The water is coming for Copenhagen; good design could be its best defence

The Danish capital is associated with fables, vikings and in recent decades, good design. As Copenhagen city prepares for a century of extreme climate events, landscape architects, planners and inhabitants are finding creative solutions that provide not just flood defence, but more urban amenity.

Each day, hundreds of thousands of commuters snake their way across bridges that connect Copenhagen’s many islands. Cyclists, motorists and pedestrians speed over busy canals and race through the thin cobbled streets of the old city, while canal tour boats filled with tourists slowly orbit the centre. On a warm day, the canals are lined with sunbathers jumping from BIG architects’ famous harbour baths, with their distinctive barbershop stripes. Paper Island, in the Christianshavn district, is home to the city’s new pop-up cultural precinct. It is regularly filled with diners, who spill out of the warehouse housing Copenhagen Street Food to watch the sunsets on its banks.

Since its beginnings as a Viking fishing village, Copenhagen’s relationship with the Baltic Sea has played a vital role in shaping the city’s culture. Today, canals cordon off its many islands, serving the veins that pump life into its distinct geographical and cultural pockets, such as Christianshavn, even as they divide them. The canals contribute both to Copenhagen’s particular aesthetic and its leading place in global liveability rankings. But the harbour city, whose name has become shorthand for the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference, sees water not only as its biggest asset, but one of its biggest risks.

On 2 July 2011, Copenhagen was inundated with 150mm of rainfall in just three hours. The severe storm caused endless chaos, flooding train tracks in Copenhagen’s central station, damaging countless historic facades and forcing the evacuation of public buildings. Overflowing sewerage systems, electricity outages and an estimated 5 billion Danish Kroner (AUD$1.03bn) in damage was a foretaste of the 21st-century’s predicted extreme weather events.

By the end of this century, it’s predicted that Copenhagen will experience 25-55 percent more precipitation in winter months, while the city’s typically wet summer months will see up to a 40 percent reduction in rainfall. Light showers will be replaced by heavy downpours, putting pressure on the city’s ability to deal with deluges. Floods pose a serious threat to those living in the city, with 61 percent of residents having already experienced water damage to their properties. While rainfall poses a threat from above, rising sea levels threaten the city’s inner islands, which could easily be damaged by flooding if canals overflow.

Copenhagen’s unique topography means that the city is already feeling the the impacts of climate change more rapidly, and more acutely than many cities around the globe. But while the future might seem dire for the city given these predictions, Copenhagen is looking ahead with confidence. City planners have already begun work on creative landscape architecture solutions that not only respond to the climate threats, but proactively engineer new landscapes for residents.

The Islands Brygge Harbour Bath spans 1.6m², completed in 2002.

Copenhagen residents enjoy the Islands Brygge Harbour Bath, designed by BIG and JDS Architects.

The capital's landmarks, such as the ‘Black Diamond’ sit just above a changing water levels.

The Royal Playhouse of Denmark is vulnerable, too.

Copenhagen's old town, like Venice, wasn't built for the storm surges predicted by 2100. Image: Georg Bräunig.

Transforming Copenhagen’s landscape to suit a changing climate

Copenhagen’s Climate Adaptation Plan, completed in 2011, identifies water – in the form of rainfall and flooding – as key threats. The plan places landscape architecture at the core of planned upgrades to existing areas and the development of new ones. Lykke Leonardsen, the City of Copenhagen’s Head of Resilient and Sustainable City Solutions, sees the city’s climate adaptation as an opportunity to develop new urban assets and experiences for its inhabitants. “How can we create added value from a problem?” asks Leonardsen, who is passionate about ensuring that Copenhagen is “not only solving the problem of water management, but actually seizing the opportunity to upgrade the neighbourhood.”

