A stroll down the street of tomorrow

An upcoming installation in Sydney will give visitors firsthand experience of where our cities might be heading in the future.

What makes for a good street? For Chris Isles, executive director of planning at Place Design Group, it’s simple. “A good street is a place that prioritises people over cars,” he says.

Isles is leading the design team on a forthcoming installation in Sydney’s CBD called “The Future Street”, which will feature as part of the 2017 International Festival of Landscape Architecture. A kind of urban version of the display home, The Future Street will give the public an opportunity to experience firsthand the effects that emerging technologies might have on how we design and use one of our most important public spaces.

The car, of course, was once an emerging technology itself, and its widespread uptake would go on to have dramatic and unexpected effects on the quality of our streets. Space-hungry and infrastructure intensive, cars brought with them swaths of bitumen-coated roads and carparks that turned many of our city streets into what Isles refers to as “traffic sewers”: hard-scaped environments designed primarily to accommodate machines, the antithesis of people-friendly places.

Ironically, its changes in automobile technology that Isles believes could now be making more people-friendly streets and cities a reality.

“That might be possible when we start heading into autonomous vehicle territory because in theory we’ll need less of them, if they’re shared and connected,” he says. “Once we kick cars out of streets, or have less reliance on them thanks to autonomous vehicles, we can reclaim bitumen spaces for a range of different things, whether that’s for gardens, or urban agriculture or just for us as people.”

Autonomous vehicles are part of a wave of new “smart” technology that some experts see as an emerging “Internet of Things”, wherein everyday objects are all wired to communicate with the cloud and potentially one another. To deliver The Future Street, the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA) has partnered with both the Internet of Things Alliance Australia (IOTAA) and the Smart Cities Council Australia New Zealand. While some have envisioned this burgeoning future in terms of enhanced consumer convenience – refrigerators that let your local supermarket know when you’re out of milk, or cars that tell your house to switch the lights on when you’re on your way home – these organisations believe it will have a much more dramatic impact on the way our cities function.

“Our streets are going to be ground zero for the ‘internet of things’,” says Adam Beck, Executive Director of the Smart Cities Council of Australia and New Zealand (SCCANZ). “It’s a provocation more than anything. We’re laying the challenge now that we can reimagine our streets to be something more highly productive that gives back to people.”

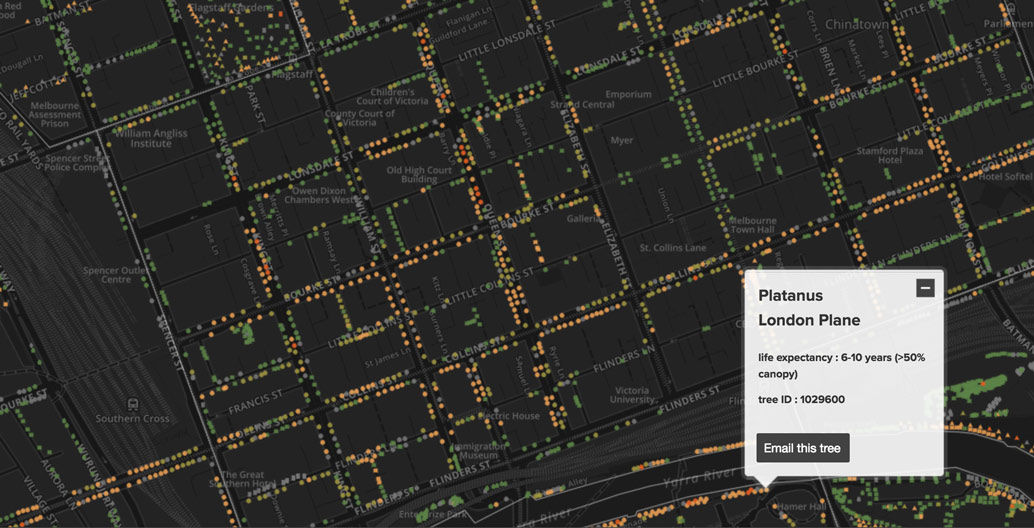

The City of Melbourne's Urban Forest Visual, mapping near 60,000 trees in the municipality.

The street of the future could have fewer cars, less bitumen and more green space. Image: Place Design Group

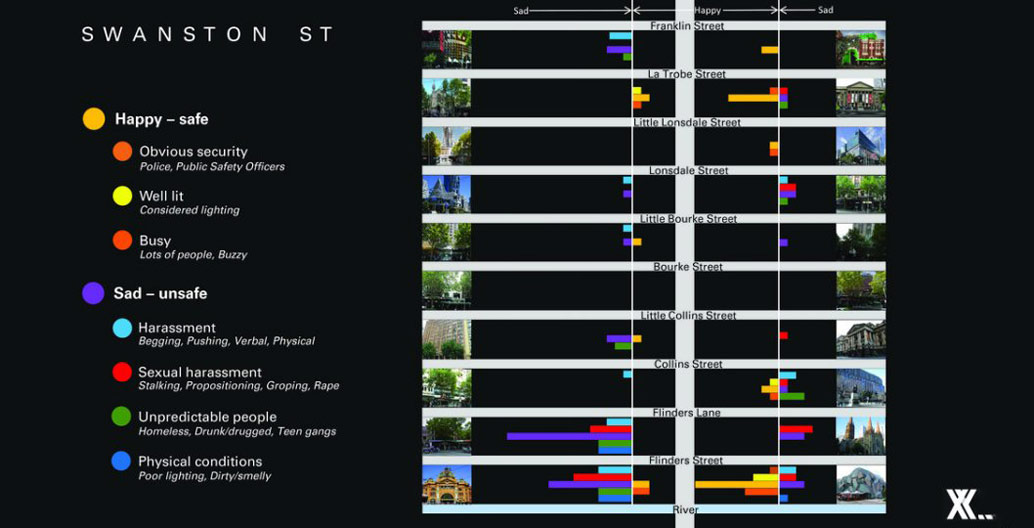

XXYX Lab's ‘Free to Be’ map, a collation of anonymous data mapping female experience with the Melbourne CBD.

