Reimagining Australia’s “temperate Kakadu”

Unlike Sydney, for most of its history Melbourne’s been a city that’s turned its back on the water. Prior to colonisation, the land around the CBD was home to Billabongs, creeks and swamps. It’s this history that’s coming straight back into focus as inner-city redevelopments return to the wetlands.

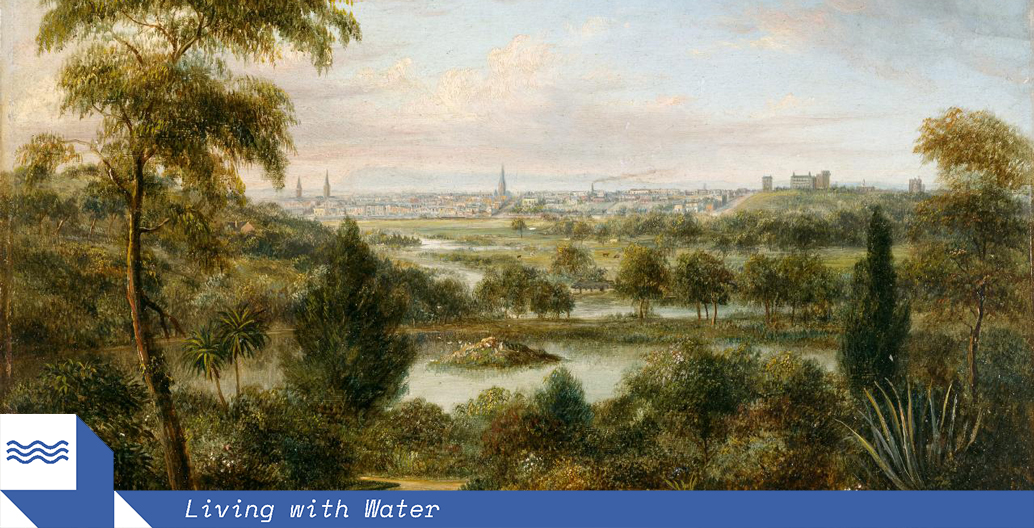

“A limpid river flowed over a rocky waterfall known as the ‘Yarra Yarra’, at what is now the foot of Market Street, before debouching into a large, deep pool at the head of a paperbark-lined estuary. Billabongs and swamps were sprinkled right around the bay, and they teemed with brolgas, magpie-geese, Cape Barren geese, swans, ducks, eels and frogs. So abundant was the wildlife that we can imagine the Melbourne area in 1830 as a sort of temperate Kakadu, and, as in Arnhem Land, it was the wetlands that were the focus of life.”

— Tim Flannery, The Birth of Melbourne (2002)

Little is left of the “temperate Kakadu” that greeted Melbourne’s British settlers. John Batman, the patriarch of the city, fresh from the spoils of the Black War in what was then known as Van Diemen’s Land, had come to the banks of the Yarra to set up an outpost of the colony of New South Wales. From early European accounts, the landscape presented was described as one of abundance. This was no accident, with the area’s Indigenous inhabitants tending to many productive wetlands, creeks and waterways and their surrounding vegetation.

Most of this landscape has long since been paved over, but this otherwise forgotten history occasionally resurfaces when urban redevelopment plans around the Hoddle Grid have been mooted, such as 2015’s thought-bubble to return inner city Elizabeth Street to the seasonal creek it once was. That, of course, partly explains why Elizabeth Street is the CBD’s thoroughfare that remains most vulnerable to flooding (currently, what’s left of the creek is an underground pipe spilling out into the Yarra).

But there are pre-colonial waterways that aren’t as well-known, only remaining in the history books, such as the Blue Lake originally surrounding Flagstaff Gardens, as illustrated by the early settler, George Gordon McCrae:

“[It was] intensely blue, nearly oval and full of the clearest salt water; but this by no means deep. Fringed gaily all around mesembryanthemum (‘pig-face’) in full bloom, it seemed in the broad sunshine as though girdled about with a belt of magenta fire. The ground gradually sloping down toward the lake was empurpled, but patchily, in the same manner, though perhaps not quite so brilliantly, while the whole air was heavy with the mingled odours of the golden myrrnong flowers and purple fringed lilies, or ratafias. Curlews, ibises and ‘blue cranes’ were there in numbers … black swans occasionally visited it, as also flocks of wild ducks.”

The reason for this loss of ecological diversity? Capital. Rapidly growing Melbourne would soon become the world’s richest city in a matter of decades thanks to the gold rush – a city that grew from 95,000 in 1851 to 500,000 by 1858. Marching to the beat of progress and new-found wealth, this kick-started a land and property boom that created the inner-suburbs remaining today. What resulted was the destruction of verdant ponds, swamps, and creeks that ran between Williamstown and St Kilda – even the Yarra wasn’t spared, with its rock bar blasted in 1879 to straighten and widen it. Over subsequent centuries, Melbourne’s urban development turned away from water, as its swampy western fringe proved too difficult to develop for budding city-makers.

