Beyond the palm tree: rethinking tropical urbanism

With many of the world’s fastest growing cities located within the tropics, and with Australia’s tropical north slowly migrating south, Foreground launches a new series of essays on tropical urbanism.

There are many, many different kinds of urbanisms, from green and resilient urbanism, to participatory and walkable urbanism. At first glance, the adjective ‘tropical’ may seem to provide simple qualification for yet another type of urban environ – one that just happens to be in the tropics. Yet coming to terms with design and development in this specific type of urbanism is slippery, in ways that are both fraught and super fun. Over the coming weeks Foreground will look at tropical urbanism with warm enthusiasm, to consider how our views and our landscapes simultaneously reflect and influence global concerns for the tropics and beyond.

The forthcoming series of essays, interviews and commentaries will explore the people, places and politics of environments and cultures in particular equatorial regions. And those regions are indeed particular – irreducible to either immaculate golden beaches, palms and fruity umbrella cocktails, or to steamy and mosquito-ridden backwaters. Australia’s tropical and subtropical landscapes are distinctive, although linked in many ways, to both our Pacific and northern neighbours and the lifestyles we observe and cultivate.

Along with unpacking clichés of place, a review of tropical urbanism should also unpeel clichés of influence and potential. What happens in the tropics, how tropical environments are and have been valued, how communities there manage their ongoing development and are empowered to do so, is of increasing and arguably vital importance for global trade and urban life.

James Cook University (JCU) has articulated ten reasons why the tropics matter – for everybody. These include acknowledging that almost half the world’s population live in the tropics, and over half the world’s children already live there. Tropical cities dominate lists of the fastest growing cities on earth, in population, trade, investment and wealth, including uptake of new technologies. The tropics also have the greatest cultural and species diversity, with economic, population and urban growth posing threats to this richness as well as to complex environments that regulate planetary weather. Tropical areas and the major cities within them such as Mumbai, Manilla, Jakarta, Bangkok, Bogota and Lagos, are increasingly prone to more destructive storms and heavy rains with climate change evident in the unpredictability and duration of extreme weather events and their expanding range.

Singapore is perhaps the apotheosis of the tropical city, with a population that is 100 percent urban. Image: Kelvin Zyteng

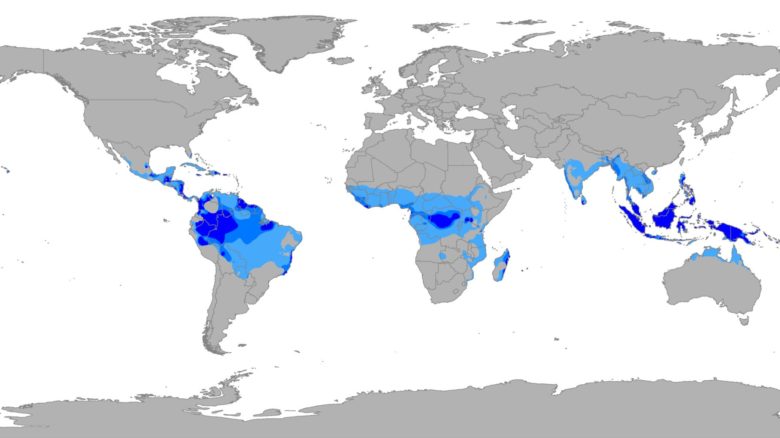

The tropical regions of the world, taken from the Koppen-Geiger climate classification map

Tropical cities often have an intimate relationship with water – both life-giving and life-threatening Image: Fancy Crave

Associate Professor Lisa Law leads a team at JCU concerned with the challenges faced by tropical cities. The Tropical Urbanism and Design Lab (TUDLab), whose name came from Cairns Regional Council’s award-winning city image study is “developing research and design capability in areas related to urbanism in the Tropics”. In the first of two articles from TUDLab, Law will examine Cairns, arguably Australia’s tropical urbanism capital and the subject of award-winning planning, policy and design endeavour. Its ongoing success, and that of other regional centres, may depend on a reconsideration of demographic shifts in tourism, from young people and families, to greying nomads. Visitor expectations are therefore also expected to shift towards authentic experiences based on local features, flora and fauna, in place of confected exotica.

