On the Gold Coast, a hidden wall defends against rising seas – will it be enough?

Engineering provides Queensland’s coastal communities with protection from the sea, but if they’re to survive sea level rise, help might be needed in other ways.

It seems as if no article about climate change in Australia is complete without an image of eroding beaches next to Gold Coast skyscrapers – the implication being that the Gold Coast is on the frontline for sea level rise and other effects from global warming. What these pictures don’t show, however, is the A-Line – an almost continuous, five-metre-tall seawall that lies buried under the Gold Coast beaches, built in the late 1960s. The engineers responsible for planning Surfers Paradise coast understood the implications of developing high-rise towers immediately behind the foreshore. These engineers also understood that anchoring what was then a moving sand spit would result in the need for occasional beach renourishment. This prediction has been borne out and Gold Coast beaches, like many popular beaches worldwide, are maintained by a public works program that episodically relocates marine sand from other places onto Gold Coast beaches.

To date, while big storms might occasionally erode the Gold Coast’s beaches, the A-Line has done its job of protecting its ocean-side settlements. That is not to say, however, that the Gold Coast is safe from the threat of sea level rise – somewhat counter-intuitively, much of the danger lies further inland. Like most coastal cities and towns in Australia, the low-lying areas of the Gold Coast have been developed into residential communities. If no adaptation actions are undertaken, some of these low-lying areas will experience nuisance flooding, leading to more problematic inundation as the sea levels continue to rise over coming decades. In response to this increasing threat, there have been many calls to uproot communities and abandon suburbs in favour of relocating them to higher ground. In climate adaptation circles, this is known as the pre-emptive retreat adaptation strategy. To date, there are very few examples of this around the world – presumably because elected officials deem the political risks to be too great. By contrast, there are many examples of communities (or parts of them) being relocated, or prevented from rebuilding, after large natural hazard events – the relocation of Grantham in South-East Queensland, following the 2011 floods, is one example.

In flood-prone properties, risks posed to commercial properties pose threats to a city's overall economy. Image: Kristian Thøgersen

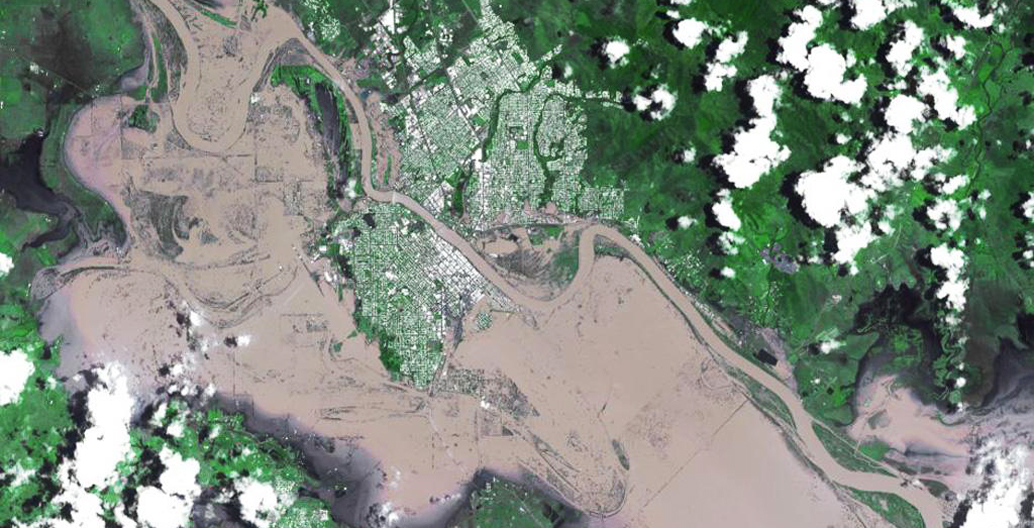

The extent of flooding in 2011 in Rockhampton, QLD. Image: NASA.

To what extent are residents literate in the infrequent, but consequential, risks posed by freak storm events? Image: Tatiana Gerus

This is a drastic solution, but not necessarily the only one. When it comes to combatting the effects of sea level rise, we can learn a lot from the Netherlands. Sixty percent of the Netherlands’ GDP is generated at locations that lie lower than the surrounding sea, so as a nation it is more vulnerable to sea level rise than most. For most of its history, the Netherlands’ has kept the sea out through the construction of a network of dykes and levees. In 2006, in a dramatic change of strategy, the Dutch government embarked on the Room for the River program. A key principle of this program is to change tack from protecting from flooding at all costs, to “living with water”. Under the program, some urban areas will be allowed to flood during major storms, while some roads could become temporary or even permanent waterways as sea levels rise. Water will be in place where water is presently kept out, but rather than a nuisance, it will become a design feature and the built environment will slowly adapt itself to its presence. The key philosophy is to embrace the presence of water, rather than view it as a problem to be kept at bay.

The same opportunity is available to lower-lying parts of the Gold Coast. Over time, rather than simply abandoning whole communities, finer scale adaptation actions can be undertaken. While in some cases individual homes might be lost so that land can be repurposed, this is a far cry from pre-emptively uprooting entire communities.

Regardless of our preferred strategy for coping with sea level rise, there is still a perception in some Australian communities that government should come to the rescue as the insurer of last resort. This is despite clear government guidance to the contrary and a track record of governments not compensating for the loss of private property following major events – apart from token immediate relief funds. For example, the major Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements (NDRAA) scheme in Queensland focuses on public infrastructure. There is also a widespread lack of understanding about the role of private insurers. Insurance companies manage their risk exposure by annualising policies – only insuring for 12 months, and exercising their right to increase premiums. Internationally, a growing number of communities are becoming effectively uninsurable because the vulnerability of their coastal locations places them beyond insurers’ appetite for risk. In Queensland, homeowners in the towns of Roma and Emerald found themselves unable to secure flood insurance after the 2011 floods, until insurance companies successfully lobbied the state government to construct engineered flood protection structures. The flood levees were built, but many have argued that this was a rushed response that creates a moral hazard, by incentivising further development at locations that will ultimately still be at risk.

Low-lying areas within the Gold Coast will be hit severely if adequate adaptation isn't achieved.

To what extent will sea-level rise impact on an Australian property's future capital gains? Image: Aristocrats Hat

Already, storm surges manipulate the central beaches that line the Gold Coast's CBD. Image: CSIRO

Changing community perceptions around the roles of both government and insurers can be tricky. Local governments are now increasingly releasing flood maps showing vulnerable areas, as is the state government in Queensland on a whole-of-state scale. However, waterfront house prices appear to remain largely risk-uninformed, which helps to maintain the buoyancy of the overall property market, but exacerbates the moral hazard. Sea level rise will increase both the intensity and frequency of coastal flooding events and as a result, many families will suffer devastating financial losses. Insurers estimate that at least 23% of houses in Australia are under-insured and other estimates place this figure much higher. There also incentives in the system that embed a laissez faire attitude to climate change risks. For example, insurers generally do not reward homeowners who make their house more resilient with reduced premiums. Similarly, local governments are often, understandably, terrified of any action will lower the market value of private property.

Sea level is rising, and rising at an increasing rate. If all else stays the same, more families will face hardship from flooding. We know which homes will likely be affected – what we don’t know is which families will be left without a chair when the music stops.

Dr Mark Gibbs is a specialist in coastal management, coastal climate adaptation, and risk management and has been providing specialist technical, advisory and Expert Witness services to government and project proponents globally for 25 years. Mark is a non-executive director of Green Cross Australia and a Fellow of the Institution of Engineers Australia . Currently, he is the Director of Knowledge to Innovation at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT).