The view from up here: changing visions for the Gold Coast

The Gold Coast’s tall buildings are integral to its cultural identity, but recent development threatens to undermine what makes the city unique.

Postcard images of Surfers Paradise in the early 1960s typically feature a lone giant: the ten storey Kinkabool in Hanlan Street, rising from a flat landscape surrounded by low-rise buildings. Around this time prevailing schools of thought advocated in favour of more tall buildings; as a way of introducing relief into the landscape, to take advantage of views to the surf, beach and river, and to create a distinctive urban form.

In a 1959 Gold Coast-focused edition of Architecture in Australia, Peter Kollar, lecturer in architecture at the University of New South Wales, argued that “the flat landscape at Surfers Paradise offers no topographical interest… There are no heights from where one could perceive the intricacies of the Nerang or proximity of the ocean.” In the same publication, John Hitch, an architect with the Queensland Government decried that “localised developments have all missed the possibilities of the proximity of sea to river, to create a dramatically developed locality, which might become its centre, symbolising the Gold Coast. Most cities have a symbol. There is nothing distinctive to the Gold Coast about surf and the beach, which are common to the whole of the Australian sea board!”

Fast forward more than 50 years and ask yourself how many tall buildings exist in this city today? In 2012, photographer John Gollings walked the length of the coast and captured every one of them. His count was around 650. Given the current rate of development, a good estimate is that there are more than 700 in 2018. It is not surprising then that the Gold Coast has become synonymous with tall buildings. Gold Coast towers are a particular breed. They are distinctly different, in style and form, from those found in other Australian cities.

Individually they are not particularly architecturally refined or innovative, but clustered together in the landscape they create a potent urban form and image. Perhaps this is why we are saturated with tourism images of long views taken from Point Danger or Mt Tamborine. It’s an image that easily misleads, creating the common misperception that together the Gold Coast’s tall buildings form a single spine of high-rise development, stretching the 40km length of the beach.

In reality, tall buildings have been confined through town planning regulations to a number of specific activity hubs: Southport, Main Beach, Surfers Paradise, Broadbeach and Coolangatta. In addition, there are small clusters at Runaway Bay, Burleigh and Palm Beach.

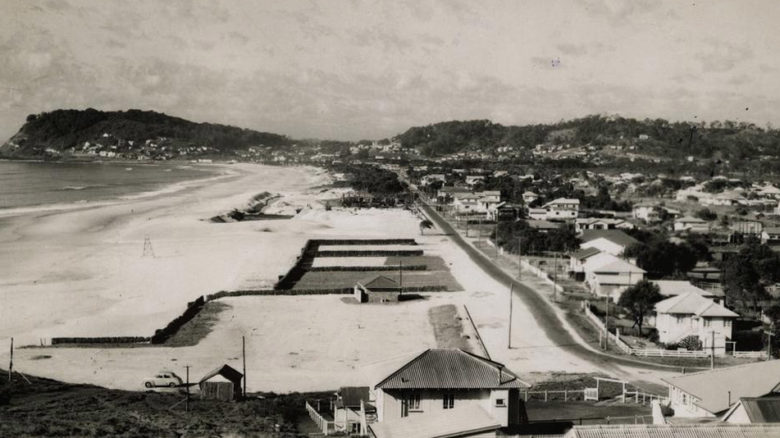

Aerial image of Burleigh Heads, circa 1952. Image: State Library QLD via Flickr

Aerial view of the Isle of Capri Surfers Paradise March 1973. Image: Qld State Archives

Cavill Avenue 1960. Low rise Surfers Paradise. Image: Qld State Archives

Murray Views at Burleigh Heads, circa 1954. Image: State Library QLD, Flickr

Most people are surprised to learn that the City of Gold Coast was a pioneer in town planning and development control, having introduced a planning scheme as far back as 1953. From the beginning there was an inherent intent to confine tall buildings around tourist hubs. Height controls were implemented through zoning. Buildings taller than four storeys were only allowed in areas zoned for Business and Shopping, and in a specific Residential B zone in some areas close to the ocean beach where the council sought to concentrate tourist accommodation.

