A significant endeavour: Landscape architecture in Australia’s capital

Few public spaces provoke debate as hotly as Canberra’s National Triangle. Yet the recent collaboration between landscape architect Jane Irwin and architect Philip Thalis, working alongside a larger team of designers, planners and engineers, has proved a circuit breaker – to Canberra’s benefit.

Urban plans invariably assert a set of values on the city, its landscape and its citizens. No one knew this better than the architect and city maker Daniel Burnham, whose foresight and planning largely drove the rebuilding of Chicago after the fire of 1871. A quote from Burnham, cited in Charles Moore’s biography, went on to become a motto for generations of planners that followed him:

Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realised. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency.

Yet how then do landscape architects, urban designers and architects negotiate the values embedded within such big plans, working as they often do, generations later? Canberra after all is the result of big plans with a long chequered history, some more ‘noble’ than others.

Working within a wider collaborative team, including the National Capital Authority, SMEC and AECOM, Jane Irwin of JILA and Philip Thalis of Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects have responded with humility and without further hubris. This is not to suggest the team has put forward little plans; far from it. The plans are aspirational but they are derived from detailed research and respect for those planners, designers and advocates that have gone before. Their plans add to the city’s tangible and intangible planning tropes; adding new layers to the endemic qualities of the city on the limestone plains.

Constitution Avenue

Constitution Avenue transition to landscape of Anzac Parade.

Constitution Avenue civic block at London Circuit intersection.

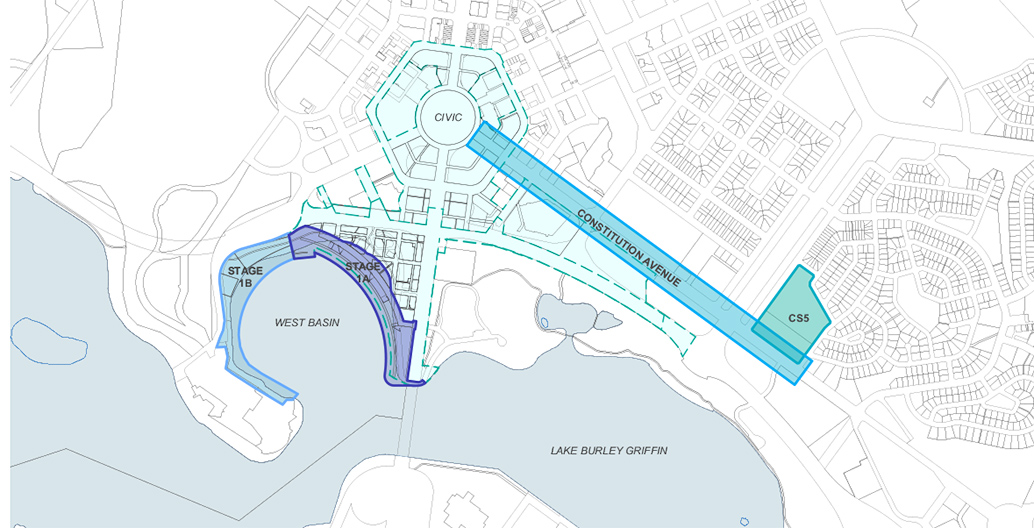

Reference plan, showing the context of both projects

What gives this partnership legitimacy, working in the nation’s capital, is their willingness to grasp the notions of symbolism and significance in an environment where these concepts are passionately tested and contested. The esoteric term ‘significance’ is inextricably bonded to the city’s urban structure, topography, ecology, culture and administration, thanks to the grand plans of Griffins’ winning scheme. Significance is the term used in federal legislation to protect landscape’s place in the national capital narrative. However, significance is also amorphous. It can be subjectively interpreted and used to advocate simultaneously for and against change.

The nuanced approach adopted by Irwin and Thalis dares to engage with disparate views of what significance means. This is not necessarily to find consensus, but rather to engage in a dialogue about contemporary interpretations of landscape and the city.

The controversial West Basin Project, optimistically called City to the Lake, has polarised views in the professional and broader communities of Canberra. As an idea, the project goes back to 2001, when a report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identified the need to create urban vibrancy through the realisation of an urban waterfront. Soon after, the Griffin Legacy project, prepared by the National Capital Authority (NCA), essentially framed an ambitious brief for this project.

