From grey to green infrastructure: How local governments are re-making Melbourne

Melbourne’s understanding of the value of green space has changed dramatically over the past 10 years, thanks in part to the quietly determined advocacy of public sector landscape architects. ASPECT Studios’ Kirsten Bauer speaks to three designers charting this tricky territory.

The following conversation is an edited transcript from Foreground’s ‘Living with water: Design for uncertain times’ forum held as part of Melbourne Design Week at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Kirsten Bauer: What’s interesting is that all three of you are in a sense “embedded” in the system. Often we talk about fighting the system. How do you think you’ve been most effective in that environment, in a sense not speaking to the converted?

Ian Shears (City of Melbourne): There have been a couple of aspects to why the City of Melbourne has been so successful in the body of work that it’s produced. At the heart of it, we’ve taken the long term view and recognised that our intention is to make 100-year decisions. So it’s about leaving a legacy and it’s about getting your organisation to ask, “How do you get those politicians into a 100-year legacy?” It makes them look good… put the Lord Mayor on a stage in New York with Michael Bloomberg and he’s fairly happy.

What we needed to think about was the future rather than just the present, taking people away from short term and often selfish thinking. Instead of a 12-month financial cycle or a three-year political term, we moved to one of “future generations”, which we managed to get both bureaucracy and the community to buy into.

KB: And also having photo montages showing the death of all Melbourne’s elms in the boulevards would’ve helped.

IS: It was also demonstrating the value of it. What we said is that if you invest in green infrastructure, that’s the best response. We did international reviews which said the smartest thing you do to respond to the heat island, which is also the cheapest and most effective, is to plant trees. New York worked out that for every dollar they invested in their urban forests they got a return of $5.60.

Urban tree plantings are proven to reduce heat and pollution.

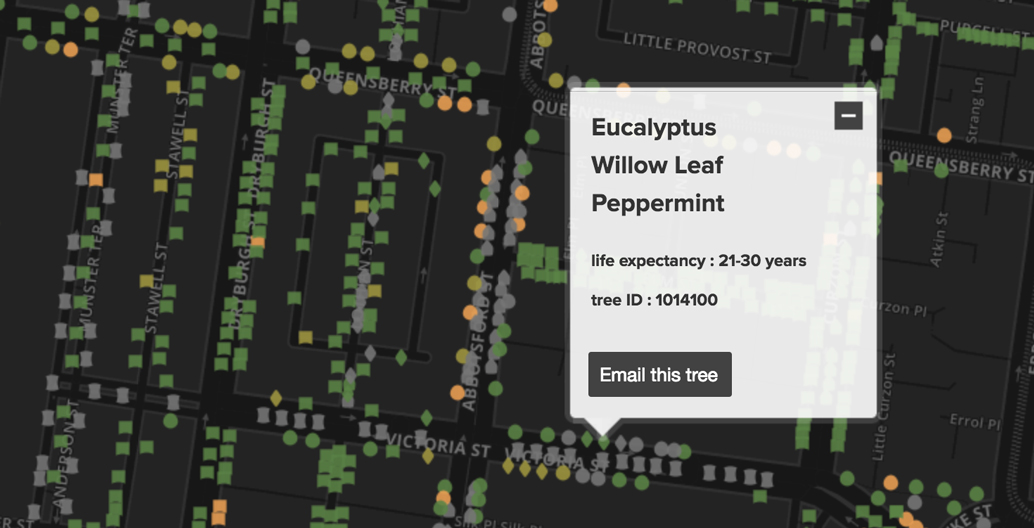

You can log onto the City of Melbourne's Urban Forest Visual and email every single tree in the municipality.

An intensive wall of green at Melbourne's Fitzroy Gardens.

KB: So some of that messaging turned into metrics?

IS: Yes, but you also had to embed community values in decisions. When the community wants something, it’s very hard to go against. While you can produce a really fantastic piece of work, it might just sit on a shelf. The question then becomes: how do you stop it just sitting on the shelf?

KB: Adrian, I was reminded of the way you reframed Brimbank’s typical “we need more open space” narrative. Instead, you started talking about why people don’t use parks. So you flipped the narrative I suspect.

Adrian Gray (Brimbank City Council): To get that going in Brimbank, the person in my role previously spent two years as the lone landscape architect in Brimbank, and prior to that, there were no design services provided to the community other than engineering. So he spent two years slogging away at creating better parks, cycling and walking tracks… I remember going to some community open space forums and they just thought this is a joke.

