The future of Melbourne’s parklets

With the lease of some parklets coming to an end, questions remain around the public value these spaces have added to Melbourne streets.

Outdoor dining on former parking spaces – generally known as parklets – has proliferated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reduced demand for parking coincided with increased demand for outdoor space – but when the pandemic subsides, cities must decide what comes next. Is this a temporary change before we return to the car-dependent city, or can it help us create a better city?

What has happened is that one kind of temporary private appropriation of public space (parking) has been traded for another (dining). This has been a very effective adaptation to the need for spatial distancing and to avoid indoor spaces. It has helped many hospitality businesses to survive.

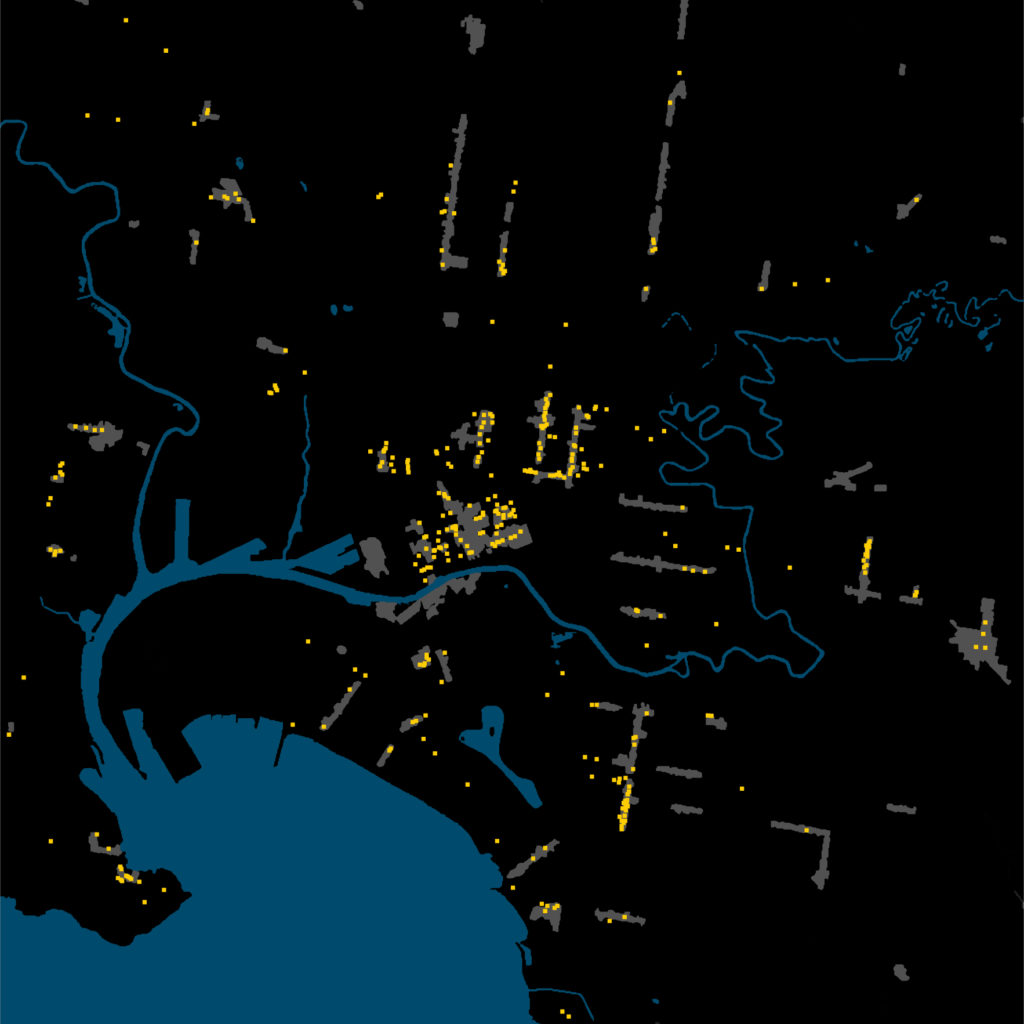

Parklets are concentrated in locations where restaurants and bars front onto walkable streets with limited footpath capacity and permanent strips of parking space. It is the future of these strips that is most immediately at stake. Where do public interests lie as we decide between a return to parking, retention of parklets, or some other uses?

