10 points of note about the late Dr John Friedmann

Renowned urban planner Dr John Friedmann has died aged 91. Foreground gives you a 10-point primer on Friedmann’s vast legacy if you aren’t already acquainted.

The influential urban planner, educator and writer Dr John Friedman has died aged 91. However, the legacy of this “Pope of Planning” will reverberate throughout the urban planning world, continuing to shape the face of our cities for decades to come.

Born in Vienna in 1926, Friedmann joined the European war exodus to the United States age 14 in 1940. He writes that he was “expelled” from Austria and remained “a perpetual traveller”. In spite of this, Friedmann has left a considerable legacy across the Americas, having taught in Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and at great length, in the US. Friedmann was the founding professor of Urban Planning at the University of California Los Angeles Graduate School of Architecture and Planning, and its head from 1969 and 1996. In 2001, he was made an honorary professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Community and Regional Planning (SCARP), where he remained prolific until his passing.

In Insurgencies and Revolutions, a recent monograph on his legacy, co-editor and Principal Fellow at the University of Melbourne’s School of Geography Haripriya Rangan notes:

“Every generation sees itself at the verge of a new social era, one that it is about to create. John Friedmann has envisioned and led the vanguard in creating several of these eras in planning, and has enjoyed the good fortune of a long life to see his students and colleagues forge new eras of their own”.

The author of 18 books and over 180 chapters, articles and reviews, he was one of the pioneering urban thinkers of the late 20th century. These works have been translated into multiple languages, and in 2006, he was the inaugural winner of the UN-Habitat Lecture Award for lifetime achievement in service of human settlements. A selection of this writing is available at his University of British Columbia profile page.

For those of you who are unacquainted with his work, here’s a recap of his legacy.

1.

He understood the inherent tensions within free-market cities.

“Although some varieties of socially rational planning aim at helping private business plan its own actions successfully, other varieties place severe restraints on market forces and some of them event substitute political decision-making (aided by planning) for the operation of the market.

Because planning in the public domain is politically inspired, it creates conflict. In a head-on collision with private capital, state action based on planning is likely to be successful only when it is supported by large-scale political mobilisation.”

From Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action (1987).

2.

He didn’t want urban planning to be an echo chamber.

“…I shall also assume that all planning must confront the meta-theoretical problem of how to make technical knowledge in planning effective in informing public actions. The major object of planning theory, I shall argue, is to solve this meta-theoretical problem. If it is not solved planners will end up talking only to themselves and eventually will become irrelevant”.

From Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to Action (1987).

3.

He was an early proponent of local and regional planning, in contrast to the heavy hand of federal top-down planning traditions.

“We need to privilege regional and local over national and transnational space. This leads to a decentered view of planning. I am not saying that national and transnational planning is obsolete… The problems and conditions of planning are not everywhere the same, and it is the specificities of place that should be our guide”.

Taken from ‘Toward a Non-Euclidian Mode of Planning’, published via the Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol 59, Issue 04 (1993).

4.

He looked to Chinese philosophy when thinking about planning approaches:

“I confess a weakness for Chinese philosophy. Indeed, in my book on transactive planning, I included a short section entitled ‘The Tao of Transactive Planning’. Some critics contemptuously dismissed this as a modish conceit from La-la land (I was living in Los Angeles at the time). But I was serious.

In Daoist beliefs, the cosmos is in constant movement, pervaded by two energy flows (qi), which together constitute a unity of opposites. In contrast to western thinking, which obliges one to choose between two opposing propositions (“they cannot both be true”), and in which dialectics takes the form of a confrontation, Chinese tradition holds that opposites, though in principle needing to be harmonized, are nonetheless in a continual state of tension: the yin force (which also contains some of its opposite energy) and the yang force (which likewise contains elements of yin) – neither force being entirely “pure” so that transformation is an ever-present possibility– alternate in their relative strength. The Chinese Book of Changes (I Ching) traces these dynamics via an ingenious system of 64 hexagrams. In this constant play of energies, no situation ever remains the same but is undergoing often-subtle changes favouring one force over another.