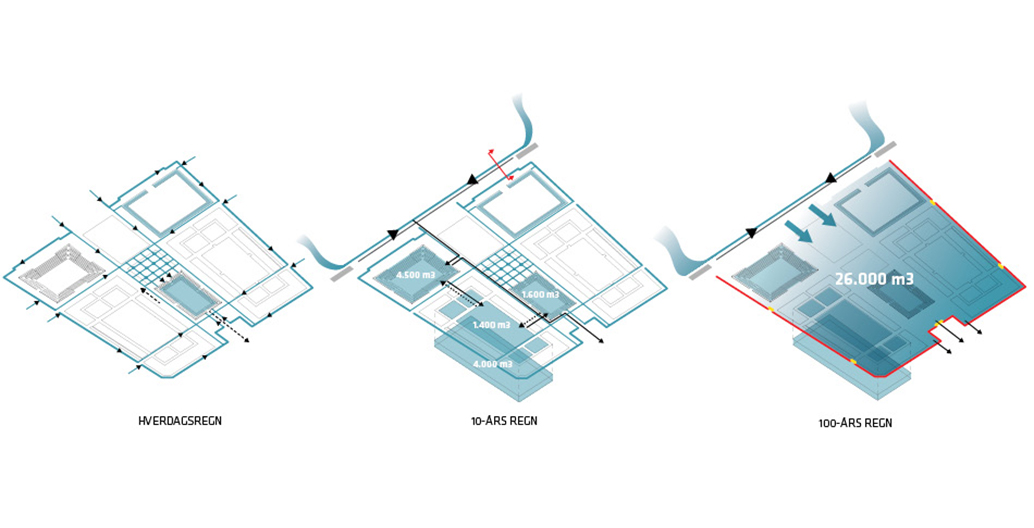

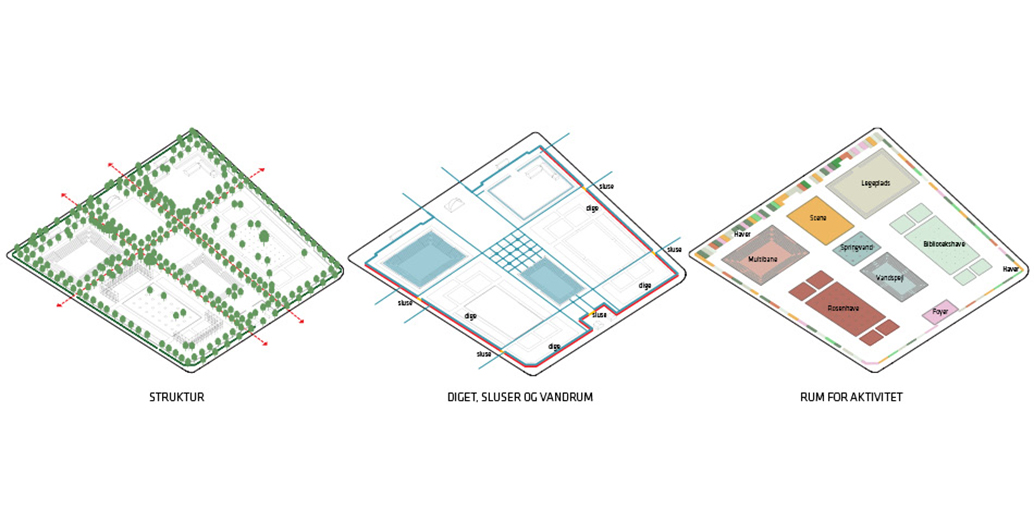

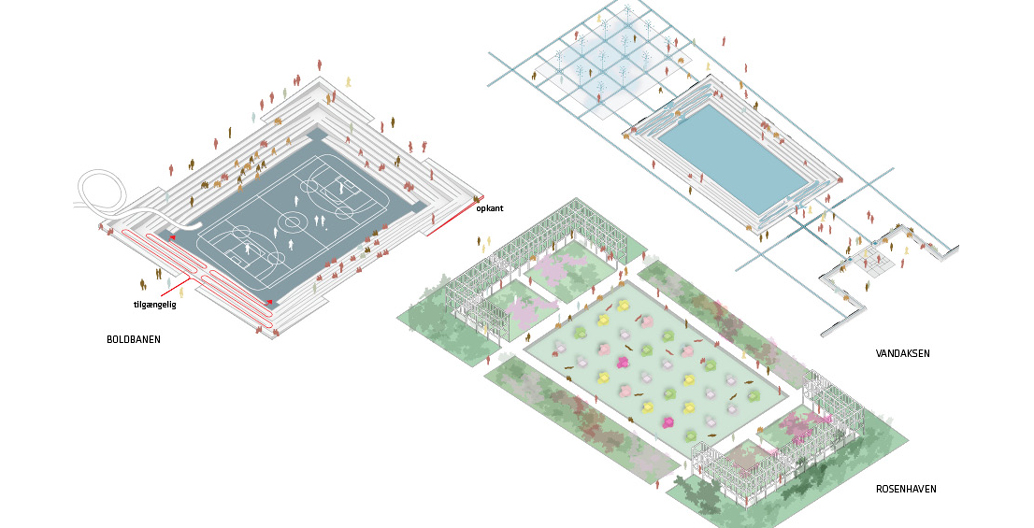

Leonardsen believes that the cultural integrity of an area should not only be maintained, but enriched through adaptation strategies. “We look at the specific landscape architectural characteristics of the area and find out what we want to keep, what we want to strengthen further, and what opportunities there are to bring something new to the space,” she explains. Leonardsen points to a forthcoming park in Vesterbro, her neighbourhood, by way of an example. The gentrified suburb, home to buzzing restaurants, galleries and nightclubs, will see one of its local parks transformed into a flood-proof public space. Enghaveparken, previously a large green space in the heart of Vesterbro, is currently being redesigned to house a mixed-use sports and recreation area. It will feature a sunken ball court surrounded by sloped seating that conceals a large retention wall. The park’s design will allow the facility to store up to 24,000 cubic metres of water in the event of cloudbursts – sudden, extreme levels of rainfall. It’s expected that major weather events will see the ball court fill up entirely every few years, turning the sports facility into an ephemeral pond that will drain out over a 24 hour period. In the meantime, though, Leonardsen is excited that residents like herself “will get a whole new park for the area.”

The park boundary serves as a dyke, retaining water to be filtered around the grounds and community gardens.

Lykke Leonardsen, City of Copenhagen’s Head of Resilient and Sustainable City Solutions. Image: CPH CC.

Enghaveparken ballpark in Copenhagen rendered during flood. Image: Tredje Natur Cowi and Platant.

Enghaveparken ballpark rendered during a dry period. Image: Tredje Natur, Cowi, and Platant.