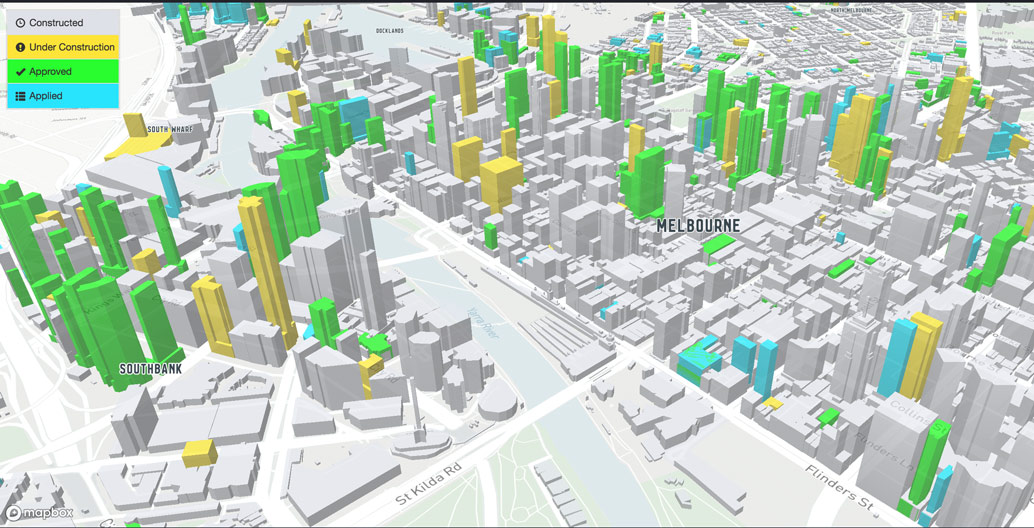

The City of Melbourne's Development Model Index.

Now we traverse a city in two dimensions: physical and virtual space. From programmers using Instagram’s aggregate data to create locals city guides, to how Google maps your movements around a city, planners, urbanists and landscape architects could have as much of a role to play as their peers in technology.

Floating around are notions of ‘green infrastructure’, big data, and diverse mobility – and there’s more to this than autonomous vehicles. “The internet of things is an amazing economic, social and environmental opportunity,” says Beck. “Street sensors are able to capture tracts of data in real time that gives us a sense of what’s going on in our cities.”

Over recent years, the City of Melbourne has been working on capturing data that provides citizens with information in real time. Its urban forest visual, for instance, shows the relative health, species and life expectancy of all 60,000+ trees in the municipality (and you can email them, too). For planning nerds, there’s the Melbourne Development Activity Model, giving users a 3D visual of buildings applying for a construction permit, those approved, and those under construction.

“A ‘smart city architect’ is the language we’re starting to use now, because it’s a new kind of profession in a new kind of space which is in the middle of the challenge of bringing these things together,” says Isles. “Part of the challenge is around aesthetics and how it looks physically, but then there’s a whole new layer of technology that sits on top – how do we ultimately deliver these things in a symbiotic manner and sympathetic way so that the street doesn’t feel like it’s bristling with technology?”

In a lot of ways, the installation that Isles and the rest of the Future Street team are planning won’t be explicitly about high technology at all, but about ideas like shared mobility, where there is a mix of transport modes, from walking, to bikes and autonomous buses (the installation will feature one of the few autonomous shuttle buses in Australia) and street activation. “So rather than streets being just places you move through, they’re places you want to hang out in,” says Isles “It’s the concept of ‘sticky streets’, where there are lots of reasons for you stay in the street and support businesses.”

The team is also hoping to install some elements that talk to the potential of urban agriculture – beehives, a grove of fruit trees and some more traditional kitchen gardens, albeit installed vertically to demonstrate that food production doesn’t have to consume acres of precious urban space.

While the installation might not be bristling with tech, though, that’s not to say it won’t feature prominently. A raft of sensors will be monitoring the street, all of which will feed data back to a central dashboard that displays everything from its water and power usage, to its air temperature and quality. There are also plans to use thermal cameras to show how plantings and vegetation affect urban heat gain.

Ultimately, The Future Street will aim to demonstrate to visitors in a very literal way what our streets might be capable of with smart technology embedded in their design DNA.

“Those in the built environment will have to become the new data scientists,” says Beck. “They lie at the intersection of the physical and digital worlds, and to me, they’re in a perfect place, because they’re going to orchestrate how we blend technology with the landscape by asking the right questions.”

—

The Future Street will be presented at the International Festival of Landscape Architecture from October 9-15, 2017.