I believe that this metaphysics has a great deal of explanatory power, especially when studying Chinese historical experience. But I believe it to be useful also in the western world where we are more accustomed to think in terms of either/or rather than both/and. It is particularly applicable in planning conflicts. I don’t want to draw too sharp a distinction between western and Chinese ways of thinking and acting, because clearly we who live in the West also know how to negotiate and compromise in order to move forward. But the yinyang dialectics is a built-in characteristic of many Chinese institutions and practices in ways that they are not in our world.”

Taken from ‘Towards an Intellectual Biography’ published in Encounters in Planning Thought: 16 autobiographical essays in spatial planning (2017).

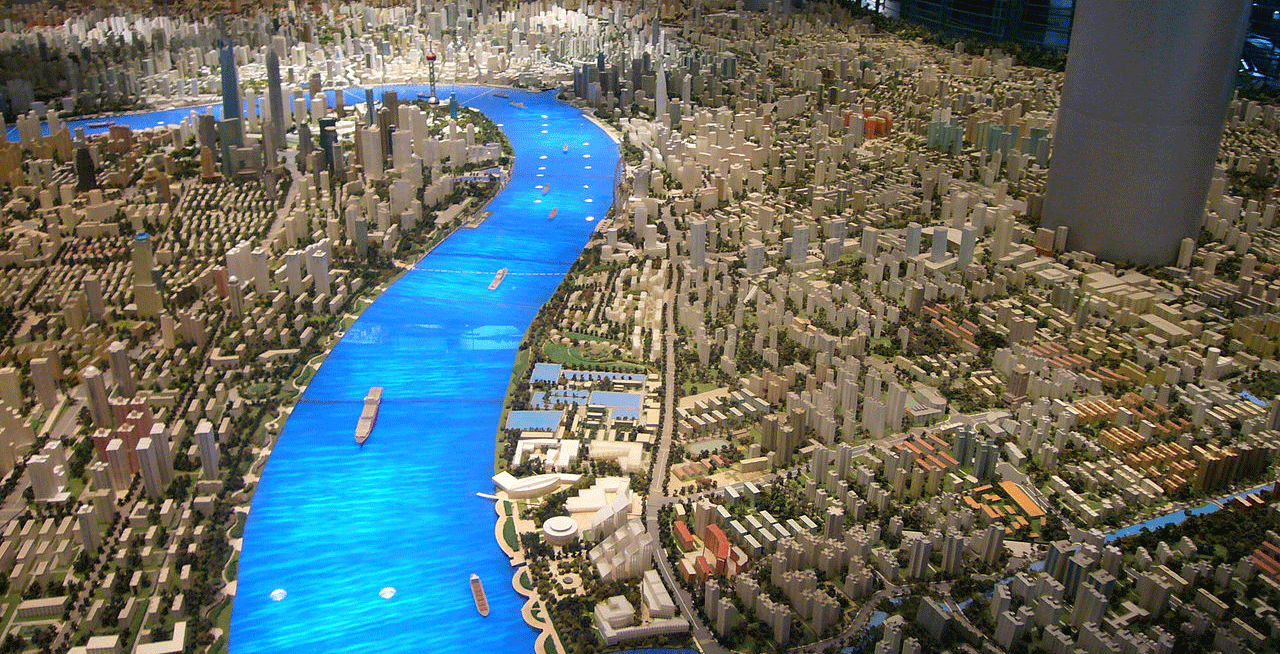

Shanghai's dense urban centre.

Shanghai at night. Image: Mstyslav Chernov via Wikimedia Commons

Overlooking Shanghai's Century Park. Image: Mgmoscatello via Wikimedia Commons

A model of Shanghai at 2020. Image: Urban Planning Exhibition Centre.

5.

The western experience of market-led modernisation isn’t necessarily going to be repeated.

“As many have observed, there is something quite unique in what is happening in today’s China, though how that uniqueness is constituted is often difficult to say. Despite superficial similarities, China’s modernisation is not simply replicating what has already occurred in other countries, whether Japan or the US. It is rather a process with distinctive characteristics and results on the ground that the closer you study them, the more you realise their uniqueness. But how are these specificities to be identified and even more, interpreted?

We have yet to undertake comparative research that looks at Russia, Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, India, or Brazil, comparisons that would help us better to understand the specific differences in a modernisation that in the current perspective is too often amalgamated with the homogenisation of global markets”.

Taken from ‘Four Theses in the study of China’s urbansation’ published via the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol 30, Issue 02 (2006).

6.

But China’s development also teaches us what not to do.

