Tree change: What happens when living heritage becomes dead wood?

Robin Boyd’s Walsh Street house had a ‘significant tree’ that became a 25-metre-tall significant problem. But there’s life in those bones yet.

“It’s a bit ironic, isn’t it, given what Robin Boyd wrote about Arboraphobes,” Tony Isaacson, chair of the Robin Boyd Foundation, says from his chair in the once-radical open plan living area of 290 Walsh Street, South Yarra, the house Boyd designed and built for his family in 1957.

Isaacson has raised his voice, just a fraction, to account for the distinctive whine of a chainsaw blade, biting into wood. Outside, a team of workers are busy felling the Walsh Street property’s most significant tree: the Monterey Pine that for more than six decades has greeted visitors on arrival.

The Monterey Pine was already a mature tree when Boyd bought the property, which sits on a hill a half-hour walk upriver from Melbourne’s CBD. Growing just off-centre of the site’s street side boundary, Boyd must have recognised it would make for an impressive gatekeeper – in lieu of an actual gate, that is, given his original plans didn’t actually have one, or a front fence for that matter. The tree’s soaring trunk and broad canopy marked the entrance to the property, and Boyd would complement it with vertiginous open steps shooting up from its roots, across a steep drop, to the house’s first floor entry.

The Walsh Street house is one of Australia’s most important works of modernist residential architecture and accordingly is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register. The listing recognises that Boyd sited the house so as to preserve the Monterey Pine. As Isaacson points out, this means that there are two things the register protects – the house and the tree, and any significant changes to either require a permit from Heritage Victoria.

Protecting a building from change, or even just extending the life of the bits we might think are valuable, is a difficult undertaking. Some building owners fight long, bitter battles to prevent or remove heritage listing. Heritage protection can be costly, with expensive repairs and increased insurance premiums both likely. It also makes it difficult to change the building to meet shifting occupant needs and expectations, or cope with the many outrages, large and small, it might suffer over time.

Good architecture is responsive to both its cultural and environmental contexts, and is dependant on them for much of its value and its function. Most heritage bodies recognise this contingency, and at the very least pay lip service to the ambition of a living architecture that can accommodate some change to usage and context as the building ages. Things become much more complicated, though, when the subject of a heritage listing is actually living – or, as in the case of the Walsh Street Monterey Pine, was living, and then died.

The Robin Boyd Foundation had known since at least 2010 that the pine was senescent. A landscape maintenance study prepared by John Patrick Landscape Architects in 2017 suggested, though, that while the tree was in poor health at that stage, with the right care and treatment it might also live for another five to 10 years. Street services excavation work combined with two years of drought put paid to that hope. By October 2019 it was obvious that the foundation needed to remove the tree, which at roughly 25-metres tall loomed not only over the Boyd house and adjacent busy street, but also the nearby Melbourne Girls Grammar school.

In his bestselling book The Australian Ugliness, first published in 1960, Boyd devoted an entire chapter to a jeremiad against what he saw as Australia’s interrelated compulsions of “aboraphobia” (a.k.a. dendrophobia) and tabula rasa development. Boyd was appalled by the post-war flattening of Australia’s historic buildings and natural assets for ever-newer, ever-bigger cities. As he put it, “For every new member joining a tree preservation society or a National Trust branch there is at least one more suburban pioneer sharpening his axe.”

Despite his recent canonisation as Australia’s preeminent priest of mid-century modernism, Boyd was actually one of the country’s earliest proponents of heritage preservation. His biographer Geofrey Serle identified Boyd’s book Australia’s Home, published in 1952 and still in print today, as a ground-breaking work of Australian architectural history with lasting influence on the heritage movement. Boyd was also as tireless a champion of indigenous flora in residential gardens as he was a relentless critic of the tightly clipped “European” gardens that Australians tended to prefer (“even if one has to hold a hose all evening to keep the English grass green and the daphne alive,” as he put it).

Small wonder, then, that when it came to the construction of his own house on the newly subdivided ‘Prineyeh’ historic estate in South Yarra, Boyd opted to preserve some of the existing vegetation and heritage elements he found on site. This includes the pine, which the foundation’s heritage consultants believe might be a remnant of an avenue of trees that once graced the estate, and a stonework fountain and retention walls just below it.

Preserving Boyd’s preservation efforts is proving to be an expensive and complicated task for the foundation, rich with ironies the satirist in him might well have appreciated. Pinus radiata, the tree’s species, is introduced. Unlike the equally foreign European garden flora Boyd railed against as wildly unsuitable to Australia’s climate, though, the species is originally from hot, dry California, and therefore does phenomenally well in the country – so much so in fact that it is classified as an environmental weed. This puts the foundation and Heritage Victoria in the unenviable position of having to choose between heritage preservation best practice, that would see like replaced with like, and environmental best practice, that wouldn’t see government bodies forcing non-profit organisations to plant and nurture pest species in suburban gardens.

Furthermore, because the tree is heritage-listed, under Heritage Victoria requirements it needs to be documented before it is removed – even if what is being documented is essentially a corpse.

Isaacson estimated that removing and replacing this particular dead tree could cost the Robin Boyd Foundation more than $50,000 – a daunting sum for a non-profit organisation dependant on donations for survival. To help with the removal and its consequences, the foundation enlisted the help of a tiny army of specialist volunteers: there was John Patrick Landscape Architects (who prepared the nine-page tree removal plan); there were the tree removalists (a team of at least five by my count on the day, who came with a crane, two trucks and a mulcher); and there was the photographer, John Gollings, who put his hand up to help document the tree and its removal. Additionally, there was landscape architecture practice Openwork, who volunteered to help the foundation explore ways the tree could be commemorated and perhaps find some productive outcomes from this otherwise costly and unfortunate exercise.

