After architecture: Marco Poletto on designing systems for dark ecologies

From algal bioreactors, to urban waste streams and the transcontinental migratory flows of birds, Marco Poletto’s EcoLogicStudio is opening up vital new territories of exploration for environmental design.

EcoLogicStudio describe themselves as an architectural and urban design practice, but the work they produce, and the means by which they produce it, bears little if any resemblance to the conventional understanding of what might constitute architecture.

Founded in London in 2005 by Claudia Pasquero and Marco Poletto, the practice’s interest in what they describe as the “ecologic city” has seen them develop a hybrid practice that deploys digital tools and simulations to “build” with living systems and biological materials, such as algae, with “site conditions” that are often of a transcontinental scale. All of their work is defined by a commitment to exploring, and exposing, the dark ecologies that underpin our urban environments, towards a genuinely sustainable model of design and development unburdened by dualistic or picturesque notions of the human and natural.

In this interview, conducted at the Melbourne School of Design in February 2020 just before the world’s borders began to shut in response to the burgeoning coronavirus pandemic, Poletto expands on his unusual hybrid practice and our urgent need to engage with the dark side of urbanization.

***

Foreground: How did you land on algae as a design medium?

Marco Poletto: It came out of an attempt to materialise a form of drawing in 2005, 2006. At the time, we were doing a lot of drawings and simulations of environmental factors—so we were trying to draw the invisible, if you like, the kind of elements that often escape the tectonics of architecture but are actually profoundly spatial, like thermal gradients.

So we were drawing those through the new techniques of digital design that had become available: simulations and other ways of drawing fields. At some point we were like, “Okay, if you have a gradient of light in this room and you have something here that registers that light, what could that be?”

Obviously, you could have sensors, you could have humans, but then we realised that plants responded to the gradients—they’re phototropic, they move, they react to them. But we wondered, what if we go to the microunit? Something that could translate our drawing into the physical, biological, living world—essentially, a bit of digital information. And so we arrived at algae.

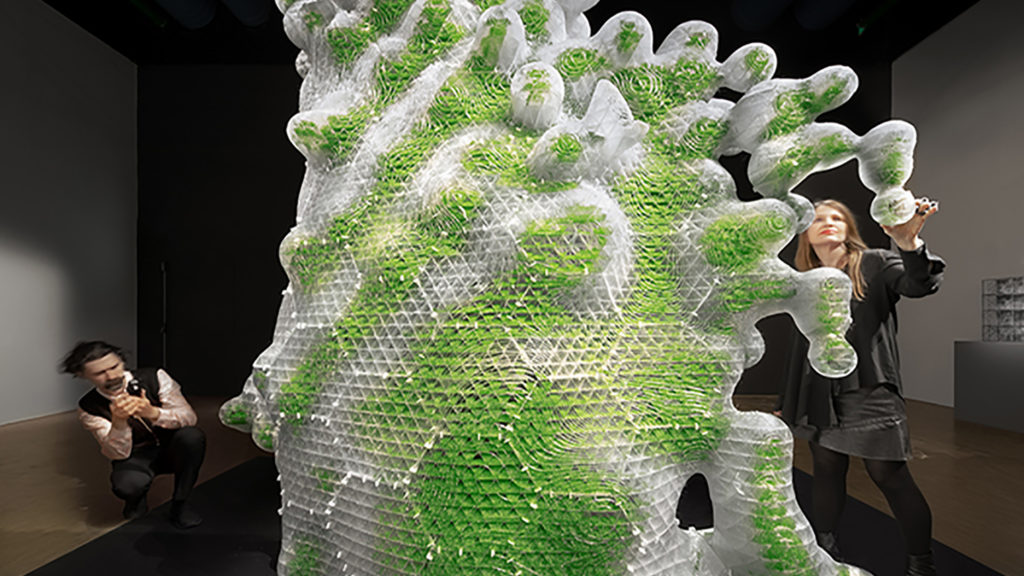

This became almost like a game of translating information into living material. So we started quite intuitively to create a series of installations. The first one was very simple: a series of screens in a gallery made out of bottles stacked on each other. Then we quite literally took it as a simulation of light radiation in the room, as a kind of map to bottle the algae into this container with different densities that were responding to the density of light. So we created a sort of biological map of light intensity. The idea was that the algae would respond to that and eventually grow, and so what was in the computer as a simulated abstraction would translate into something more complex.

You could say that algae were the perfect abstract organism in the encounter between our interest in biology, living systems, complex systems and, on the other side, simulation and digital culture as a way of expanding on our understanding of that world.

Foreground: The interest in algae began with a hunt for a material element that would be environmentally responsive and adaptive to its environment.