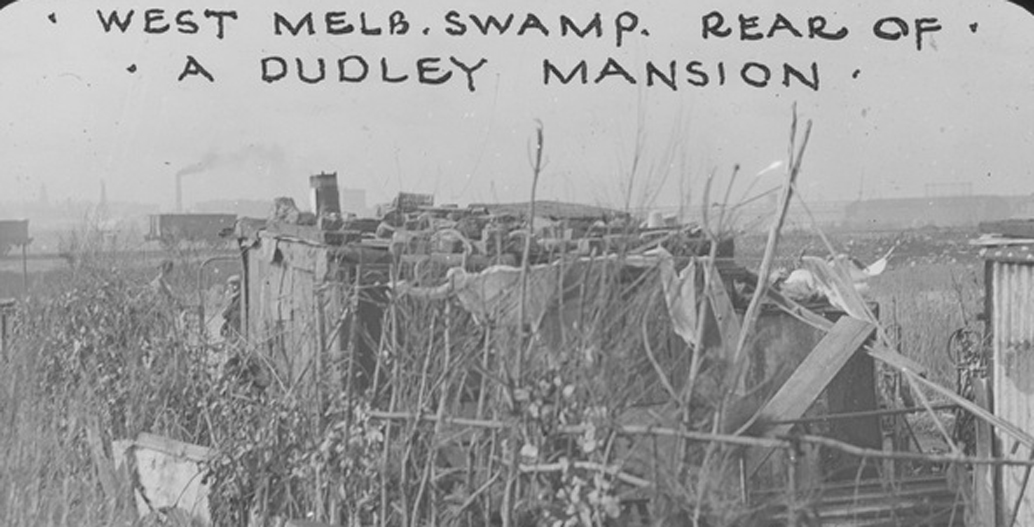

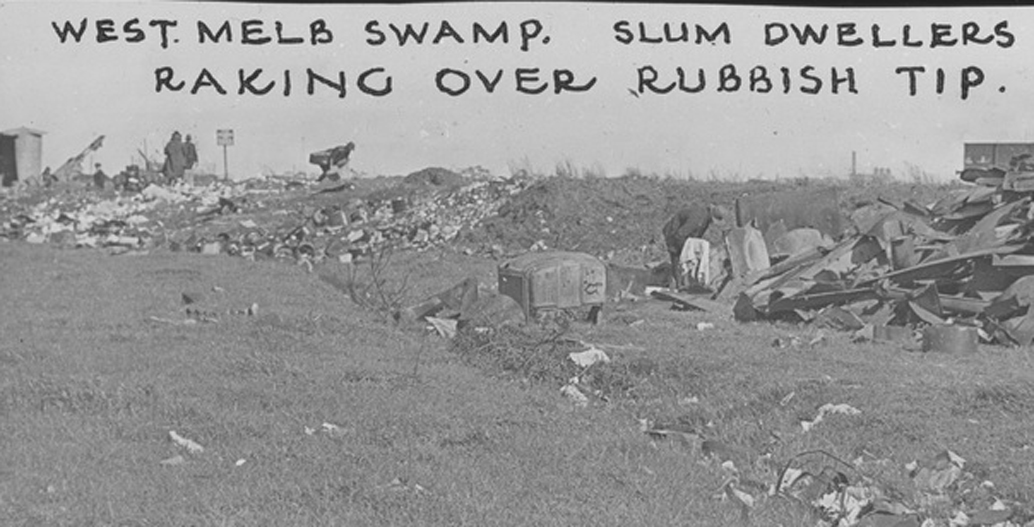

That context still divides the city today. Compared to the verdant, sprawling suburbs in the city’s southeast, Melbourne’s west – when seen from above – pales in comparison. In place of suburban heritage, there are siloes, sheds, and factories making up the industrial patchwork quilt that still cloaks the area. For land west of the city, swampland would become rubbish tips, to then be built over, to become the dumping ground of industry.

The swamp was home to makeshift properties made from found materials found in the tip.

‘Batmans Hill Melbourne, looking west’, Robert Russell / State Library of Victoria (1837).

West Melbourne swamp slums circa 1930s.

West Melbourne rubbish tip. Image: Oswald Barnett Collection, SLV.

But times are changing. Looking at the spread of inner Melbourne’s 21st-century inner development, the city is destined to return to water. Docklands, Fisherman’s Bend, and Arden-Macaulay are all emerging inner-urban developments that sit around the former Yarra delta, with adjacent developments in E-Gate and Dynon to follow-suit. The question of how this will be done well is taxing the creative and administrative capacities of a veritable troupe of bodies, including the Melbourne Metro Rail Authority, Melbourne Water, the City of Melbourne, the Victorian Planning Authority, and of course, the Andrews’ state Labor government, which is staking significant economic and political capital on doing things right.

Over the next few years, attention will focus on Arden-Macaulay, a prized pocket of inner-urban creekside land, spanning a total of 144 hectares. Formerly home to the West Melbourne swamp (later, a dump), the site straddles the Moonee Ponds Creek where it meets the Yarra, with development set to form the missing link between North Melbourne and Kensington. By the early 2020s, it will also form part of Melbourne Metro, the new underground rail system currently under development. By 2051, this precinct is billed to create up to 34,000 jobs and play home to 15,000 residents, a time when, it should also be stressed, Melbourne is projected to have overtaken Sydney as Australia’s largest city.

The alien alcoves created by Melbourne's Citylink freeway have been touted by bodies such as Film Victoria.

