K2K: Addressing the growing pains of the middle suburb

The K2K Urban Design Competition was more than a competition to upgrade a congested piece of Sydney’s Anzac Parade in need of rejuvenation. It was a competition to reimagine our middle suburbs.

Drive about 10 minutes from most Australian city centres and you’ll find our middle suburbs. Since they were first established about a century ago, some have faired pretty well. Others not so well. In either case, these middle suburbs are now under pressure from multiple fronts. An environment of intense speculation, combined with real housing need, means state government demands that local councils pull their ‘population growth’ weight. This in turn means providing additional amenity to help swallow the bitter pill of building height increases. More amenity, more people, more traffic, in an environment where change is often robustly resisted by a vocal and digitally mobilized residents’ association. This is the context in which the K2K Urban Design Competition was conducted.

Prior to the competition there were a variety of more specific drivers. Randwick City Council (RCC) had received a number of inappropriately large apartment development applications, which were not approved, but council recognized that the ‘problem’ of population growth would not go away. This much is clear within the Sydney Plan for Growing Sydney, which identified a number of locations (including a large section of Anzac Parade) deemed areas ripe for ‘urban renewal opportunities’ (read: more homes). The ideas generated by the K2K competition were therefore intended to assist council in responding to Sydney’s bigger plans, and to help it generate a comprehensive planning strategy for the Kensington and Kingsford Town Centres. This strategy will ‘set out the preferred directions for how sustainable growth and urban renewal will be managed in the years to come’.

K2K is therefore a rare thing: a process of exploring innovative design opportunities for a large urban area, prior to a local government planning strategy. Design-led planning, as opposed to inviting design contributions after the key structural decisions have been made. As the NSW Government’s Department of Planning and Environment puts it, ‘Design-led planning is more important than ever as we work to increase housing supply‘.

Whether or not RCC makes full use of the outcomes of K2K is yet to be seen. At the point of writing, the comprehensive planning strategy is still being written. Meanwhile, it might all be undone by the imminent amalgamation of RCC into the much larger Eastern Beaches Council. Regardless, a number of key themes emerged across all of the competition submissions. Foreground examines all four submissions to reveal ideas that could unlock answers to the ‘troubled middle-suburb’.

It’s not a local problem – it’s a network problem

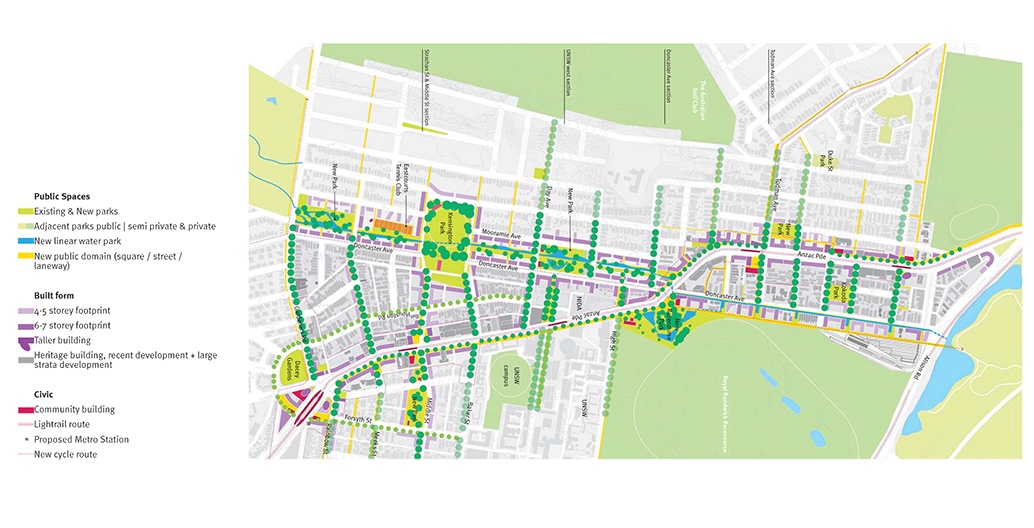

All four submissions exceeded the site limits of the competition, illustrating that you cannot draw a hard line around a community. You cannot propose design solutions for one bit of a locality within a boundary, while ignoring everything else. Communities and localities are interconnected within a region, and problems with transport, traffic, community resourcing and natural amenities need an integrated approach.