John Patrick Landscape’s removal report recommended the foundation replace the dead tree with a similar, less weedy species – Pinus canariensis, or Canary Island Pine. Heritage Victoria agreed to this as a good compromise and the foundation will be grubbing out the roots of the previous tree and planting a specimen once the conditions are right. But, as John Patrick Landscape’s report noted, it will take at least 20 years to achieve anything close to a ‘mature’, suitably striking state. How then to make sense of the absence, given Boyd designed the house to work in conjunction with this imposing arboreal guardian? How to ensure some indication of Boyd’s intent remains, and that we will remember to remember it, now that the tree is gone?

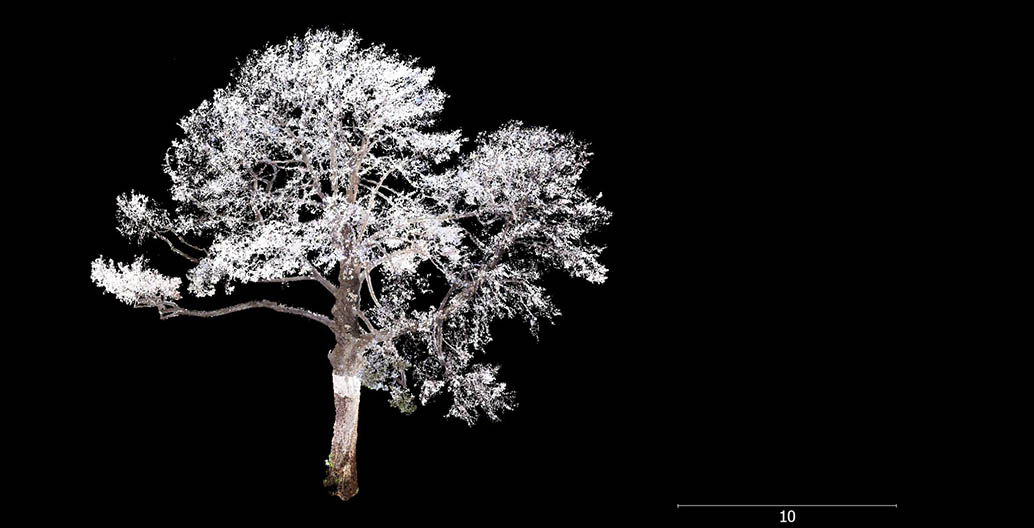

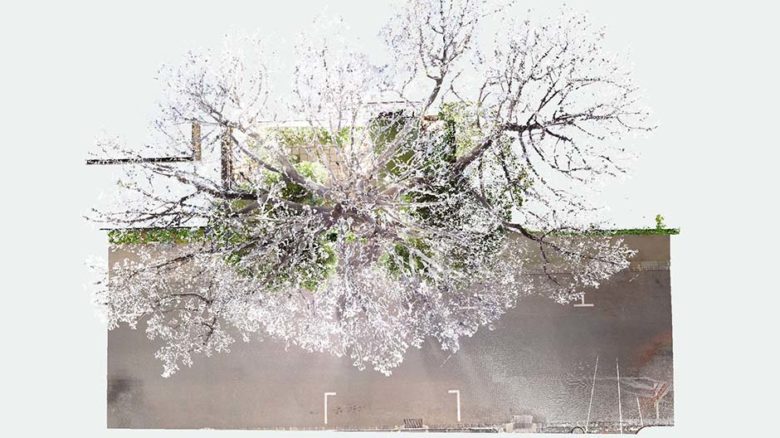

Point cloud scan of the Monterrey Pine at Boyd's house at 290 Walsh Street. Image: Yazid Ninsalam

Point cloud scan of the Monterrey Pine at Boyd's house at 290 Walsh Street. Image: Yazid Ninsalam

Point cloud scan of the Monterrey Pine at Boyd's house at 290 Walsh Street. Image: Yazid Ninsalam

One part of the solution the foundation is exploring might see the tree’s carcass gain a second life as finely crafted furniture – a memorial of sorts, but one that the foundation could auction off to help raise funds to cover the costs of upkeep for the Walsh Street building and gardens. Openwork also arranged for Dr Yazid Ninsalam of RMIT University to produce a point cloud scan of the tree, which captures its three-dimensional form as a granular, highly detailed digital shade. In the right virtual environment, this phantom pine could conceivably live on for an eternity.

Documenting, removing and replacing the tree in this way is a lot of trouble and potential expense to go to, and I ask Isaacson if there weren’t simpler alternatives. He tells me that at one stage the idea of crudely making the remnants of the tree safe by lopping off the dangerous stuff and leaving a stump was floating around, but the foundation never seriously considered it. They were always going to replant.

“We won’t be here to see it in its full grandeur, but it’s not about us,” says Isaacson. “Trees are about the generations to come.”

Heritage, then, that is as much about a hopeful vision for the future as it is about the past – a philosophical sentiment amply supported by the writings of Australia’s most influential midcentury modernist.

–

Maitiu Ward is a publisher and editor of Foreground.

The Robin Boyd Foundation is currently raising funds to cover the costs of restoring the gardens of Robin Boyd’s iconic Walsh Street residence. Click here to donate or find out more about the campaign.