Moonee Ponds Creek looking toward Flemington from Macaulay Station.

Melbourne's Capital City cycling trail runs alongside Moonee Ponds Creek, often out of action due to flooding.

The site billed for the new North Melbourne station as part of the Melbourne Metro.

The land adjacent to Moonee Ponds Creek have traditionally been VicTrack rail yards.

Currently, water views in Arden have been reserved for the rail depot.

Writing in the precinct’s draft vision statement, Melbourne’s Lord Mayor Robert Doyle voiced the lofty intentions for the area:

“Few major world cities are afforded the opportunity to renew an underused 144 hectare growth area within their boundaries. The transition from manufacturing to a knowledge- based economy has left inner Melbourne with expanses of underutilised industrial land. The Arden-Macaulay precinct represents an opportunity to accommodate an expanding central city and transform this area into a sustainable living and working environment.”

Evidently, a lot is riding on the ‘success’ of this renewal precinct, but it also has a lot going for it. It’s a short tram ride from the CBD, it will soon have a Melbourne Metro station , and it sits in close proximity to the city’s “knowledge cluster” of hospitals and universities.

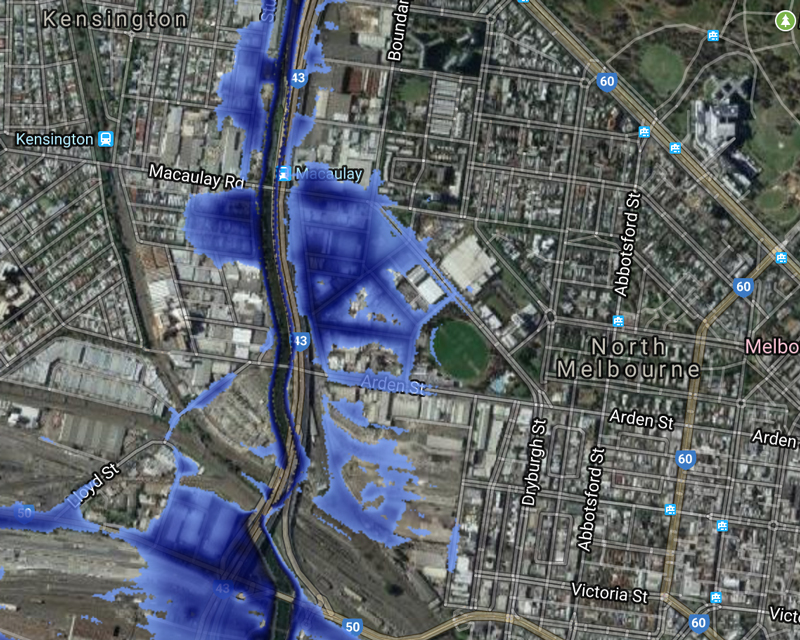

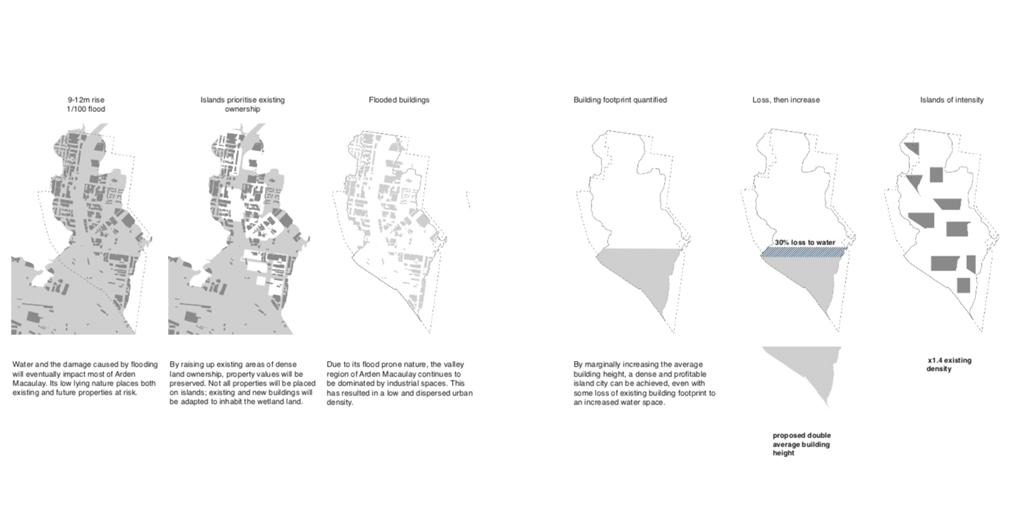

But there’s a catch. As the redevelopment of Southbank and Fisherman’s Bend has demonstrated, Melbourne’s return to water also signals a return to risk, as much like these two urban areas, Arden-Macaulay also sits on a floodplain. Judging from the maps contained within the area’s draft vision frameworks, a sizable portion of land will be subject to inundation, which will no doubt be amplified if sea levels rise to the worst-case scenario of 2.7 metres.

Arden-Macaulay at 2.7m

How this is managed is a question that’s been mulled over by pundits and pollies alike, and at present, there isn’t a clear answer. What some do know is that they don’t want a repeat of the multi-level car-park lined streets of Southbank and Fisherman’s Bend – a crude approach to mitigating flood risk. But others have taken this as an opportunity to ask bigger questions about what constitutes a city and what Melbourne could be, in 50 to 100 years’ time.

