Rob Adams on the forces reshaping Melbourne for better… and for worse

In this frank conversation, the City of Melbourne’s Director of City Design Rob Adams reflects with Kim Dovey on the legacy of the politicians and planners who have built modern Melbourne, ‘the world’s most liveable city’.

Much has been made of Melbourne’s dramatic revitalisation over the past four decades, of its transformation from dead-eyed industrial town and stubborn redoubt of social conservatism to frothy ‘events city’ with global renown as a centre for all things creative. But while this popular narrative emphasises the alchemical energies of the city’s ‘creative class’ in building the city’s reputation for liveability, it’s often forgotten that much of the responsibility lies not with the artists, designers and laneway impresarios of Melbourne, but with its planners and politicians.

In the following excerpt from a new book charting Melbourne’s dramatic re-birth, Urban Choreography: Central Melbourne 1985–, the City of Melbourne’s Director of City Design Rob Adams and Professor Kim Dovey, Professor of Architecture and Urban Design at the Melbourne School of Design, unpack Adams’ observations from more than three decades working alongside some of Melbourne’s most powerful city-makers.

A detail of the City of Melbourne’s ‘Council House 2’, Australia’s first building

to be awarded a six star green star design rating in 2006. Image: Rob Deutscher.

Kim Dovey: Of Victoria’s planning ministers that have held office since the 1980s, which have had the most important influence in the city?

Rob Adams: There are three that stand out. The first was Evan Walker, who in partnership with the council of the day put in place transformational strategies that were highly successful in turning around many of the negative trends coming out of the modern movement and the dominance of the motor car. Planning controls and projects such as Southbank and Swanston Street were put in place that built on Melbourne’s strengths rather than looking to other cities for solutions. Conservation overlays were put in place, lanes protected, and built-form controls such as plot-ratio limits and setbacks at 30 metres introduced to reflect the height of the traditional city podium. These served the city well until the government changed in 1992 and the new minister, Robert McClelland, in line with his party’s politics, started relaxing controls, particularly in key development areas such as Southbank. More recently, then minister Matthew Guy [now Victorian Opposition Leader] took this approach further by removing the need for setbacks at podium levels that had helped to preserve the amenity at street level as well as retain smaller buildings. Developers of course took this opportunity to increase their yield and during the period of 2010 to 2015 over 60 percent of all planning approvals for residential towers had a plot ratio above 20:1, higher than any other city in a global context.

Arguably one of the most influential politicians was Jeff Kennett. While it was difficult to like all that he did, you had to admire his ability to get things done. He cut through much of the normal hesitancy that new governments have and delivered the greatest number of public projects since the gold rush: a new museum, exhibition centre, Docklands and Federation Square.

This throws up an interesting comparison between the impact of major projects and the incremental delivery of good urban design policies. There can be no doubt about the importance of both, but I believe too much emphasis is often placed on major projects and not enough on good urban policy. Over the thirty years we are looking at, 48 per cent of the central city has been rebuilt. The most influential people over this period have been the statutory planners who on a daily basis direct the development of our city through the instrument of the planning scheme. In the long run, the character of our cities is often set by some very basic rules, such as the 40-metre height limit of the nineteenth century, or the conservation controls and setback requirements of the Walker period. The action that happens at the statutory planner’s desk is the coalface of good planning. If you don’t empower those people to make the right decisions, then incrementally the city is going to get worse; and if you do empower them, then incrementally your city will get better. The planning ministers in Victoria have extraordinary power, and there have been periods when that was not used to the long-term public benefit. In Southbank, the developers were given a relatively free hand and the recommended height limits were often exceeded, by over three times, and setbacks from the street above a certain level often removed or relaxed without any public benefit. What’s the public accountability for that? We’ve got to think carefully about how much power we give to one person, and whether there should be some constraint on that and some measure of the benefit that comes from their decisions.

A detail of the Melbourne Museum, opened in 2000. Image: Rob Deutscher.

A view of the Melbourne Exhibition Centre from the Yarra River.

Federation Square plays host to a range of events and programs. Image: eGuide Travel

Webb Bridge, Docklands. Image: Rob Deutscher.

Southbank in 2017. Image: MUP.

KD When Evan Walker was minister for planning, he put in place a state-led urban design strategy for Southbank, and developers were saying: ‘You can’t be a developer, you’re the minister. You’ve got a conflict of interest’. His response was to set up an Office for Major Projects, at arm’s-length from the Ministry for Planning. What’s your view of that and how that’s played out over the years?