The site falls by 1m to create a ‘dustpan’ of 200x200m holding 14.500 m³ of water. Image: Tredje Natur.

The three modes of programming for the park. Image: Tredje Natur.

The park at the surface level. Image: Tredje Natur.

The park will be able to collect 26,000 m³ of water. Image: Tredje Natur, Cowi, and Platant.

The park has been functioning since 1928. Image: Tredje Natur, Cowi, and Platant.

Stormwater from cloudbursts can overwhelm the city’s aging sewerage system, which risks contaminated water flowing back into the harbour and erasing decades of deliberate work to bring Copenhagen’s once-polluted harbour to a level of cleanliness that makes it fit for both swimming and the harvest of local oysters. One response to this problem has been the creation of Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) in the form of bumps, embankments, ditches and kerbs which can help to redirect water into areas where it causes least damage, such as sportsgrounds, parks and open spaces. Another design response is the creation of cloudburst ‘fingers’ – a network of key roads – which have been identified as channels to convey runoff into underground reservoirs that act as safety valves, thereby reducing flooding in low-lying areas.

These strategies have helped put Copenhagen’s Climate Adaptation Plan in motion. As the city tests their effectiveness, Leonardsen’s primary focus is leading an international engagement programme that spreads learnings from the Danish city around the world. Despite their successes so far, Copenhagen’s planners know that their journey is just beginning, and there is plenty more to be learned. “There are lots of places where you can go cherrypicking, and bring new strategies back home”, says Leonardsen, who looks to Seattle, Singapore, Rotterdam and London for inspiration. “We have in many ways outrun international cities when it comes to climate adaptation, but we are always looking for new ideas.”