“Given that we know what risks are associated with climate change, and we know that Melbourne’s a social and technological hub, the question is: How would we do it differently?” says Nigel Bertram, Director of NMBW Architects and Practice Professor of Architecture at Monash University’s Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture (MADA). “When you look at the clash between the underlying environmental conditions of Arden-Macaulay and its predicted urban intensification there’s obvious tension. Looked at simply, there is the proximity-based logic of locating the knowledge economy, with transport efficiency and opportunities for day-to-day human contact that inner Melbourne has been very good at. But there are bigger questions here about the underlying scale and nature of these low-lying redevelopment areas – they’re part of the much larger previous swampland, which operates on a different scale and is difficult to reconcile with urban experience. It is connected and impacted by systems beyond the site and these impacts will increase with climate change.”

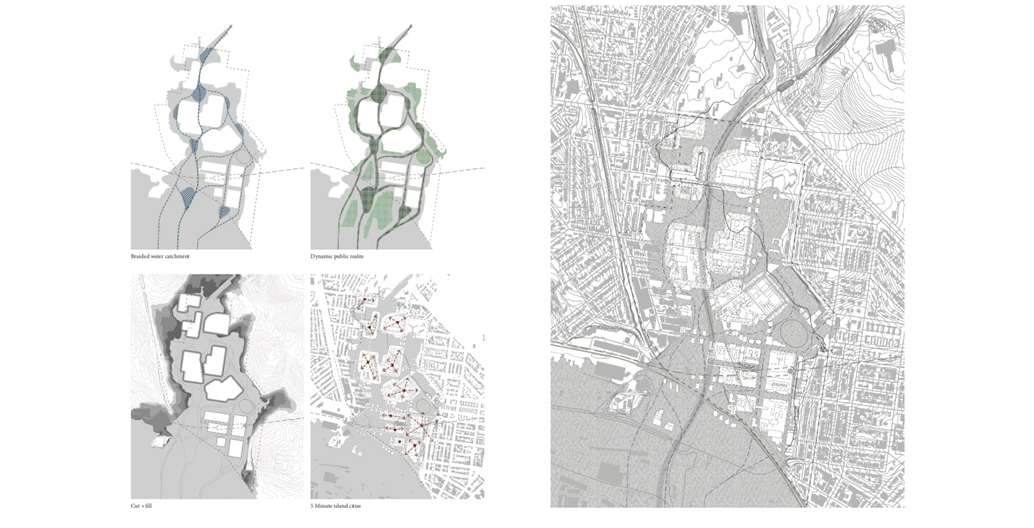

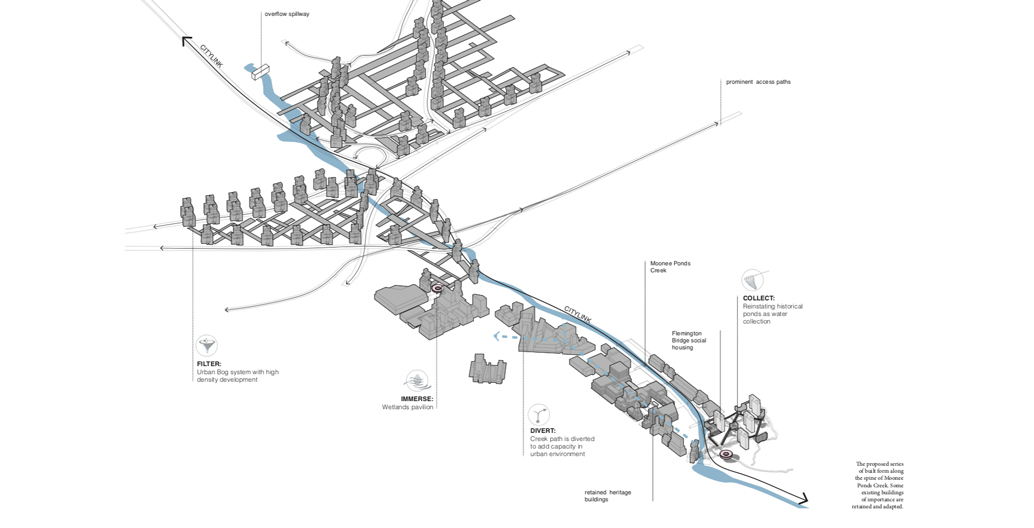

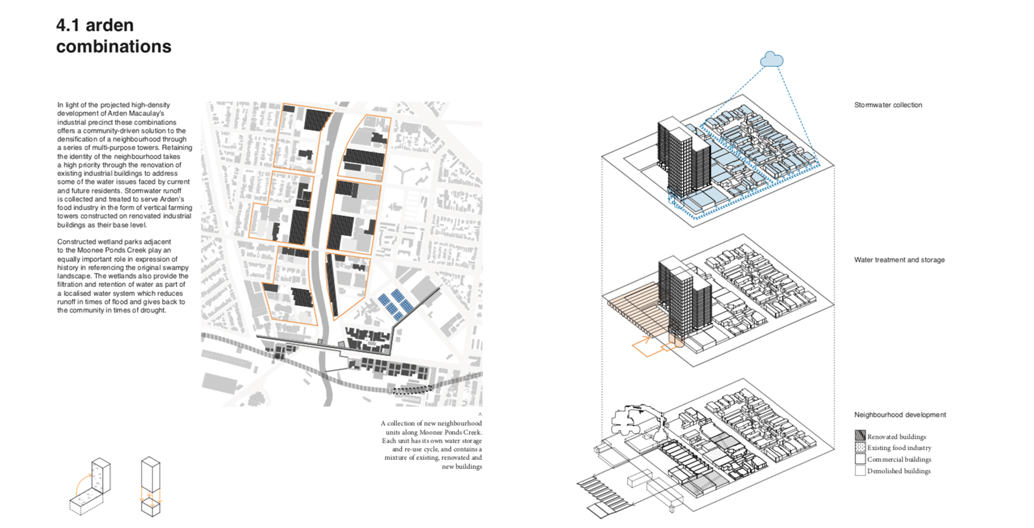

In 2017, Bertram, along with Catherine Murphy, Rutger Pasman and Oscar Sainsbury, ran the aptly-titled MADA Masters studio Swamp City, as part of the Cooperative Research Centre for Water Sensitive Cities (CRCWSC). This looked at “future scenarios for Arden-Macaulay”, fusing Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) principles with potential urban scenarios that would instigate high urban amenity. What resulted was ‘Arden Macaulay in Transition’, a research paper describing four differing, but complementary adaptive design proposals for the area. While each proposal is centred around the Moonee Ponds Creek, each differ just slightly, emphasising different strategies and water routes to conceptualise a holistic future development.

Moonee Ponds Creek looking north from Macaulay Station.