RA I believe it was a good move, allowing the state government to build up the in-house skills to not only deliver a large range of projects but also to be able to deliver meaningful briefs and contracts for government projects. An unfortunate consequence was the demise of the role of the state government architects and Public Works Department, which had until this time been a source of internal intellect that most governments no longer possess. The consequence is that governments have reduced their ability to deliver successful public projects and are no longer intelligent clients. Most governments have contracted out these services, and they have been gone for so long that they no longer recognise them as missing.

KD Urban design, if it’s done well, is a wealth-creating activity. So if the state amalgamates land and then puts it back on the market under a reconfigured framework, they’re likely to make a profit. But what if developers come and say, ‘Hey, that’s our business making profits. You just set the rules’.

RA Claiming the capital gain is exactly what government should be doing. This builds a development fund for government while holding down land prices. The idea that this will hold back development is a myth; developers will factor it into their costs. What has happened in Melbourne in places like Fishermans Bend is that the government has changed the planning scheme to allow increased development rights without putting in place an uplift contribution, thus allowing the land prices to rocket. Landowners, who have made no contribution to planning or development, reap huge windfall profits.

KD Cities are engines of the larger economy, so when cities are working well, economies are working well. This is a point that is becoming realised by political leaders, albeit not as much as we might want. There is also a huge impact that the shape of cities has on energy consumption and climate change. Can you reflect a little on the way in which you see those global governance structures?

RA I think we are at an interesting point in time. In his book If Mayors Ruled the World, Benjamin Barber suggests that with dysfunctional nations, cities offer the best new forms of governance. If cities are to succeed, they have to restructure to meet new social, environmental and economic challenges. Global challenges such as climate change can be engaged locally through projects such as Urban Forests or City as a Catchment. They can be practised at a local individual level and cumulatively help move us towards a sustainable planet. While national governments may be in denial, local action can make a difference.

The other observation I would make is that where national and state governments often compartmentalise their structures into functional silos, such as transport, planning, education, security and health, city governments are more capable of looking horizontally across all portfolios and choreographing more-complex and meaningful solutions.

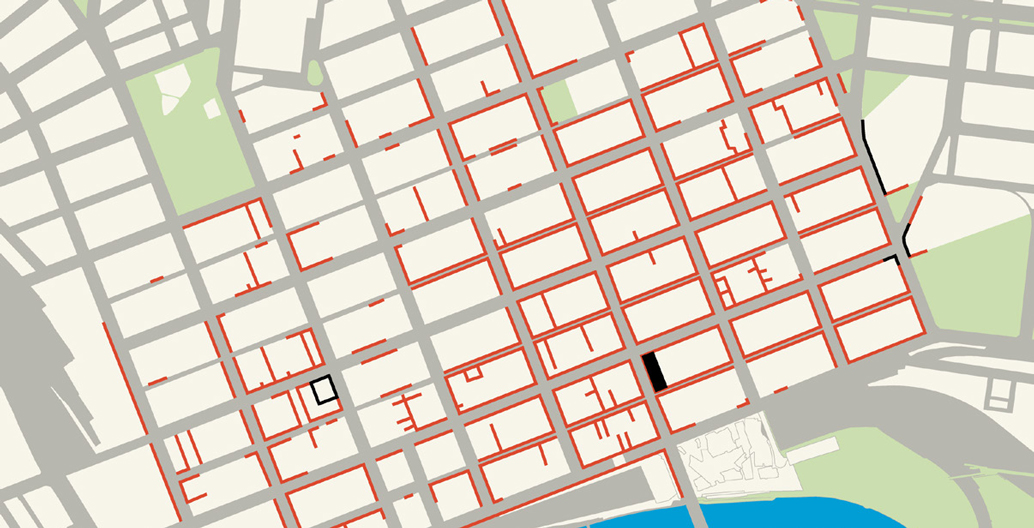

Black = number of bluestone paving in 1985. Red = percentage of paving in 2016.

Sir Roy Grounds’ NGV building has remained a constant since 1968. Image: Gary Sauer-Thompson.