Another article from TUDLab, written by Dr HanShe Lim, will consider the challenges of tropical rainfall patterns. Land development anywhere is predicated on reliable water supply and the regulation of storm-water, groundwater and wastewater. With growing concerns for urban resilience, there have recently been significant shifts in best practice approaches and attitudes to water, which finds its codified form in Water Sensitive Urban Design. However, adapting sustainable water practices developed in the temperate south, to very different conditions elsewhere, requires more than resized engineering.

Those design professionals that work within the field of tropical urbanism are aware of the dangers of mapping temperate solutions to tropical problems. They are trained and ready to grapple with extremes of heat, humidity, rainfall and other measurable climatic phenomena. The success or failure of their work is most typically judged by attending to improvements conceived in these terms, while admitting the growing complexities of climate shifts and nuances of site specificity. Within a wider cultural framing, however, the allure of tropics is often predicated on a sometimes perverse embrace of these very extremes. The tropics may be characterised by loud, hibiscus-flowery shirts and frangipani-and-lime fragrant fruits and seafood, but these also barely conceal rich, darker pleasures of explicit and implied excess.

Based in Cairns, the Tropical Urbanism and Design Lab explores urban solutions to tropical challenges Image: TUDLab

For many, the tropics is simply a place for fun. Image: Vicko Mozara

Many of the world’s fastest growing cities, such as Mumbai, are located within the tropics. Image: Don Chili

An exploration of the tropics as a cultural cypher reveals a place inhabited by the ghosts of colonial pasts: of dishevelled fecundity, vulgar decadence and savagery. Fever, disease and decay await both seekers and the unwary. There is primal fervour and magic in the tropics, a mix of Heart of Darkness racism and exploitation, tempered by Summer of the Seventeenth Doll and Travelling North seasonality and coming of age. In the tropics, the ‘City as Jungle’ actually is a jungle city. How much these murkier influences affect our urban perceptions is unclear, but it does seem fruitful to trace the psychoanalytic trails that have been an evergreen vine twining through art and literature on the tropics for well over a century.

Another cultural reading of the tropics takes us to the world of recreational rainforests and tropical luxuriance. More than manicured ficus and fronds is at play, however, when transplantating idealised ecosystems. We will explore the well-watered, if perhaps too-shiny, tropical artifice of hot-house corporate atria and hotel lobbies. Our guide will be Cassandra Chilton, a landscape architect and artist, who is adept at sifting productively through the layered ground litter of contemporary culture.

The shadier sides of tropical experience resonate beyond personal reflection and literary tradition. Land development in the tropics – globally, in the Pacific and in Australia’s north – is fraught with potentially patronising, if not openly exploitive, ‘global south’ concerns, stemming from collective, entrenched prejudices that we insufficiently interrogate. Trade and investment, and engagement with local communities and their cultures of public space use, concerns Andrew Mackenzie in his review of Port Villa’s foreshore development.

We will also consider Australia’s Gold Coast and its recent achievements, such as the ARM and Topotek competition-winning project that has provided the foundation to launch a new Home of the Arts (HOTA) at the Gold Coast. While large tropical public spaces are an opportunity to celebrate lush verdant landscapes, even modest tropical gardens are also wonderlands of exuberant flora and fauna. Landscape architect and town planner Shaun Walsh, is a self-confessed ‘compulsive gardener’. He talks with Foreground about gardening and the wealth of experiences enjoyed by gardeners, revealing and reveling in his ongoing project to dwell within a carefully planned and self-planted Queensland paradise.

Over the coming months Foreground will take you on a provocative tour of the tropics, with Jo Russell-Clarke as our guide. As guest editor for this Tropical Urbanism theme, she will lead us to the dappled shade of luxuriant gardens. We will brave the harsh glare of alien investment and the blistering pace of development. We will enrich jaded historical clichés with new critical and geographical nuance, while diving into the technical depths of managing complex and unstable tropical realities. We will detour to places of faux fecundity and have fun with evergreen favourites and failures.

Above all, Foreground will explore powerful new and necessary visions and rejuvenate our wonder at the tropical world.