Planning schemes, gazetted in 1963 and 1973, incrementally introduced development plot-ratios and density provisions to manage spatial graduation of intensity for high-rise accommodation.

Notably, the 1973 scheme mandated close attention to the design and treatment of the ground level. From that time the City of Gold Coast introduced requirements within planning schemes for communal open space and deep planting, as well as the concealment of refuse facilities. Basement car parking requirements were also introduced, with podiums not to exceed one metre above the natural ground level. All of these conditions facilitated the creation of subtropical gardens for enjoyment of the residents and guests, with the added benefit of greening and softening adjacent streetscapes.

From 1979-82 there was a remarkable surge in high-rise construction, which led to a strategic plan accompanying the planning scheme of 1982. Central area plans were introduced for the key centres, as the surge in high-rise construction continued throughout the 1980s. The result was the consolidation and concentration of tall buildings as a dominant feature of the Gold Coast’s image.

The next planning scheme gazetted in 1994 promoted a vision for a “City of Towers”. Height and density control maps were introduced along with a set of 16 prescriptive design provisions for high-rise development. These provisions fostered variety across a diversity of plot sizes and attributes, where the planning regulations generated many permutations. Seldom did two buildings emerge organically as the same. The overall result was an eclectic mix of slender towers with small footprints, sculpted forms and varied rooftop shapes.

Early planning schemes enabled generous set-backs and space for gardens. Image: Tory Jones

Belle Maison streetscape at Broadbeach. Image: Tory Jones

Subtropical gardens and generous open spaces are a feature of 1970s Gold Coast developments. Image: Tory Jones

Eclectic subtropical plantings amplify the Gold Coast's holiday resort vibe. Image: Tory Jones

Balconies and lush plantings emerged organically to create a distinctive Gold Coast aesthetic. Image: Tory Jones

Among this eclecticism however, there has been a consistent and faithful adherence to resort-style architecture. A hallmark of the Gold Coast’s tall buildings is a leisurely vibe that is distinct from the more serious, CBD office or apartment building. Thematic décor, sub-tropical landscaping, and features like port-cocheres, pools and tennis courts, create a palpable playful buoyancy.

The Gold Coast’s resort-style tall buildings characteristically have open balconies that articulate the facades. When viewed from outside, balconies give relief of shade and light and enhance three dimensional texture. For inhabitants, open balconies offer the potential to move casually between indoors and outdoors, and to linger and gaze out and around at the magnificence of the landscape, with views of the ocean, beach, city and mountains.

In 1997 Philip Goad, then deputy head of Architecture at the University of Melbourne, made a case for the architecture and urbanism of the Gold Coast within the Gold Coast Urban Heritage and Character Study, when he wrote “these are not New York’s cathedrals of commerce, but Queensland’s cathedrals of tourism.” He nicknamed Surfers Paradise “Miami Manhattan”, a resort-style of big city. In 2013 ARM Architecture and Topotek 1’s winning competition design for the Gold Coast Cultural Precinct picked up on this quintessential playful character of the city with a colourful, vertical art museum, topped with an observation deck and bungee jump.

Since the Integrated Planning Act 1997 prescription in town planning has become unpopular in Queensland. The Gold Coast’s last two planning scheme iterations in 2003 and 2016 have substantially banished prescriptive controls and introduced performance-based provisions. The current City Plan has profoundly deregulated high-rise building design and also catalyses renewal along the corridor of the light rail service, which commenced in 2014.

While Q1 (78-storeys) and Soul (77-storeys), set the scene for a race to the top, piercing the sky and dramatising the image of the city, these towering landmarks will soon be overshadowed by a new generation of super towers. City of Gold Coast has approved buildings for Southport and Surfers Paradise to be taller than 100 storeys. The skyline is punctuated by cranes. The 89-storey Spirit building is progressing on the site of the former 17-storey Iluka. Jewel is taking shape on the site of the former 15-storey Oriana. While not so relatively tall, the development’s trio of towers is broad and voluminous.