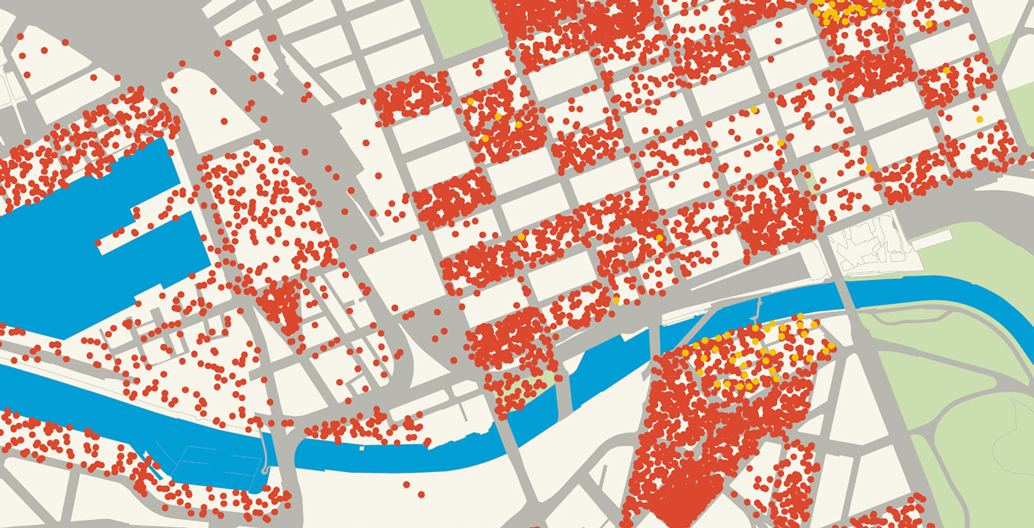

Yellow dots represent the number of CBD dwellings in 1985, compared to the red in 2016.

Melbourne's kerbside cafes in 2016 are marked by red dots, compared to the paltry black ones representing 1985.

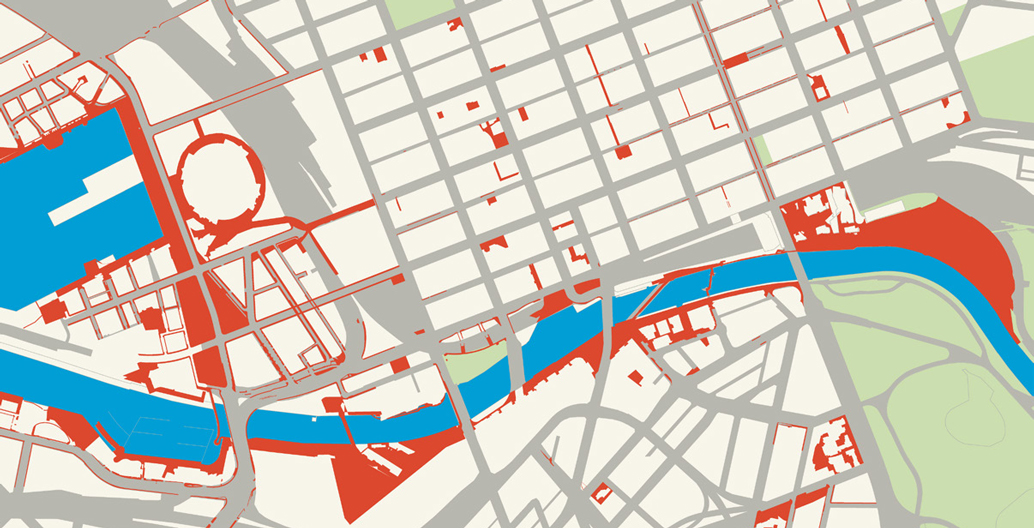

Red markers show the expansion of open pedestrian space since 1985.

KD We have a governance structure which is really a bundle of different forms of governance that are often in tension with each other: federal, local and state, plus different jurisdictions within them that overlap. Should there be a comprehensive urban authority that is in charge of the city?

RA Yes, if we want a coordinated response, then we need a more integrated metropolitan approach. What form this takes is open to discussion, but we need to unbundle the silos to operate in a more coordinated way. Where are the ministers for cities? In their absence, the mayors are the closest to pulling this off.

——

This is an edited extract from Urban Choreography: Central Melbourne 1985– edited by Kim Dovey, Rob Adams and Ronald Jones, out 26 Feb from Melbourne University Publishing. RRP $44.99