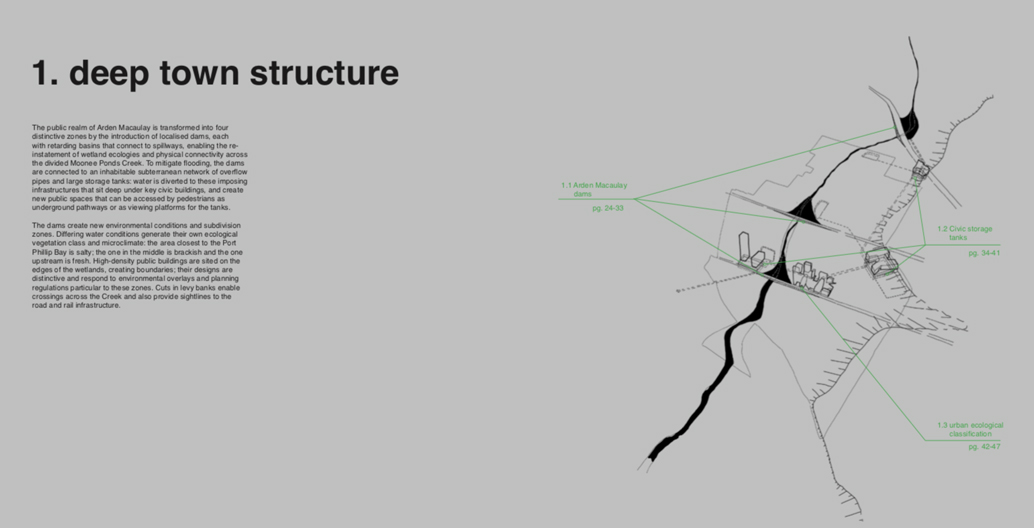

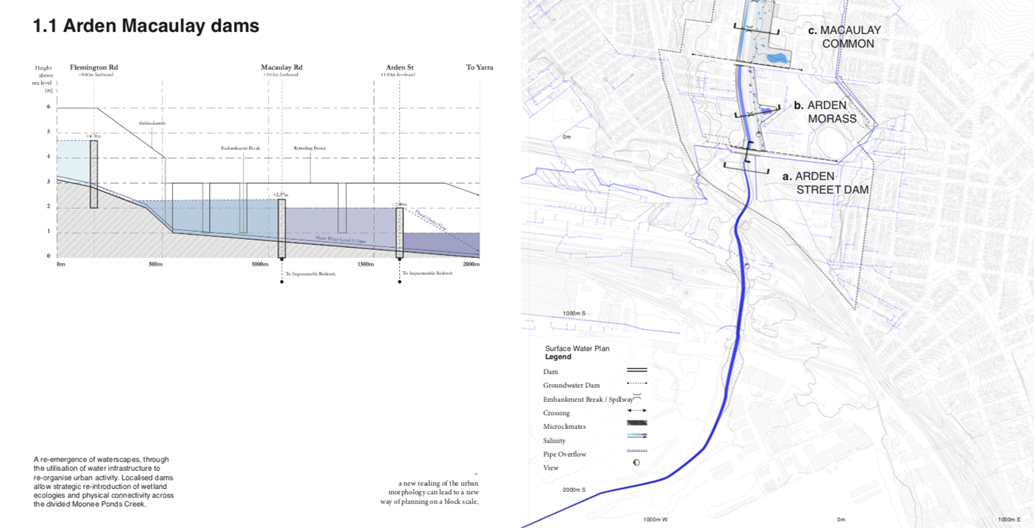

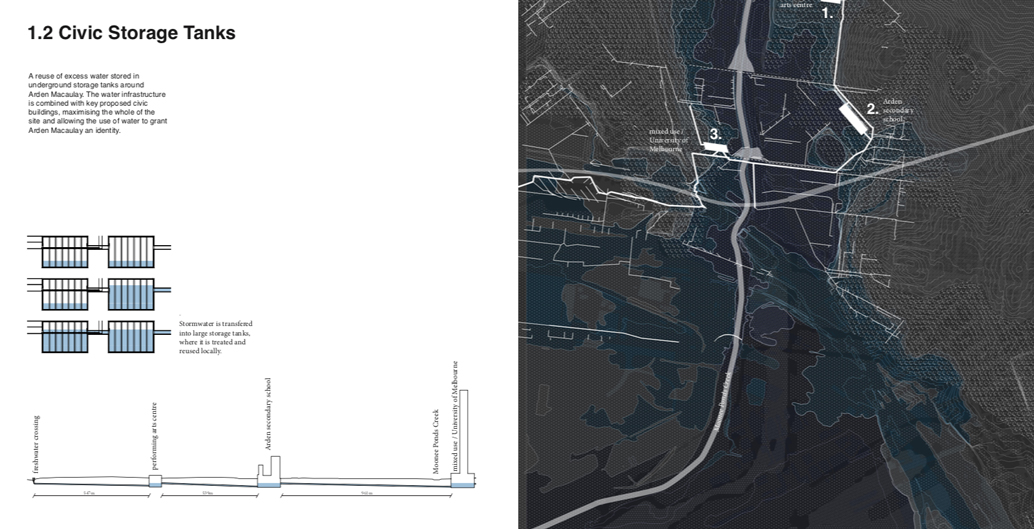

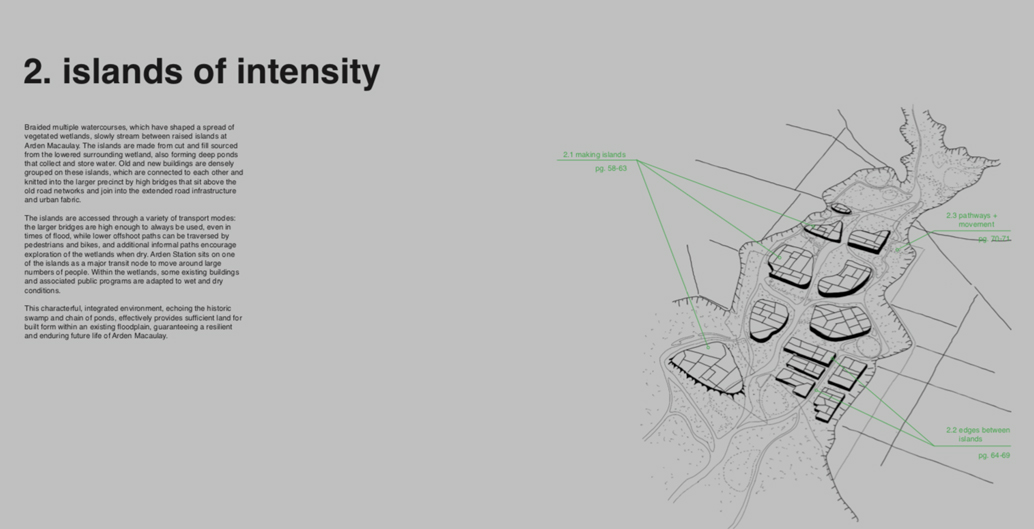

The first two, ‘Deep town structure’ and ‘Islands of intensity’, centre water as a direct and visible part of daily life, differing depending on the volume of water present. The former splits the Arden-Macaulay section of the Moonee Ponds Creek into four distinct zones through the use of dams paired with corresponding retarding basins, connected to a series subterranean network of pipes and tanks designed to collect overflows in times of flood. The latter is a tad more ambitious. Instead of the city perching on banks, the area is situated within braided watercourses, essentially a city within a wetland sitting on raised islands. Here, a porous, sponge city environment brings the area closest to what it was before – a meeting place with water at its core.

“The first two operate on an infrastructural level. The first one, through a series of dams, create brackish and semi-brackish estuarine conditions. If planners were to develop that more strategically and be able to manage it in flood and drought conditions, you would end up with ecosystems and microclimates that would be specific to that level of salinity in the water – as it happens in a natural system,” says Bertram.

“For the second, we reconstituted Arden-Macaulay not as land but water in which there were islands of high-density of development, inverting traditional flood-planning. Rather this as ‘defence’ with high levy banks, we thought about widening waterways to its natural floodplain condition and within that, weave islands of high density islands – in the studio we described them as castles.”

The ‘deep town’ proposal uses civic buildings to mitigate flood risk. Image: MADA

A new groundwater-fed swamp covered with couch grassland and absorbent peat moss. Image: MADA.

Dams propose a re-emergence of waterscapes, using infrastructure to re-organise urban activity. Image: MADA

An overview of the civic water storage tanks. Image: MADA

The ‘islands of intensity’ proposals mark a radical shift in Melbourne flood management. Image: MADA

By allowing the creek to meander across the valley, water is brought into the fabric of Arden Macaulay. Image: MADA

The islands are proposed to be a five-minute walking distance from each other. Image: MADA

Image: MADA

View from a restored Moonee ponds creek floodplain towards high-density islands of development. Image: MADA

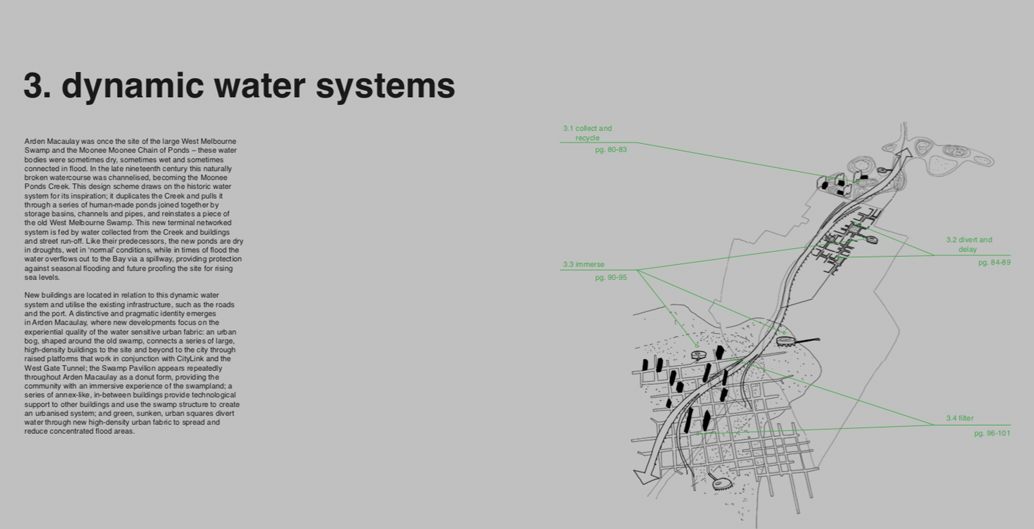

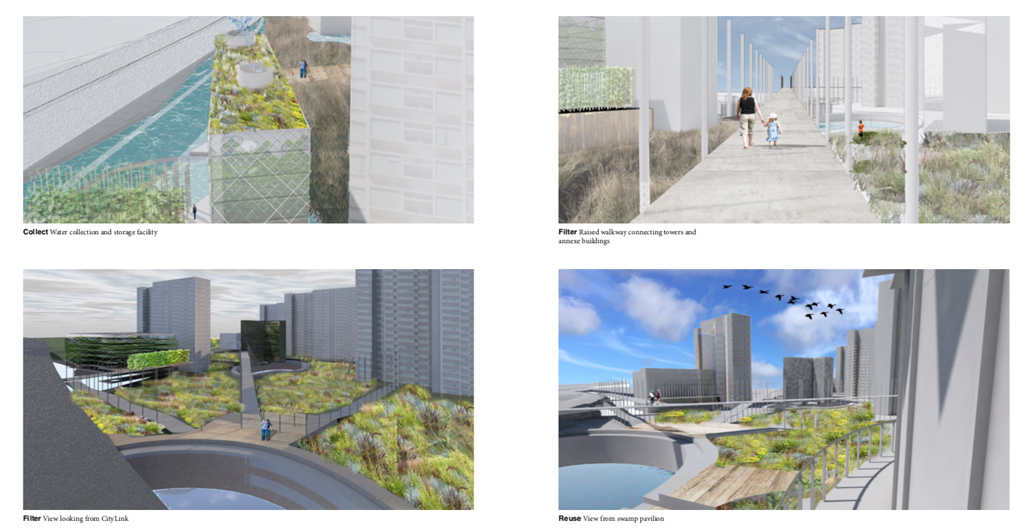

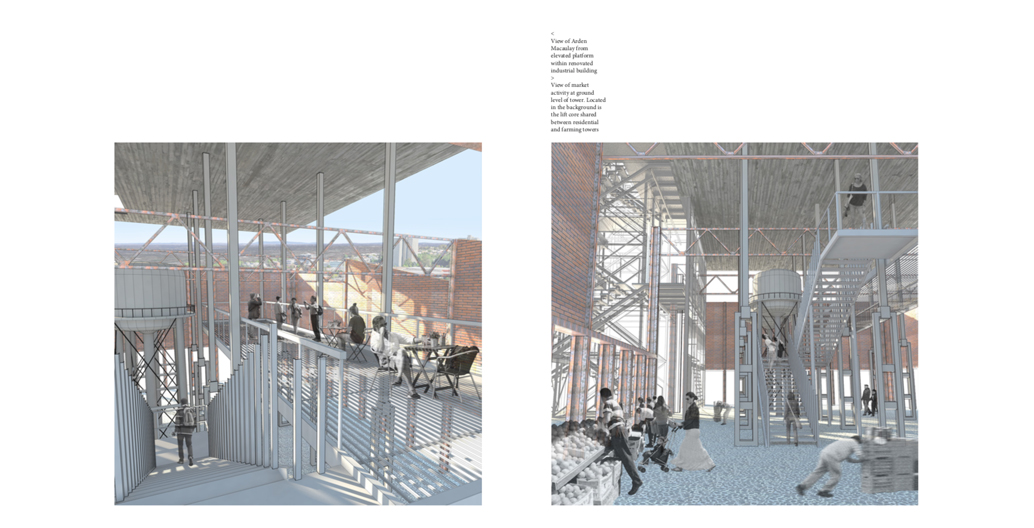

Proposals three (Dynamic water systems) and four (New industry neighbourhoods) draw upon the site’s existing built and environmental heritage. With Arden-Macaulay sitting on the site of the West Melbourne swamp, the former proposal duplicates the Moonee Ponds Creek, pulling parts of it through a series of constructed ponds connected via storage basins, channels and pipes. For residents, flood mitigation isn’t something to be made invisible, marking an opportunity where “new developments focus on the experiential quality of the water sensitive urban fabric”. Following on from this, proposal four utilises the area’s existing industrial heritage blending water sensitive principles to create a new idea of post-industrial character. The remaining buildings would be retrofitted in order to create a patchwork of self-contained villages, moving water through via open spaces that absorb, divert, alter and reuse it during normal and flood conditions – even the conversion of a silo into a vertical farm tower (housing water storage tanks) has been mooted.

The dynamic water systems seek to create new public space as a form of flood management. Image: MADA

This proposal seeks to bring back the lakes that were scattered around the Yarra delta. Image: MADA

The different typologies of the dynamic water systems. Image: MADA

The new industry neighbourhoods are designed to get residents thinking about flood resilience. Image: MADA

Types of public and private channels water may run through. Image: MADA

A vision of a vertical farm tower. Image: MADA

“We weren’t looking to reinstate nature, but we were looking to see how we could create a wetland quality at the heart of Arden-Macaulay’s density,” says Bertram. “To make this evocative, desirable and responsible, being water sensitive was one of many methods to use in order to create a locality with open space, access to waterways, and an ability to provide a quality public realm in times of drought and flood.”

“The government wants Arden-Macaulay to attract people who participate in the ‘knowledge economy’. If we’re to reconstitute this part of the city with water at the front of mind, this could not only solve the functional problems of the area, but provide the high amenity that would make it uniquely attractive on a global scale… but if it’s going to be a crappy place, it’s not going to be the place that you choose to relocate to from Boston.”

Artist’s impression of central Arden. Image: Victorian Planning Authority.