“In the half century since Henry Churchill and Jane Jacobs, the world’s great cities have undergone a sea change. Nearly four billion people, more than half the world’s population, are now living in cities, and we are in the midst of what must surely count as one of the great city-building epochs in human history. Most of the new cities are rising in Asia, especially China. As a result, China now has some 20,000 city planners. Some of them are officials staffing municipal planning bureaux, others are professionals skilled in drawing up physical plans. All around them, building after building is rising skyward, and as the city’s grid pushes ever outwards from the centre gobbling up precious farm land and countless villages, planners have a hard time staying abreast of the actual changes that are happening on the ground.

Trained in schools of architecture, planners understand the city chiefly as its buildings and expressways, people don’t usually appear in their drawings. Their plans are typically on a scale that renders neighbourhoods – the living heart of the city – invisible. Physical plans, in China and wherever else planning is practiced, are two-dimensional constructs, so that people don’t show up at all, or if they do, are swept up into aggregate population statistics: so many people in 2000, so many more in 2010, while failing to count all those without the ‘right to the city’ – that Henri Lefebvre, the great French urbanist and philosopher, argued is a right that all of us should claim – because in China, they are merely listed as transients, temporary workers and their families who, although they have come to work in the city, are not permitted to lay claim to it.”

Taken from ‘Place and Place-Making in Cities: A Global Perspective’, published via Planning Theory and Practice, Vol 11, Issue 02 (2010).

A protest during Hong Kong's 2014 'Umbrella Revolution'. Image: Studio Incendo via Flickr

A protest during Hong Kong's 2014 'Umbrella Revolution'. Image: Studio Incendo via Flickr

A protest during Taiwan's 2014 Sunflower Movement. Image: tenz1225 via Wikimedia Commons

7.

Global peri-urban spaces create both concrete and abstract effects.

“How literate are these populations, distinguishing younger from older residents, men from women? Do they have access to electronic communication devices? Do they commute to central cities or other already industrialised zones located in the peri-urban? Do they have social contacts across the spread of the urban? Do they watch television? And how do all of these impact thought patterns, knowledge, aspirations, and behaviour?

The mental horizon of peri-urban populations is continually expanding, and along with this produces a new awareness of one’s place in the world of opportunities, dangers, and risks that we inhabit, along with cultural changes in individual attitudes and conduct that occur at seemingly hyper-rapid speed.”

Taken from ‘The Future of Peri-Urban Research’, published in Cities (2016).

8.

Urban planning is a lot more than the urban grid. The urban planner bares witness to the changing social mores of the populace that a grid serves.

“Closely related is the cultural dimension of everyday life. Here the urbanist is likely to look for the emerging patterns of youth culture, changing fashions in popular music, new forms of leisure activity such as skateboarding, gender relations, novel forms of behaviour such as showing affection in public, radio hotlines from suicides to sex, and new forms of consumer behaviour, all of them, in one form or another, displaying the hybridity of the contemporary city.”

Taken from ‘Four Theses in the study of China’s urbansation’ published via the International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol 30, Issue 02 (2006).

9.

He didn’t care much for the myriad of ways we can spin ‘displacement’.

“Dis/placement is one of the most common phenomena in modern city life. We often use other words to talk about it – people removal, squatter eradication, slum clearance, gentrification, rehousing, redevelopment – some terms more benign, others more brutal, but the results in the end are roughly the same.”

Taken from ‘Place and Place-Making in Cities: A Global Perspective’, published via Planning Theory and Practice, Vol 11, Issue 02 (2010)

10.

He wants you to talk to your neighbours:

“Contrary to command planning, which globally speaking is still the dominant form, I would argue that planners need to engage neighbours directly, and that this engagement means to establish a moral relation that from the start acknowledges people’s ‘right to the city’, which is to say, their right to citizenship.

My values for making good neighbourhoods include ensuring a livelihood for its residents, safety for families and children, ease of social interaction, convenient, cheap, and rapid access to the city, welcoming to newcomers, acknowledging difference, fairness in the distribution of public goods, and ecological sustainability. It is a tall agenda.”

Taken from ‘Place and Place-Making in Cities: A Global Perspective’, published via Planning Theory and Practice, Vol 11, Issue 02 (2010).

––

Vale Dr John Friedmann (1926 – 2017)