To be sure, the use of public space for alfresco dining and drinking has a public benefit that parking does not. Parklets contribute to the atmosphere, vitality and sense of place of the street. Increased social activity also makes the area safer.

Yet street parking is a public amenity too. Our cities’ long-standing dependency on private cars will not vanish overnight. As the pandemic abates, the demand for parking will return, along with the lure of parking revenue for local councils.

However, the costs and benefits of urban driving and parking are rapidly changing due to lower speed limits, congestion charging, ridesharing and ultimately autonomous vehicles.

It’s not an either-or choice

A first point here is that we do not need to choose between parking and parklets because they are highly interchangeable. With a standard area of about 2 metres by 5 metres, parklets can be created and removed flexibly and in stages. Parking and parklets can be complementary: the two functions could interchange according to user preferences over daily, weekly and seasonal cycles.

Parklets first emerged in San Francisco, as an urban guerrilla movement briefly turned parking spaces into public parks while feeding the meter. These parklets were defiantly public – turning private parking into publicly accessible space.

If we decide to retain parklets, then should they only be available for commercial appropriation, or also for pocket parks and mini-plazas with free and open access? And what other uses and designs are possible?

We might re-imagine the parking strip as a territory that is variously available for uses ranging from picnics, parties, market stalls, street vendors and urban greening to parking, restaurants and bars. Uses that involve private appropriation could continue to be a source of local government revenue.

However, the key is identifying the planning and design frameworks that maximise public benefit from scarce and valuable public spaces. While local businesses and residents have often become dependent on nearby street parking, there is no natural right to such private appropriation. On what basis should a business proprietor or resident have first access to a parking space if there is a better public use?

Don’t forget bike lanes

The other key competitor for this space is cycle lanes. Cycling is the best prospect for easing pressure on roads and public transport. With driving in our cities above pre-pandemic levels, the case for dedicated cycle lanes is now overwhelming.

For trips of up to 20 minutes, cycling enables access to an area about nine times greater than walking and often gives better access than driving or public transport. As bike lanes make cycling safer and faster, many more of us ride bikes instead of driving. Safe cycling requires lanes about 2m wide, the same as a parking strip – but in many streets they are in competition for the same space.

The question of what comes next for parklets requires us to take a detailed look at the structure of each particular street. Some streets already have wide footpaths and the parklets are a bonus. Others have more traffic lanes than needed, and that width might be reallocated for parklets.

Main streets often have buses and trams that provide additional benefits and constraints. Adjacent, quieter and safer streets might be better for cycle lanes.

Flexible solutions are likely to work best

Innovative options will likely involve dynamic outcomes involving both parking and parklets. The parking strip might morph incrementally into a mix of parking, parklets, mini-parks and mini-plazas, with local demand determining the outcome. Another prospect is a mix of expanded footpath, cycle lane and calmed traffic.

The different mixes may change with daily or seasonal rhythms, much as parking already yields to rush-hour clearways. Parklets might compete with car parking on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Rather than determining fixed outcomes, we should encourage a diversity of experiments from which we learn and adapt. Indeed, the proliferation of parklets can be seen as an experiment that works in many ways and not in others. Perhaps understandably, far too many are makeshift with minimal design and hampered by bureaucratic conventions. Many are little used for much of the time, just like parking spaces.

The pandemic has presented the best opportunity we will see for transformative change in our streets. There is huge scope for imaginative design and planning as we explore the possibilities.

After a century or so of surrendering public space to the car, large amounts have been reclaimed for active social use. Public space was allocated for car parking in an earlier era when cars represented the freedom of the city. But when times change we should change the city.

If we hope for something better than a return to car dependency or further privatisation of public space, then the thinking about what happens next needs to start now.

Professor Kim Dovey is Chair of Architecture and Urban Design at Melbourne University

Merrick Morley is a PhD Candidate at the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Melbourne

Proffessor Quentin Stevens is Associate Professor, School of Architecture and Urban Design, RMIT University

This article was first published in The Conversation.

![]()