Many would argue Melbourne has a track record of producing crappy places of late. It’s most recent attempt to re-orient itself to the water is Docklands, which has been described as a “soulless, dispiriting, windswept failure”. Kick-started in the late-90s, the project saw a cluster of large developers including MAB, Mirvac and Walker Corporation in collaboration with VicUrban (now Places Victoria) and the Victorian Government launch a flurry of construction activity, lifting the formerly industrial area into a “upmarket waterside playground”. But by 2009, persistent controversy surrounding the lack of diversity and amenity within the area led Lord Mayor Robert Doyle to call for the City of Melbourne to take direct control of its planning, telling the Age it lacked the “social glue” of other suburbs: “At the micro level it doesn’t work. Where would you take your kids to kick the footy? Where would you have a casual beer?”

But avoiding past mistakes is going to be challenging, especially for a project as potentially financially lucrative as Arden-Macaulay, especially when looking at the structures that have given rise to urban renewal, namely that of market-led housing development. A recent MPavilion debate on alternative development financing showed that the removal of a speculative developer reduced the cost of a residential development by 25 to 30 percent, while researchers have pointed to the fact that profit-led apartment developments have the potential to create “vertical slums in the making”.

“There’s no one answer to this, and those answers need to be discussed at multiple levels,” says Bertram. “To do this, we need a multi-scalar approach that the current policy and planning frameworks can’t achieve. The current system is quite fragmented and siloed as each institutional body that overlaps Arden-Macaulay has its own particular focus. What we need is a coordinated planning approach that can roll out and manage a vision-setting agenda, that cuts across current institutional boundaries and interests to look at the long-term gain.”

In the meantime, the final Arden-Macaulay precinct plan is still yet to surface. When contacted for comment, the Victorian Planning Authority said that there were “no definitive proposals or solutions that we would be in a position to explore on record”.

While Bertram’s work, alongside the work of many others, could be dismissed as speculative, urban thinking forged in the fossil-fuel powered fires of the 20th-century city is going to look increasingly outmoded, even dangerous, as the effects of climate change begin to bite.

“Perhaps it’s design’s role to be provocative and in some way provide a vision that other decisions can fit within,” says Bertram. “But public bodies still need to ask: What really is the opportunity here, what could we do, what must we do? What is the legacy we’re going to leave? The ability to think holistically and long-term for this precinct is something that current governance structures can’t achieve. We need different processes that would enable the creation and management of a future-proofed Arden-Macaulay – because the market certainly won’t do it by itself.”

—

Images from ‘Arden Macaulay in Transition’ were produced by MADA Master of Architecture Studio participants, including: Kimberly Atkinson, Timothy Daborn, Alysha Dewar, Christina Erng, Leonor Gausachs, Nathan Gilchrist, David Mason, Emily McBain, Brendan McDowell, Jesse Oehm, Isabella Peppard Clark, Jean-Christophe Olivier Petite, Tai Quach, Matthew Robert Smith, Alexander Williams.