Marco Poletto: Yes. Often people ask if we are against planting trees and so on, and no, of course not. But at the time we felt that the way plants and trees were brought into the urban realm was symbolic, whereas we were interested more in the performative—not in the reductive sense, but as an understanding of how nature becomes an active layer of the urban landscape that is both spatial, material and also infrastructural in a way. How it kind of plugs into the overall metabolism of the city.

So in that sense, we like algae because of the fact that they are microorganisms and that not only makes them particularly efficient in certain embodiments, but also makes them kind of abstract in a way, with respect to the tradition of urban nature or landscape. It gave us the freedom to use them as a material translation of these simulations we were doing.

Foreground: There’s an interesting connection to the history of artificial intelligence studies, those very early games that developed self-replicating digital organisms.

Marco Poletto: One of the first comments we received was in 2008 at the AA where we’d done an installation. The director at the time was Brett Steele, who saw the piece and said, “Oh, this looks like a pixelated nature.” He was spot on in a way. It was really an attempt to kind of fuse these two worlds for us. The idea of pixelated nature is a nature that enters a certain level of abstraction and therefore disconnects from the idea of the picturesque and gets more hardwired into these infrastructural, digital processes that drive contemporary organisation in cities.

Foreground: It’s obviously quite a potent aesthetic, what you’ve developed there with the algae, unintentionally or otherwise. With a lot of the built work that you have completed there is almost a sci-fi feel to it, aesthetically. Is that a deliberate decision? Do you see your work sitting in that speculative fiction tradition? In the architectural context, a lot of that tradition is really about a kind of provocation. It’s not really intended to be built as such; it’s not intended to have a real-world application. Is that the way you see your practice developing?

Marco Poletto: This is a very important point because for many years, we never really wanted to talk about aesthetics. Not because we were not interested in it, but because for us it was a really part of the artistry of designers, while our focus was more on the development of these material systems. We were interested in the systemic approach so we didn’t want to talk too much about aesthetics because then it was very much related to the idea of style and all of that.

But recently we started to realise that the aesthetic elements are pretty crucial in many ways. It’s not so much connected to the idea of style, or provocation through image, but rather to the idea that aesthetics, in our mind, are very much a measure of ecological intelligence. In many living systems, the patterns that they exhibit, which we often recognise as beautiful, are essentially a manifestation of their internal organization, or the way they deal with material flows, the way they manage to optimise—they are performance-related. It’s a kind of evolutionary trait that emerges out of their interaction with the environment.

For me, that could also be said of the architecture that we tried to produce. In a way, we feel that developing a certain language is a way of enhancing its ability to communicate with different systems. So communication that is not just essentially digital, but also through a language that people can relate to. Maybe it provokes them, but in a sense of a questioning of their assumptions about the concept of nature, or the relationship between nature and the built environment.

What does it mean for architecture to be green, and sustainable, and so forth? We are committed to having an impact so maybe there is a different attitude to what might have been the attitude of some radical groups, like Archigram or others that were bringing nature into the drawings in a provocative way. There is different urgency, I think, today. That urgency should not let us forget that in order to have an impact, we still need to go through a cultural transition—it is not just a question of applying new technologies.

Foreground: That idea of urgency is a nice segue to my next question, which has a relationship to this idea of science fiction. Have you ever read the book The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi? It was published around the time Timothy Morton started getting interested in this concept of dark ecology, which I’m assuming informs your work to a degree.

Marco Poletto: It is certainly influential to us. Yes.

Foreground: The Windup Girl is a science fiction story about a post-oil world, where the primary means of generating resources is biotechnology—in particular, algae. The book has a dark ecological timbre, but a lot of these algae-based technologies, being living technologies, run out of control, so from that perspective it is a dystopian story. There is a very strong strain of dystopian thinking, too, to what Timothy Morton is saying—he talks about “the catastrophe that has already happened”, the implication being that now we just need to wait and see how it all plays out. There’s an element of control, but a lot of it’s out of our control.

From that perspective, a lot of your aesthetic, like the slime mould that you showed last night, and even the algae, which is this incredibly almost unnaturally bright green, could be quite confronting for people. Is that part and parcel of your sensibility, that confrontation?

Marco Poletto: As designers, I don’t think we can really afford to be dystopian today. There is definitely a more positive outlook in the way we think these techniques can be applied—not because we think they are the best technologies in the world, and if we apply them they will save us, but because they are a chance to open up a window into the unknown, or a window into the natural world that we are now realizing we have been misunderstanding for most of modernity.

