurocentric values of mainstream Australia, we must understand and respect the wisdom of those who have been custodians of this flammable landscape for millennia.

Non-indigenous Australians should also pay for these ancient skills. Funding schemes could include training, and ensuring affirmative action programs are implemented and achieve their goals.

Involving Aboriginal people and communities in the development of fire management will ensure cultural knowledge is shared on culturally agreed terms.

Fire people, fire country

In many ways, last summer’s fire season is a reminder of the brutal acquisition of land in Australia and its ongoing consequences for all Australians.

The challenges involved in helping to right this wrong, by enabling Aboriginal people to use their fire management practices, are complex. They span social justice, funding, legal liability, cultural rights, fire management and science.

Fundamentally, we must recognise that Aborigines are “fire people” who live on “fire country”. It’s time to embrace this ancient fact.

Andry Sculthorpe of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre contributed to this article.

David Bowman is a Professor of Pyrogeography and Fire Science, University of Tasmania. Read Foreground’s interview with him, November 2019, here.

Greg Lehman is the Pro Vice Chancellor, Aboriginal Leadership, University of Tasmania.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()