The West Basin scheme takes the street and block geometry of the city over Parkes Way, to culminate in a series of urban boulevards and a waterfront promenade that establishes the Griffins’ formal geometry for the lake edge. Those opposed to the scheme argue that the project is unsympathetic to the significance of the picturesque parkland setting intended for the lake; pervasive themes that were espoused by the then National Capital Development Commission, not long after the implementation of Parkes Way.

Electing not to go into battle over the objectors’ selective appropriation of what is significant, Irwin and Thalis took an approach to the waterfront park that drew on the Griffin Plan’s geometry, the geological intricacies of the basin and links to the broader landscape. As Irwin says, “the key to developing the project was to understand the underlying geology; the soils and the vegetation systems that could be supported.” The West Basin waterfront has the potential, through the application of these principles, to realise Griffin’s intent for a diversity of landscape experiences around the lake that included urban areas, while retaining the lake’s connections to Canberra’s landscape setting. Their focus and commitment on establishing a landscape system that is of the place, its microclimate and ecology should placate those concerned, however, time will tell.

Constitution Avenue, on the other hand, was the Griffins’ market street and the base to the National Triangle. For some time the avenue has been considered by many to be the most barren main street of any city or town in Australia, despite numerous, valiant studies and master plans attempting to kick-start the boulevard back into life, after the advent of William Holford’s Parkes Way.

Again the NCA’s Griffin Legacy project helped catalyse the political will and subsequent funding to make Constitution Avenue a priority, recasting the National Triangle as a human centred landscape. While the avenue has not been as controversial for Irwin and Thalis, it has nevertheless been technically challenging. As Thalis notes, “The geometry is very precise, the setbacks, the road alignment and in particular, the centre line needed to be carefully modelled to achieve what is essentially a design-led scheme.” The brief required the team to accommodate pedestrian friendly, but orthodox traffic structure, while allowing space for a potential light rail corridor.

Irwin and Thalis are the first to acknowledge that the project was a major team effort from both JILA and Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, while also acknowledging the extensive contribution of the client and consultant team that curated the redevelopment of Constitution Avenue. As such it is a collaborative success that has vanquished the long-deceased traffic engineering orthodoxy of Parkes Way. Testament to this shift in attitude has seen the western end of Constitution Avenue, finally breaching the Vernon Circle roundabout to complete the city apex of the National Triangle.

Similarly, Campbell Section 5 and Hassett Park, bounded by Anzac Parade and Constitution Avenue, are the result of rigorous research and deference to the inherent natural qualities of the site and its urban context. “Griffin’s views are controlled and framed,” says Irwin. “They visually create the landscape setting through very specific tropes and layers”. The urban planning of this project and the relationship between the architecture and landscape architecture, epitomise why most planners and design professionals praise Canberra: the symbiotic relationship between the urban structure and the city’s landscape setting.

An urban stream that structures Hassett Park.

Village green, connecting new and existing residential areas at the north end of Hassett Park.

Aerial view of Campbell Section 5

So just how does landscape architecture negotiate ‘significance’ in approaching and negotiating landscape architectural design in Canberra? “There are many interpretations of the Griffins’ and their landscape legacy, which are often contradictory and very entrenched,” says Irwin. “These are very difficult spaces to negotiate.” These resulting projects are like a well-conceived thesis: the product of a rigorously applied method, a commitment to process and with a hint of creative genius.

Delving into the nuanced and respectful tactics deployed by Irwin and Thalis in Canberra, there is a limit to how much can be achieved in these few passages. However, valuable insights can be drawn from their approach. As Irwin modestly notes, “we are not trying to leave our mark on Canberra. These projects have their own legacy of plans, policies, schemes, champions and protagonists.” Irwin and Thalis don’t careen down the Hume to dictate their views, but rather, commit to detailed research and developing a deep understanding of the significant contributions made by many to Canberra, stretching back to the Griffins.

Irwin concludes, “Canberra has its own strength in the landscape that cannot be unmade, however the city should celebrate its significance and be careful to avoid trying to be something it is not.” In the end their pragmatic and intelligent approach to landscape architecture in Canberra has produced works that are befitting the landscape reputation bestowed on the nation’s capital. And this makes their contribution to the city, significant.

—

Dr Andrew R MacKenzie is a Registered Landscape Architect and academic. His research interests include open space management, governance and planning issues related to urban landscapes. Andrew is currently working and researching in Vanuatu.

Gay Williamson is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects and adjunct at the University of Canberra. Gay has had over 30 years experience in private, government and academic spheres.

[This article was modified from the original on 29 November 2017, to include the names of additional collaborative team members]