Landscape architecture for a harsher future

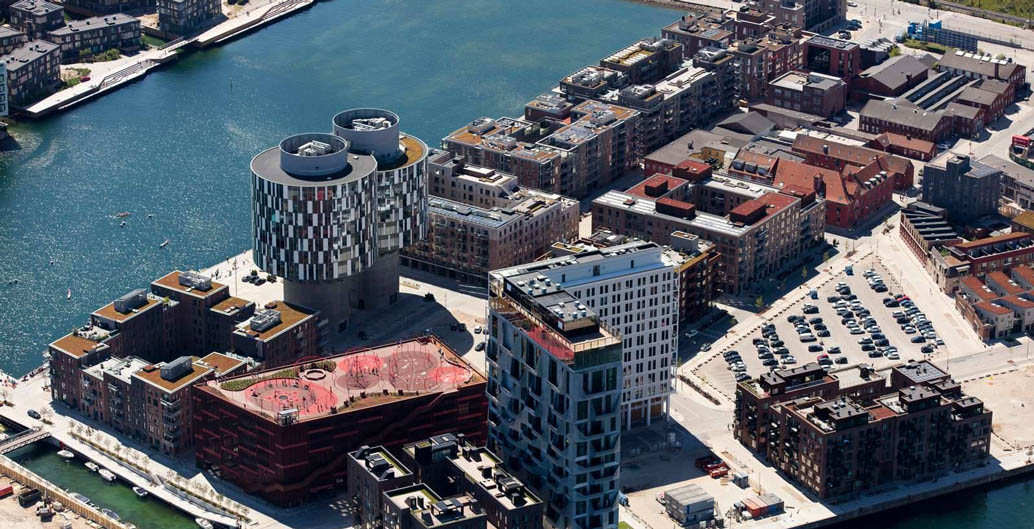

After 2050, cloudbursts will no longer be Copenhagen’s main concern – instead, the city’s greatest threat will come from flooding from the sea. Copenhagen is implementing dramatic landscape transformations to prepare for rising sea levels (the global total to be predicted as high as 2.7m by 2100), many of which can be found in new developments built to withstand the harsher climates of the future. Nordhavn, a new business and residential region built upon reclaimed land in the city’s North Harbour, is deliberately elevated through soil deposits taken from the construction of new Metro lines in the city centre. Despite its height, the area will likely require an additional dike for protection from high tides in the decades to come (coastlines around Europe are set to rise between 57-33cm by 2100). The Øresund coastline at the south of the city is facing similar challenges, and will need to be raised entirely to prevent flooding through the island of Amager (areas south of Copenhagen were inundated by storm surges measuring 1.57 metres during floods in 2017). Re-designing and rebuilding these areas will be necessary, as the capacity of watercourses to discharge water from flooded areas will not be enough to protect them. Such dramatic changes, the Climate Adaptation Plan argues, are likely to alter the North and South habours’ existing architecture and may limit recreational activity, yet this considerable challenge could well lend itself to further opportunities to improve urban amenity.

Stig Andersson, landscape architect and founding partner of SLA Architects, argues that the development of dikes and flood protection areas should be viewed through the lens of resilience, instead of sustainability. “Sustainability is normally maintained through built defense systems that protect man-made environments against natural incidents, which are perceived as attacks,” says Andersson. “Damaged and destroyed facilities are restored to the status quo, back to how they were before the ‘attack’ with the aim of erasing all traces of devastation and change, and of erasing all signs pointing to the city’s physical weaknesses.” Andersson invites landscape architects to focus on enhancing the amenity and utility value of their climate-response projects by focusing on resilience, adaptation and optimisation to explore new design possibilities.

The UN’s Copenhagen headquarters have set up in a eightpointed star tower, stretched over 45,000 m² on an artificial island off Marmormolen in Nordhavn. Image: CPH City & Port Development.

This approach can be seen in the design of Sluseholmen – a new development in Copenhagen’s protected southern harbour district that draws inspiration from the unique, colourful facades of Amsterdam’s Java Island. Once a network of silos, abandoned warehouses and junkyards, Sluseholmen is now a district of diverse commercial and residential buildings divided by an imperfect grid of canals. In line with the municipality’s guidelines for new developments, Sluseholmen’s buildings, bridges and walkways sit 2m above current water levels to ensure that they are protected from changing water levels and turbulent storms. However, given the predictions for the inner-city’s flood inundation, the area may withstand a minor rise in sea levels but would struggle with storm surges in the long-term. Sjoerd Soeters, one of the key brains behind the project, says “the open relationship with the sea will need to be closed… and the protection from the sea by dikes or sand dunes will be necessary”. Despite this assumed transition, designers have vowed to maintain pedestrian connections to the canals. Staircases dot the edge of the canal, leading pedestrians down to the water’s edge.

Sluseholmen is being built on a mixture of reclaimed land and new, human-made islands separated by thin canals. Image: PPHP

Sluseholmen will form part of a regeneration scheme accommodating 9000 homes. Image: Christoffer Grann.