Jewel under construction. Image: John Gollings

Broadbeach development under construction, with zero set-backs. Image: Tory Jones

Jupiters Casino redevelopment at Broadbeach, with zero set-backs. Image: Tory Jones

Recent developments are removing street-level amenity. Image: Tory Jones

According to height control maps in the current City Plan we should expect to see taller buildings flanking both sides of the Gold Coast Highway from Labrador to Coolangatta. Some perceptible gradation will be maintained if development complies with the designated height limits, but it is realistic, and ironic, to anticipate that the clusters of high-rise development which have been misperceived as a spine, will in future merge to become a material reality.

The development industry’s prevailing lexicon today speaks not of “Miami Manhattan”, but of “Mini Manhattan”. New tall building typologies are more intense. They are also more homogenous in style and form. Most significant is the drastic change in the treatment of ground level.

In a Gold Coast Bulletin article Finn Jones, UDIA Gold Coast President described the 2020 Gold Coast as a fusion of New York and London, with the tramline stimulating a “vibrant cafe and small business culture”, which would help create “a unique experience of wonderfully expressive skyline and more intense street life”.

The 2016 City Plan reflected this new bigger city vision for thriving street life anywhere within cooee of the existing and future light rail corridor. Most significantly, the high-rise accommodation design code creates substantially greater potential building envelopes. The code omits plot ratio control and increases permissible site coverage. It also relaxes underground car parking quotients, and requirements for ground level greenery. Together, these changes enable building forms that will siphon amenity and activity from streetscapes. There will be little or no greenery or community gathering space at ground level. Any communal open spaces with gardens will be situated several storeys above street level, on top of deck car parking.

In some respects, the design code’s stated intentions for development do not seem to be supported by their corresponding “acceptable outcomes”. For example, the code calls for “tower form orientation and articulation that promotes sub-tropical design excellence and innovation”, yet amongst recent new buildings we witness a creeping sameness. Many have enclosed balconies (or belvederes as they are called in Q1) and fully-glazed facades like commercial office buildings. They seem bulkier and have a heavier impact on the aesthetic and micro-climate of streetscapes, creating wind tunnelling effects in particular.

A quintessential feature of the coastal sense of place is the pattern of east-west streets that intersect with the Gold Coast Highway and allow views to the ocean and to distant mountains. The 2016 City Plan expanded the locations where tall buildings are permissible, which means it is now likely that tall buildings will emerge along the western side of the Gold Coast Highway. Where these align with cross streets, they will truncate long views and twilight, eroding this urban quality. The new Darling Hotel building, in front of the Star Casino at the end of Elizabeth Avenue, Broadbeach, demonstrates the impact we can anticipate.

These and other manifestations resulting from current planning controls and decision-making seem unfavourable when presented with counter views. However, prevailing narrative in the city appears to accept that the light rail line justifies, even necessitates, taller and denser development, to achieve a desirably vibrant street life “like New York and London”. Others regard it as a Faustian pact and resent the nature and scale of change.

It is possible to see both sides of this argument, and new heights and density are not, in principle, necessarily bad. However, in lieu of references to New York and London, we should be talking about places like Waikiki, where development is dense and permeable, ground level greenery is abundant and the street life is vibrant with a palpable holiday vibe.

This is the realm of landscape architects. Sadly, their absence is conspicuous in conversations and reporting, and apparent in streetscape outcomes. The Gold Coast needs more landscape architects to lead the design of the ground level and the public/private interface of the city’s tall buildings. All built environment practitioners need to understand why it is important to conserve and enhance the resort-style qualities that make the Gold Coast distinctive.

Tory Jones has had a varied career in public sector urban planning, heritage conservation, design and project management. She is currently working on a research project at Bond University’s Abedian School of Architecture. Using her home City of Gold Coast as a case study, Tory is examining how urban narratives influence the development and identity of cities.