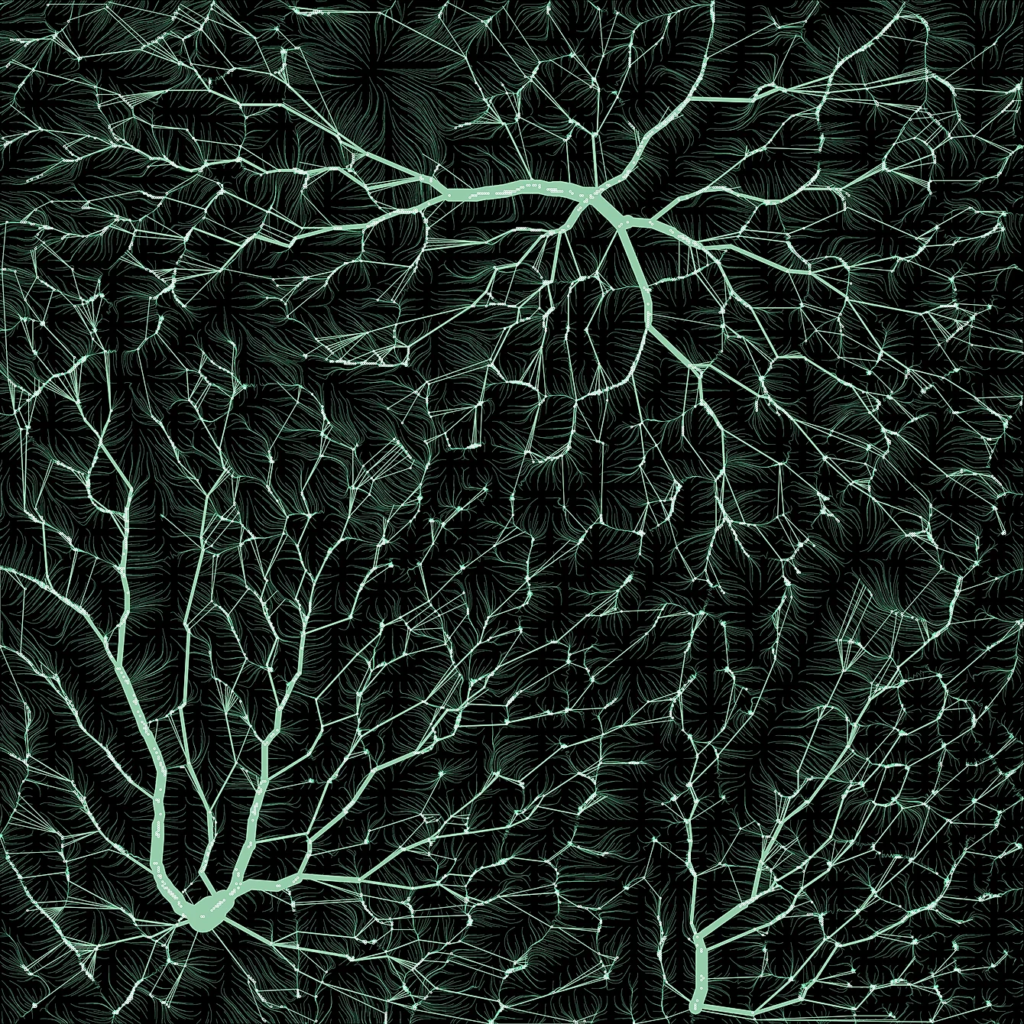

For me, these elements are elements that people need to be confronted with, so in a way bringing up these sides of nature that people think are disgusting, or normally don’t see, it’s critical. But at the same time our aesthetic is not meant to scare people away, or give you a sense of anxiety. It’s actually meant to instigate a deeper level of connection with the natural world, and therefore with the multiple levels of intelligence that exist and the way in which the natural world operates, which is often radically different from the way we’ve been operating. For instance, the way we design infrastructure from the point of view of the distribution of resources versus the way slime mould would do it, it’s completely different.

First of all, we should become comfortable or curious about this dark side of urbanization, which has to do with all these aspects of matter, information and energy that essentially feeds the city, maintains the metabolism of the city, but that we don’t see because we have moved them out of sight because we consider them as dangerous or disgusting.

This goes back to what, for me, is the main issue with regreening or rewilding cities. Every city in the world now wants to plant a million trees, which is fine, of course. But at the same time, I ask myself, when you plant a tree in a city, what is it? Are you creating a forest or are you creating a piece of urban infrastructure? And if that’s a new piece of soft urban infrastructure, what are the performance characteristics? Can it process pollution for you and re-metabolise it? Can it digest waste for you? What kind of urban landscape does it become part of?

You never see these trees being planted into landfills, or a drawing that describes how a landfill is not just covered with green trees, but actually trees become a way of re-metabolizing the mucky reality of the landfill itself. The interface between these two realms is never drawn, it’s never explored because we don’t want to see it. So when people see it, they don’t think there is landfill, they just think it’s a green mountain. We forget about what’s inside, and that’s precisely the problem of sustainability today: you can’t be sustainable if you forget what’s inside the mountain.