Sluseholmen's revitalisation was completed in 2009. Image: Pleasant Places Happy People studio.

The canals are not merely a physical feature of the area; they play a crucial role in shaping social interactions in the neighbourhood. Sjoerd Soeters, the Dutch studio behind the design of the precinct, aimed to create an environment in which limited public space precipitated spontaneous social interactions, resulting in a sense of intimacy, safety and community. When walking along Sluseholmen’s canals, you can’t help but feel close and connected to the area and its inhabitants. Neighbouring Enghave Brygge also places sustainable landscape architecture at the heart of its community design. Like Sluseholmen, the community is being built on a mixture of reclaimed land and new, human-made islands separated by thin canals. A key characteristic of this development is the visible storage of rainwater. Rooftop rainwater collection is integrated into the design of residential buildings, which will allow residents to use recycled water for flushing toilets and in laundries. While most rainwater in the Enghave Brygge development will be stored in underground tanks, out of sight and out of mind, a number of climate adaptation features in the Enghave Brygge area are designed to be seen. Once completed, the ‘Water Square’ – a large amphitheatre structure connected to an underground tank – will double as a water storage facility, and a recreational area. The water level in the centre of the amphitheatre will visibly fluctuate, giving locals the ability to observe the way that changing weather shapes the physicality of what promises to be a popular meeting spot for residents and passers-by.

Building resilient communities around Copenhagen’s canals is key to securing a better future of the city. The implementation of sustainable landscape architecture in Nordhavn, Enghave Brygge, and Sluseholmen not only grants planners confidence in the city’s ability to adapt, but has given way to creative urban design solutions that will extend and enhance Copenhagen’s urban fabric for years to come.

Hans Tavsens Park can hold 18,000 cubic meters of ‘delayed volume’ at ground level. Image: SLA.

In the suburb of Korsgade, design practice SLA have proposed a year-round water garden. Image: SLA.

Proposal for another one of Copenhagen's water-sensitive parks, Hans Tavsens, after a heavy rain. Image: SLA.

New developments around the former ports of Copenhagen now dock budding kayakers instead of seafarers.

Will Nordhavn's open relationship with water be feasible in the long run?

The port authority will extend Nordhavn by 100 hectares over the next 20 years. Image: CPH City & Port Development.

Designing for a life with water

It’s not just urban planners and landscape architects who are rethinking the way that Copenhagen interacts with water. The presence of water between Copenhagen’s many islands is a major source of inspiration for the city’s creatives, who are eager to see if their brave new ideas can stay afloat. Many startups have converted houseboats into fully-functioning offices, and until 2015 Copenhagen’s canals were home to the floating kitchen of Noma’s ‘Nordic Food Lab’. Canals allow the city’s culture to spill across land-based boundaries and find new expressions on the water’s surface. In the summer, boats can roam freely between different neighbourhoods, while in winter, many will find a long-term mooring as the ice freezes around them.

Designing for canals, as opposed to around them has inspired unusual projects like BIG Architect’s ‘Urban Rigger’. The floating student accommodation is made from brightly coloured shipping containers stacked on top of each other, and moves to different locations in Copenhagen’s harbour. For Urban Rigger, water creates opportunities to challenge the idea of ‘home’ as something that’s connected to place, and puts into question the value of traditional urban landscapes, connected by familiar streets. So long as a suitable docking area can be found, the multi-storey microcosmic community – complete with green spaces, solar panels, and inner courtyard – can be relocated to a new community with ease.

Copenhagen faces considerable challenges in the face of climate change, but the city’s creative approach to climate adaptation has so far seen it embrace and enhance its unique urban characteristics. Copenhagen’s landscape architecture solutions to cloudbursts and flooding risks integrate with the physical and cultural fabric of the city, and create new assets to be enjoyed by its residents. They also allow for transformation that can adapt to new urban relationships to water – a useful foil in the looming new era of uncertain and unpredictable climate.

“The reason why we work with the grown environment when creating the cities of the future”, says SLA Architects’ Andersson, “is precisely because of its ability to adapt to change. That’s what makes nature’s processes so interesting and so potent in resilient urban development.”

Lykke Leonardsen will be speaking at Melbourne Design Week at the National Gallery of Victoria in March 2018.