View of Future Parade submission, including proposed community library

CODA Studio's water park, part of a flooding strategy

Embracing the local university, by ASPECT Studios, SJB, Terroir, SGS.

A new life for Anzac Parade, by JMD Design, Hill Thalis + Bennett and Trimble

Avoid urban valleys

A key design proposition shared by most of the competitors was to reverse the trend of loading Anzac Parade up with all the height and population increase, in order to avoid battles with residents off the main street. While that may be easier in the short term, it makes it harder to turn Anzac Parade into anything but a valley of cars, with increased noise, more ‘superblocks’, less cross circulation and increased concentration of parking, much of which will sit above ground, deadening all around it. K2K offers a number of solutions for how to spread medium density across a wider area, to the east and west, locating new medium level apartments immediately adjacent to new parks. A core proposition of the winning submission proposes to directly link increased density to increased amenity.

Trees are good, duh

Bring back nature to the city. This can be done through large scale initiatives such as the uncovering of a sealed underground waterway, to recreate the natural linear watercourse that was there before settlement, immediately creating major new public amenity. It can also be done incrementally, through investing in a sequence of small pocket parks, often repurposing otherwise residual pieces of public urban land, currently left to literally collect dust. In the context of Randwick, a major question to ask is why a huge open park of public land is locked off from public use. Yet that is exactly what the Randwick Racecourse is. Several competitors proposed the opening up of the racecourse on its fringes, to improve the public’s access to nature.

A third pipe

All competitors proposed sustainable technology initiatives, with plans to localise energy creation and water treatment. Plans to provide recycled water ‘third’ pipes, connected to large-scale water harvesting, and the similar servicing for neighbourhood electricity generation, are a natural progression from small-scale residential efforts. Exploiting the community’s economy of scale allows for significantly more efficient investment, particularly when planning increased densities delivered through multi-residential developments. How such services are implemented can bring challenges, requiring careful consideration in the context of ripping up roads and meddling with existing services. Some would say that such thinking would have been best conducted prior to the current light rail major works, but that would require The Department of Transport to talk to The Department of Planning and Environment once in a while. Nevertheless, K2K makes a clear case that we are now beyond the token installation of solar panels on council offices. It’s time to think sustainability as a community-wide responsibility.

Planning can be creative too

Several submissions specifically proposed the use of innovative planning provisions such as the exclusion of certain preferred uses from Floor Space Ratio (FSR) calculations. Council could set priority businesses, such as tech start-ups, community services and other valuable assets for the community, and give developers incentives to include these as specific tenancies within a development, on the second floor for instance. More simply, proposals included a recommendation that council strategically considers the nature of ‘value uplift’ as a consequence of planning changes, and use this value as a bargaining chip, when negotiating better development outcomes.

Break down the university silos

Universities contribute significantly to any knowledge-based economy, and Australia is no exception to that rule. However, we tend to underestimate how much our universities, dotted as they are all over our cities, can contribute to the streetscape and the local community. The presence of UNSW along Anzac Parade provides a case study in how to build bridges between the fabric of the city, and that of the campus.

Foreground commends all four competitors for their inspiring reimagining of Kensington and Kingsford, and by extension, all those other middle suburbs across Australia undergoing the same growing pains.

Winner:

JMD, Hill Thalis + Bennett and Trimble

Team Comprising: James Mather Delaney Design Landscape Architects, Hill Thalis Architecture and Urban Projects, Bennett and Trimble Architecture and Urban Projects

Other competitors

SJB, ASPECT Studios, Terroir, SGS

Team Comprising: ASPECT Studios Urban Design and Landscape Architecture, SJB Architects and Urban Design, SGS Economics and Planning, and Terroir Architecture and Urban Planning

CODA Studio

Team Comprising: CODA Architecture and Urban Design, Realm Studios Landscape Architecture, and GTA Transport consultants

Future Parade

Team Comprising: JBA Urban Design and Planning, Stewart Hollenstein Architecture and Urban Design, Arcadia Landscape Architecture, The Transport Planning People and Jess Scully