If we have mountains of waste and plastic, then what kind of mountains are they? Do they become part of a new kind of landscape, and what kind of landscape is that? Can we design it? Can we evolve it in some way? Can we digest it, could it be recycled, can this become part of a new stream of resources and raw materials?

Foreground: You’ve described your project in Guatemala City in the context of rewilding. Guatemala City suffers from this incredible garbage problem, and there is an entire community that has grown up within that garbage. “Rewilding” has very particular intonations when you talk about it in the conservation context. It’s freighted with this idea of a kind of natural equilibrium. It talks about reintroducing wild species, predator species into a space to achieve that equilibrium. I don’t get the sense that that’s what you’re considering doing in Guatemala City. So how is rewilding translating into that context?

Marco Poletto: Guatemala is a very peculiar but also significant case study. The morphology of the city is such that there are these deep valleys that cut through the city, which are essentially green valleys with a lot of vegetation that grows very quickly. But they also naturally became open air landfills, because the city had very bad waste management, so things were just dumped down the valleys and started accumulating to a point at which the water would not flow out anymore.

So you start to have flooding, and you start to have erosion, and you actually had consequences that go much deeper into the city and that create a lot of instability and fragility in the whole urban system. In that sense, it is a clear example where this dark side of the city cannot be invisible, as we would like it to be, because it’s manifesting itself over and over again in the city.

But then there is the other side of the story, where out of extreme necessity a lot of people have inhabited these areas and have begun a process of sorting and extracting material that they sell on for very little. Of course, the price they pay with their health is enormous and it is an unacceptable situation.

I think that demonstrates how in such a situation rewilding needs to start from waste management, needs to start from strategies that have much more to do with the infrastructural layer. And so a lot of the work we’ve done has been in terms of mapping and diagramming urban infrastructures and waste management, and trying to create a sort of interface that would recognise these local, informal or emergent realities, in order to enable a process where funds, investment, support can go to these realities so that this community could perhaps continue to do what they are doing, but in an acceptable condition.

For me, it’s about the recognizing the dark side that nobody wants to see, which is in this case connected not just with environmental degradation, but also with poverty and health issues, and trying to understand how these mechanisms can become instead a positive engine. The first step is to recognise the existence [of the condition], map it, draw it, bring it to local administrators, but also international attention, and begin to channel funding to the specific problem. The planting of trees, the introduction of other systems would follow.

There is actually a lot of wildlife around Guatemala City. Like many people, it’s displaced from the countryside and from the wild because of the large-scale industrial agriculture that is taking place. The city is becoming a refuge, if you want, for displaced people and wildlife. That is an interesting inversion of what we normally think of the city, as a kind of agent of environmental degradation.

Foreground: So from that perspective, the rewilding for you begins from the point at which we recognise there’s a metabolic exchange taking place, which is close in many ways to the kinds of exchange we might see within a so-called natural system.

Marco Poletto: From the recognition that there is a dark side of nature, that nature is not only green. And so these valleys where rubbish has been piling up in the middle of trees and waterways, and people have been coming in and trying to rescue material, that is nature. That is a manifestation of a contemporary landscape where different forms of biological nature, human, non-human, technological by-products of urbanization, agriculture and so on have come together.

Foreground: It’s an emergent system driven by a kind of dynamic necessity. You’ve talked about the birds that travel from Canada down to Guatemala City and back annually. What I found compelling about that was it seemed to allude to a kind of radical shared responsibility, a radical neighbourliness, if you like, wherein suddenly people living in Canada have a relationship with people living in this trash pile, ultimately, in Guatemala City, and a need to look after that environment as much as they look after their own environment. Was that intentional?

Marco Poletto: That is correct. In the last few years, we started to engage with a few projects [like this], like the salina [salt pan farm] that was abandoned in Montenegro that became a stopover for birds immigrating from Europe down to Africa. That project was in a way quite similar, because you have a location in which there’s poverty, linked to countries that are completely different in terms of their wealth and organization by a very direct thread, which is the immigration of these birds. If the thread is broken, the biodiversity up in the developed countries is affected quite drastically. In the case of Montenegro there has been direct intervention from the European Union on that site to somehow force the government in Montenegro to intervene and stop poachers killing the wildlife.

So in that sense, in Guatemala City we started to imagine that a process of regreening or rewilding could have made the city a significant node in the journey of these migrating birds, and therefore reinforced the link with these other countries that are along that journey.

It’s another dimension of the idea of rewilding that that could be explored. It’s about looking at different layers and scales that often go beyond the boundary of the city, even of the country; we’re really talking about transnational, transcontinental logics.