So we had to persevere. We had to get some money. We had to get some wins. So when we went to the first suburban park event with the community, about six people came and said, “you’re not gonna spend four hundred and forty thousand dollars here – no way”. Well, 18 months later we opened the park. Politicians loved it. They could see why this is a good service. So we got into the momentum of delivery.

When Greening the West came along we thought about how it impacts on the community. When we did a survey, we were able to get the data out of that survey and explain it to our politicians. We were able to demonstrate a significant liveability service at a local level.

Measures of socioeconomic and health status are generally poorer in Melbourne’s west.

Tree canopy coverage in Melbourne’s west can be as little as one third that of the city's average.

Melbourne's western suburbs have consistently topped Victorian disadvantage rankings.

KB: Perhaps I’ll indulge the cynic in me: We seem to know what the problem is. We seem to have a fair amount of science about how we should solve some of these problems. We seem to have the technical solutions. So what are the fundamental barriers? And do you see that change occurring or do you still think it’s going to be a long, slow, slog?

IS: Yes it is going to be a slog. But the change is happening. The Infrastructure Australia report that got released the other week talks about social infrastructure, namely increasing the public realm capacity. We know cities are denser. We need to have a stronger resilience capacity in those places. The message is there at a federal level, an independent body…

KB: … which gets ignored on a fairly regular basis.

IS: Let’s hope not.

KB: What’s the high level commentary about what’s stopping us from implementing this?

IS: There’s a value thing around green infrastructure if you think about trees: How do we have Royal Parade all over the city? How does how do we have boulevards with the trees actually the main function for the health benefits that are given? All of that data is there, so making people aware – the Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub (CAUL) is doing a lot of great work about capturing that data and being able to say, “If you do X you’re going to have X”.

KB: Do you think there are still members of the community, and politicians, whom we still need to devise an argument for?

Tashia Dixon (Melbourne Water): Personal values have a lot to do with it. I feel like I work in a very complementary environment – in terms of creating this wonderful green outcome – but sometimes there are competing objectives. So there will be parts of business with a very clear objective to deliver XYZ, but sometimes, that’s not necessarily going to be the same as what another part of the business will have and both of them are very valid. So it’s really about trying to get a balance.

KB: So what stops that balance?

TD: We’re again transitioning all the time and that’s why urban designers are brought in. We’ve got climate change experts now we’ve got environmental specialists we’ve got all these different people… it is a long journey because it’s about people, heart, and values.

IS: The trick is getting a shared vision for the future and once you get a shared vision then everybody can work towards that. We’re having conversations now that we wouldn’t have dreamed of having 10 years ago. So there’s been a rapid transformation. The water sector has been leading that and the culture change that came with Melbourne nearly running out of water – the 155 litres per day campaign was a fantastic bit of change management. Also the understanding of waste of water that falls on the city – where it’s captured, polluted, and put back out to the bay – has also really enabled a lot of change to occur.

But one of the really good opportunities is that we’re starting to see a lot of the previous silos between professions come down in order to recognise the need for a multidisciplinary approach. There’s not one profession that owns change.

Melbourne’s Thompson Dam provides 60 percent of the city’s water supply. 2008 saw its lowest level recorded since construction. Image: Melbourne Water.

KB: I’ve got a tricky question, but you might not think it’s tricky. Sometimes when I’m talking to people about green and blue infrastructure and when we’re talking to our clients as well they’re always saying, “we want green infrastructure, but we live in a dry city”. So if we’re out in the western suburbs, the grass doesn’t stay green during summer. So what is the balance between investing in water sensitive urban design, stormwater capture, stormwater mining all those things to create these green oases in this broader, brown grassland environment? How much do we accept, the “brown” of the Australian landscape, and the desire for the green and cooling city?

AG: If you read Bill Gammage’s book, The Greatest Estate on Earth, whenEuropeans came here it wasn’t brown because it was managed. So now Brimbank is a city and it needs to have a city ecology and sustainable urban landscape. The landscape has to respond to the fact that people are living there and that’s why we’re doing these things with water.

IS: One of the transformative things is the way we’re thinking about green infrastructure is that it’s environmental service provision, rather than say, heritage, or having it because it’s “nice”. Clearly, it’s essential infrastructure. So there’s room for the green and there’s room for the brown, but it’s a matter of making sure we get the green and the brown in the right place and in the right way so it’s sustainable.

––

This conversation was made possible by the National Gallery of Victoria, the University of Melbourne, and the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA).